Condition of the Roman army. By the end of the 2nd century. BC. The previously invincible Roman army changed greatly. Almost every new war The Romans now began with defeats. The iron Roman legions seemed to have been replaced, and only a few energetic military leaders managed to restore order to their own troops and lead them from victory to victory. But the fact was that the legions were recruited in the old way: only those Roman citizens who had a plot of land. There were fewer and fewer of them: life became more and more expensive, and the Roman peasantry, from which the legions were composed, went bankrupt, lost their land, which was taken over by their rich neighbors - the Roman aristocrats. The soldiers did not want to fight for their interests (namely, in the interests of the rich, Rome now waged wars), and they were increasingly reluctant to join the army. Meanwhile, a mortal danger unexpectedly loomed over Rome and Italy at this time.

Gaul and Germany. North of the Alps and up to Atlantic Ocean The country, which the Romans called Gaul, spread freely. Its eastern border was the Rhine River, beyond which lived tribes of Germans, blond-haired, blue-eyed giants, distinguished by their ferocity in battle and unfamiliar with civilization. The Germanic tribes of the Cimbri and Teutons, who lived in northern Germany, suddenly left their places and moved towards Gaul. Over time, they found themselves close to the borders of the Roman province, which had recently appeared in the south of Gaul.

First clashes with the Germans. They, having heard about the formidable glory of this people, were not going to touch the Romans, but the Roman governor, wanting to become famous for his victory over the barbarians, treacherously attacked them - and was completely defeated. Over the next few years, the Cimbri and Teutones defeated several Roman armies (80 thousand Roman soldiers died in one battle). If after this the Germans had moved to Italy, it would have been doomed. However, instead they moved towards the Pyrenees to invade Spain, and only when they were repulsed by the local tribes did they turn to Italy. All this took them three years, during which the Romans had the opportunity to prepare for the invasion of a formidable enemy.

Guy Mari

Gaius Marius and his innovations. Gaius Mari, who had already become famous in other battles, was elected commander in the war against the Germans. He once served under the famous Scipio Aemilianus, the conqueror of Carthage, and was praised by him for his bravery. Then, already as consul, he victoriously ended the war in North Africa. It was then that Mari decided to recruit into the legions all Roman citizens who wished to serve in them and were fit for health reasons. Marius abolished the previously obligatory condition for recruiting legionnaires - possession of real estate. The difficulties in recruiting the army immediately disappeared: there were a great many willing to serve under the banner of Marius.

For many of the poorest Romans (proletarians), military service became the main source of livelihood, and they began to pin their hopes for their provision after its completion on the commander. A successful and popular military leader could, as soon happened, use the army not only against an external enemy, but also against his political opponents in Rome.

The Maria reform had not only a political, but also a military-technical side. More attention began to be paid to the training of soldiers (political enemies contemptuously called the soldiers of the new army loaded with equipment “Mary’s donkeys”), each legion now received its own banner - a silver eagle on a long pole.

Roman sarcophagus depicting the battle

against the Germans and Celts

Change in combat tactics. But the main thing was that the manipulative tactics of the Romans were replaced by cohort tactics. The Roman manipulative system, which had given them dominance over the peoples of the Mediterranean, proved outdated and ineffective against the dense masses of barbarian infantry, who attacked with unbridled fury and contempt for wounds and death. The throwing weapons of the Romans, including the pilum spear, did not bring the expected effect, because... the first ranks of the Germans turned out to be a reliable shield for the rest. In hand-to-hand combat, the maniple lines were simply crushed by several waves of attackers.

Roman

legionary

eagle

Taking into account the lessons of the defeats, Mari, instead of the maniple, made the cohort the main tactical unit in the Roman army. Cohort formation was not a Roman invention, they borrowed it from their Italian allies. The cohort consisted of 500-600 people, and its formation was distinguished by greater depth than that of the maniple of 60-120 people. The previous division of warriors into hastati, principes and triarii was abolished; legionnaires now served in the cohort different ages, so that the combat capabilities of each tactical unit were approximately the same.

The legion was still formed before the battle in three lines, and the cohorts, as before the maniples, stood in a checkerboard order: four cohorts of the first line, three of the second and three of the third. In total, the legion numbered ten cohorts; it was now given so-called auxiliary troops from among the provincials and peoples dependent on Rome, both cavalry and infantry.

The Roman cavalry itself ceased to exist, the legion became a purely infantry formation, which, in addition to heavy infantry, included engineering units, reconnaissance and convoys.

Centurions. Centurions (60 per legion) still commanded centuries and maniples. Depending on their merits and length of service, they advanced within the legion along the “career ladder” to the position of primipile (“first spear”) - the senior centurion of the legion; that's it for them military career ended because officer positions were occupied by aristocrats.

Officers. These were military tribunes from the equestrian and senatorial classes, six people per legion. They formed the headquarters of the military leader and had to carry out his orders, both one-time and permanent, for example, taking command of a cohort or even a legion. However, usually the legion was now commanded by a legate, who was appointed by the military commander. The post of legate was required because the number of legions had increased significantly and the military leader himself (with the rank of consul or praetor) could not directly command each legion.

Units of auxiliary troops (infantry or cavalry cohorts, cavalry troops) were commanded by prefects, either from among the Romans, or (in rare cases) from representatives of provincials or barbarians, who received Roman citizenship for special merits.

The meaning of reform. This structure of Roman ground forces proved its effectiveness not only at the end of the Republic, but also in the first centuries of the Empire. The Romans' cohort tactics allowed them not only to repel the invasion of the Germanic tribes of the Cimbri and Teutons, literally wiping them off the face of the earth, but also to conquer vast territories in Western and Central Europe. In the East, they managed to defeat their last formidable enemy from among the Hellenistic rulers, the famous Mithridates VI Eupator.

Gaius Marius, “savior of the fatherland,” was elected consul seven times, defeated Jugurtha, the Cimbri and the Teutones. In addition to being a talented commander, Marius was also a capable military organizer. It is Gaius Marius who is credited with numerous reforms of the Roman army. Let's take a closer look at exactly what reforms Mari carried out.

Plutarch, “Comparative Lives”

“Courageous by nature, warlike, brought up more as a soldier than as a peaceful citizen, Marius, having come to power, did not know how to tame his anger... He began his military service in Celtiberia, where Scipio Africanus (Emilian) was besieging Numantia. It did not escape the commander that Mari surpassed other young men in courage and easily endured the change in lifestyle to which Scipio forced the soldiers spoiled by luxury and pleasure. They say that in front of the commander’s eyes he defeated the enemy, with whom he came face to face. Scipio distinguished him noticeably, and once, when at a feast the conversation came up about generals and one of those present, either in reality, or wanting to say something nice to Scipio, asked if the Roman people would ever again have someone like him , leader and protector, Scipio, clapping Marius lying next to him on the shoulder, replied: “It will be, and maybe even he.” Both of them were so richly gifted by nature that Mari, even in at a young age seemed an extraordinary man, and Scipio, seeing the beginning, could predict the end... While serving as praetor, he did not win himself any special praise, and at the end of his term he received Outer Spain by lot, which, as they say, he cleared of robbers... Consul Caecilius Metellus, who was entrusted with command, going to Africa, took Maria with him as a legate.”

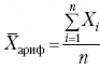

Selected in 107 BC Consul Gaius Marius begins reforms in the army.

- He drafted proletarians into the army.

Sallust Crispus, Jugurthine War, 84.86

Reforms Maria

“...However, he (Marius) attached special importance to preparations for war: he demanded replenishment for the legions, attracted auxiliary units recruited from peoples, kings and allies; in addition, he summoned all the bravest soldiers from Latium, most of whom he knew from campaigns, and some from their good reputation; meeting with those who had served their time (veterans, the so-called evocati, soldiers whom the commander took for extended service with their consent.), he persuaded them to leave with him...

In the meantime, he himself recruits soldiers, but not according to the custom of his ancestors and not according to ranks, but anyone who wishes, for the most part personally included in the lists. Some explained this by the lack of decent citizens, others - by the ambition of the consul, for it was these people who glorified and elevated him, and for a person striving for dominance, the most suitable people- the most needy, who do not value property, because they have nothing, and everything that brings them income seems honest to them.”

Artist Johnny Shumate

Aulus Gellius, Attic Nights, 10/16/9

Reforms Maria

“Those who were the most insignificant and poor of the Roman people, and who brought no more than one thousand five hundred copper asses to the census, were called proletarians, while those whose property was valued in even less copper, or who had nothing, were called capite censi (recorded in person) , and the maximum qualification for “personally rewritten” was three hundred and seventy-five copper asses. But, since the state and property of the family were considered by the state to be a guarantee and pledge of love for the motherland, neither proletarians nor those “personally enlisted” were enlisted in the army, except in cases of the greatest revolts, because their fortune and property was small or completely insignificant. However, to be a proletarian, both in name and in fact, was much more honorable than being “rewritten in person”: after all, in difficult times for the state, when there was a need for combat-ready young men, they were recruited into a hastily created army and provided with weapons at the expense of the state, and they were called not on the basis of a universal qualification, but more respectfully - according to their duty and duty to produce offspring (proles), since, although they could help the state less with their fortune, they increased the power of the community by giving birth to children. And the “personally rewritten” were first recruited into the army, as some say, by Gaius Marius during the war with the Cimbri in the most difficult time for the republic, or rather, as Sallust reports, during the Jugurthine War, which had never happened before in anyone’s memory.”

As you can see, there are some discrepancies in the primary sources between the proletarians and those “rewritten personally.” However, it is clear that Mari did not refuse anyone and took everyone - both evocati veterans who had served their time and those who previously could never be enlisted in the army due to their status. These latter were no longer fighting for their property, which they did not have, but for their commander, who could divide the spoils obtained in battles among the soldiers. Forced recruitment into the Roman army was not abolished. When there were not enough volunteers or it was necessary to make up for serious losses (the Battle of the Teutoburg Forest), forced recruitment of soldiers was still carried out.

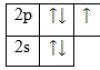

- Abolition of the division of conscripted soldiers into hastati, principes and triarii. Abolition of the hasta, arming all legionnaires with pilums. Replacement of velites and horsemen with allied contingents.

This is not explicitly stated in the primary sources. Most likely, this is attributed to Marius based on logical deductions. If the rank and age during recruitment are not respected, and the poor are armed at state expense, then most likely the legionnaire becomes a generalist. The poorest volunteers go to the legions. There is no point in making them velites when javelin throwers can be recruited without problems from other nationalities. Instead of velites, during the time of Caesar, legionnaires with lightweight weapons were used - antesignans.

The same applies to cavalry. Aristocrats at the commander's headquarters could form small cavalry detachments. And the basis of the cavalry, much best quality, than the Roman one, were allies or mercenaries. However, even during the Jugurthine War, Sallust points to the cavalry of the Romans and Italics: “95. (1) Meanwhile, the quaestor Lucius Sulla arrived at the camp with a large cavalry recruited from Latium and from among the allies, for which purpose he was left in Rome.”

Artist Angus McBride

Gasta could have disappeared from the armament of the triarii even before the reform of Marius. For the second half of the 2nd century. BC. I haven't seen it mentioned. But what Marius really did in the field of weapons was to improve the pilum. As Plutarch writes about: “It is believed that it was in this battle that Marius first introduced innovation in the design of the spear. Previously, the tip was attached to the shaft with two iron spikes, and Marius, leaving one of them in the same place, ordered the other to be removed and a brittle one inserted in its place. wooden nail. Thanks to this, the spear, when it hit the enemy’s shield, did not remain straight: the wooden nail broke, the iron nail bent, the bent tip simply got stuck in the shield, and the shaft dragged along the ground.”

- Changing the legion's manipulative tactics to cohort tactics.

In various popularization books with beautiful diagrams of a manipular legion with centuries of 60 people (triarii of 30 people) and with cohorts of Maria of 6 centuries of 80 people, this statement is considered self-sufficient. There is no such thing in the primary sources. The transition from manipular tactics to cohort tactics is attributed to Marius (before the Battle of Vercelli), just as the transition from phalanx to maniples is attributed in one version to Camillus.

First of all, in Polybius’s legion the centuries could have been not 60, but 80 people each, if the legion consisted of not 4200, but 5000 or more soldiers. Polybius, General history, 6.20-24 “When the required number of soldiers is selected, it is determined to be four thousand two hundred infantry, or five thousand if more are expected difficult war… If the number of soldiers exceeds four thousand, the distribution of soldiers by rank will change accordingly, with the exception of the triarii, whose number always remains unchanged.”

And before Marius, the Italic allies fought in cohorts. Titus Livius, 25.14 “The signal to retreat was already sounded; but these plans of the commander were ruined by the soldiers, who rejected such a cowardly order with a disdainful cry. The closest to the enemy was a cohort of Peligni; its prefect Vibius Akkai grabbed the banner and threw it over the enemy rampart: “Cursed be I and my cohort together with me if the enemy takes possession of this banner.” He jumped over the ditch and burst into the camp. The Peligni were already fighting in the enemy camp, and Valerius Flaccus, military tribune of the third legion, reproached the Romans for cowardice: they were inferior to the allies in the honor of taking the camp. Titus Pedanius, the first centurion, snatched the banner from the standard bearer: “This banner and this centurion will be in the enemy camp; whoever does not want the enemy to take possession of the banner, follow me.” He crossed the ditch first, followed by his maniple, then the whole legion.” Cohorts of Peligni and Marucins were the first to rush at the enemy in .

True, we do not know either the weapons or the tactics within the Allied cohorts. It is logical to assume that the allied cohorts could not be armed and fight differently than the Romans. This would be difficult for joint action. Cohorts appear in the texts of primary sources also in Spain, in. Livy describes the maneuver of the army of Scipio Africanus: “Having thus stretched the flanks, their commanders quickly moved towards the enemy - each at the head of three infantry cohorts, three detachments of cavalry and - in addition - spearmen (javelin throwers); the rest of the army followed them obliquely.” Option of Polybius: “He (Scipio) himself separated from the left wing, and Lucius Marcius and Marcus Junius from the right three advanced turmas, in front of them, according to the custom of the Romans, he placed lightly armed and three maniples, which is what the Romans call an infantry detachment cohort, - with his army he made a turn to the left, and Lucius and Mark to the right, and the column moved at an accelerated pace towards the enemy ... "

It can sometimes be difficult to determine whether the term “cohort” refers to the Italics or whether the later author is using contemporary terminology. In the Jugurthine War, Salustius can find a description using both maniples and cohorts: 49.6 “Having changed the battle formation, on the right flank, closest to the enemy, he installed warriors in three lines, including a reserve, placed slingers and archers between the maniples, and all the cavalry placed on the flanks and, without wasting time, saying only a few words to encourage the soldiers, in the same order that he had given them, turning the front ranks to the left, he led them to the plain.” 51.3 “Finally, when everyone was already exhausted from hardship and heat, Metellus, seeing that the onslaught of the Numidians was weakening, gradually gathered the soldiers together, restored the battle formation and placed four cohorts of legionnaires (Romans???) against the enemy infantry.” 56.4 “He (Jugurtha) goes there at night with selected cavalry and, when the Romans were already leaving the city, starts a battle at the city gates; at the same time, with a loud cry, he calls on the inhabitants of Sikka to attack the cohorts (Roman???) from the rear.” Velius Paterculus, “Roman History”, 5: “Even before the destruction of Numantia, a brilliant campaign of D. Brutus took place in Spain, who, having bypassed all the peoples of Spain and captured a huge number of people and cities, reaching those that hardly anyone had heard of, earned the name Gallekus. A few years before him, among the same peoples, the famous Kv. The Macedonian commanded the army so harshly that during the siege of the Spanish city of Contrebia he ordered five cohorts of legionnaires to immediately recapture the fortified position from which they had been driven out.”

Quite definite indications of cohorts appear a little later than the supposed reform of Marius during the time of Vercellus. The times of the Allied War with the Italics and the civil war of Sulla with the Marians, as well as the war of Sulla with Mithridates. For example, Appian, Civil Wars, 1.87 “The next year (82 BC) Papirius Carbo became consuls for the second time and Marius, who was only 27 years old, nephew of the famous Marius ... Sulla captured Setium, after which Marius, who encamped near him, moved back a little. Arriving at the so-called sacred harbor, he lined up his army in battle formation and fought bravely. When the left flank began to give up its positions, five cohorts of infantry and two turmae (still Roman-Italian cavalry???) cavalry could not resist and gave the signal to retreat, abandoned their banners and transferred to Sulla’s side.” As a result of the Allied War, the Italics received Roman citizenship and began to serve in the legions, rather than in individual allied cohorts. It is likely that from this point on the cohort became the main tactical unit. However, all the beautiful diagrams with the location of cohorts on the battlefield date back to the time of Caesar.

Caesar, Civil Wars, 1.83 “Aphranius formed two battle lines out of five legions, and the third, as a reserve, was occupied by auxiliary cohorts. Caesar's front also consisted of three lines, but in the first line there were four cohorts from his five legions, followed by three as a reserve, and then again also by three cohorts from the corresponding legions; The archers and slingers stood in the center, the cavalry covered the flanks.”

- "Marie's Mules"

Plutarch, Comparative Lives, Mari: “On the campaign, Mari tempered the army, forcing the soldiers to run a lot, make long marches, cook food and carry their luggage, and from then on, hardworking people who meekly and willingly carried out all orders began to be called “ Marie's mules." True, many point out that this saying arose under different circumstances. Scipio, besieging Numantia, decided to check how his soldiers put in order and prepared not only their weapons and horses, but also their carts and mules. Then Marius brought out a well-fed horse and a mule, which surpassed everyone else in strength, strength and obedient disposition. The commander liked the animals so much that he often thought about them, and therefore, when they want to jokingly praise a person for his perseverance, endurance and hard work, he is called “Mary’s mule.”

And before Marius, many generals, seeing the army in a disassembled state, restored order to it. In particular, under the same Numantia, Scipio Aemilianus, 134 BC, raised discipline with harsh measures, abandoned the convoy and forced the soldiers to carry everything on themselves. Livy reports this in the period to book 57: “He sold all the pack animals so that the soldiers themselves could carry the luggage.”

- Marius, according to Pliny the Elder, replaced the old badges of the legions (signa), which were images of animals - a wolf, a minotaur, a horse, a boar, a bull - with a silver eagle (aquilae). Later, eagles began to be made of gold.

So, the Roman army changed significantly from the time of Polybius to the time of Caesar. Some changes are clearly associated with the name Maria, while other changes could have occurred gradually and are simply attributed to Maria as a talented commander and reformer of the Roman army.

Military reforms Maria is a kind of axiom, which, as a rule, is easily taken on faith by people who have begun to be interested in the history of Ancient Rome. However, upon closer examination, it turns out that the qualitative changes and reorganization in the Roman army of that time are completely wrongly attributed to one person.

Maria's well-known reforms that never happened

During discussions at military-historical forums, the author repeatedly had to deal with participants’ appeal to the “Maria reform.” The same concept is present in popular and even specialized literature, and authors do not always take the trouble to explain its content. Both among amateur historians and among professionals, the prevailing attitude is towards the “Marian reform” as a well-known fact that does not require special evidence. In fact, military reform associated with the name Maria is an artificial concept that unites phenomena and processes that have developed over a long period of time and often without any connection with the name of this military leader and politician.

Alleged image of Gaius Marius from the collection of the Antique Collection, Munich

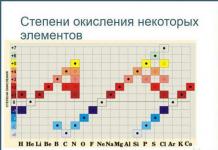

The broad historical public associates the “reforms of Marius” with the initial stage of professionalization of the Roman army. Personal credit for this process is usually attributed to Marius himself, who acts as the creator of a new type of army. Among the military innovations he implemented, the following are usually listed:

- transition to recruiting the army from low-income strata of the proletariat;

- organization of permanent legions stationed on the territory of the conquered provinces;

- changes in organizational structure legions, abolition of the previous division into maniples, introduction of cohorts as new staff units; the disappearance of the division of legionnaires into hastati, principes and triarii;

- introduction of a uniform supply of soldiers. Let us analyze each of the listed reforms for their compliance with the activities of Maria.

1. Acquisition

Of all the “Maria reforms,” the transition to the military recruitment of proletarians has the most important consequences. Information about the recruitment of the poor undertaken by Marius is based on direct instructions from Sallust (Sall. Jug., 86, 2), Gellius (Gell., XVI, 10, 14), Plutarch (Plut. Mar., 9), Valerius Maximus (Val. Max. II, 3, 1), Flora (Flor., I, 36, 13). Sallust and Plutarch date this event to the first consulate of Marius in 107, although Gellius accepts the same date, but mentions a tradition that dates this event to 105. To find out what measures Marius carried out, for what reasons and with what consequences, one should briefly discuss the rules of recruitment into the Roman army.

According to the constitution of Servius Tullius, the Roman people were divided into five property categories, each of which fielded a certain number of soldiers. Beyond five digits (according to the expression of the sources “ infra classem» ) there were poor citizens who did not have sufficient wealth to purchase weapons on their own. Livy reports that the proletarians included those whose property was valued at less than 11,000 asses, i.e. the minimum level for the fifth property category. The proletarians were called up only when a state of emergency was declared: during the war with Pyrrhus in 281 BC, (Gell., XVI, 10, 1; Oros., IV, 1, 3; Aug., De civ. Dei, III, 17), after the defeat at Lake Trasimene and at Cannae (Liv., XXII, 11, 8; XXII, 59). Under ordinary circumstances they served in the navy (Liv., XXII, 11, 8; Polyb., VI, 19, 3). This situation remained until II Punic War.

Polybius, describing the Roman army around 160 BC, reports that the minimum property qualification for service in the army is the amount of 4000 Roman aces (Polyb., VI, 19, 2). This amount is 2.5 times lower than that indicated by Livy. Researchers consider the discrepancy in figures to be the result of lowering the property level for citizens liable for military service of the V category. E. Gabba proposed to date this event to the beginning of the Second Punic War. He pointed to Livy's data on the conscription of proletarians for military service in 217 and 214 BC. and the unexpected absence of these data for subsequent times. Livy reports the conscription of freedmen and the liberation of slaves, but says nothing about the Roman proletarians. This silence is explained by the lowering of the property level for military recruitment, which allowed the Senate to recruit the top of the proletariat without declaring a state of emergency. Most likely, the proletarians served as lightly armed velites, who first appeared in the Campanian theater of war in 212 (Val. Max. II, 3, 3).

Conducting a census on the relief frieze of the altar of Domitius Ahenobarbus of the 2nd–1st centuries. BC. On the left side of the image, a citizen, under oath, provides the censor with information about his family members and property belonging to him. Louvre, Paris

Conducting a census on the relief frieze of the altar of Domitius Ahenobarbus of the 2nd–1st centuries. BC. On the left side of the image, a citizen, under oath, provides the censor with information about his family members and property belonging to him. Louvre, Paris

The amount of 4,000 asses is also not final. Cicero in the middle of the 1st century. BC. states that the border between citizens of the fifth property class and the proletarians runs at the amount of 1500 asses (Cic. De Rep., II, 40; Gell., XVI, 10, 10) 3). Although Cicero attributes this state of affairs to the era of Servius Tullius, it is obvious that the reduction in the qualification amount of 4,000 Roman asses indicated by Polybius occurred only in the second half of the 2nd century. BC. It is extremely tempting to connect this event with the actions of Marius, but the most common hypothesis at the moment is another hypothesis. E. Gabba proposed to date this event to 123 and connect it with the military legislation of Gaius Gracchus. The attraction of proletarians to military service was supplemented by laws on arming recruits at state expense and on the minimum conscription age of 17 years, which was supposed to protect new class persons liable for military service from abuse (Plut. Grach., 26, 5). In 109, some of these laws were repealed (Asc. In Corn. P.54, 25), but the lower level of conscription remained at 1,500 asses.

This assumption seems convincing and deserves more confidence than the hypothesis that attributes the authorship of this innovation to Marius. All sources at our disposal note the unusual nature of the recruitment undertaken by Marius. First of all, let us make a reservation that neither in 107, nor two years later, Marius recruited a new army. He received command of the active army, recruited in the first case by Metellus, in the second case by Rutilius Rufus. Marius recruited only the reinforcements necessary to make up for his losses. Their number for an army of two legions hardly exceeded 3,000 people. The Senate, according to Sallust, willingly gave the consul the opportunity to carry out the recruitment, secretly hoping that this unpopular measure would weaken his authority among the common people. Marius, having realized this plan, did not resort to the usual recruitment and recruited volunteers from among the lower social classes. Thus, he retained the support of the people and received the necessary reinforcements (Sall. Jug., 86). It should be noted that Mari did not create a historical precedent with his actions. Other Roman military leaders who were in difficult relations with the Senate had previously acted similarly (App. Iber., 38).

2. Organization of permanent legions stationed in the conquered provinces

The main part of the Roman army was the legion. In the VI–III centuries. BC. legions were usually created for one campaign and included warriors of the same set. At the end of the summer campaign, the legion was disbanded and recruited again in the spring. Under normal circumstances, the army consisted of four legions, commanded by two consuls. If it was necessary to wage long wars, the old legions were not disbanded, but recruits spring conscription formed additional legions. Thus, during the Second Punic War, the Roman army consisted of 28 legions. After 200 BC it usually consisted of 8 legions, sometimes less, sometimes more. As the number of provinces increased, the number of legions increased. From 2 to 4 legions were constantly stationed in Spain, 2 in Cisalpine Gaul, 2 in Macedonia and Illyria. At the beginning of the 1st century. BC. Africa, Cilicia, Bithynia were added to the number of provinces, and the number of legions stationed on their territory reached 14.

The only difference between this practice and that used during the imperial era was the length of military service of the soldiers. Although any Roman citizen was obliged to serve in the army for 20 years (Polyb., VI, 19, 4), in reality the period of military service was usually a maximum of 4–6 years, after which soldiers of the old conscription were demobilized and replaced by new recruits. Volunteers who chose a career as professional soldiers served longer than others. A famous example is Spurius Ligustinus, who by the time he reached the age of 50 had served 22 years as a soldier and centurion (Liv., XLII, 34). With the growing militarism of the Roman Republic, the number of veterans in the army increased. If at the beginning of the 2nd century. BC. While military service covered approximately a third of the adult population of the Republic, by the middle of the next century half of the men were already serving.

Roman warriors of the 2nd–1st centuries. BC. on the relief of the altar of Domitius Ahenobarbus. They wear a bronze helmet with a horsehair plume, are dressed in chain mail and hold a large oblong shield. Louvre, Paris

Roman warriors of the 2nd–1st centuries. BC. on the relief of the altar of Domitius Ahenobarbus. They wear a bronze helmet with a horsehair plume, are dressed in chain mail and hold a large oblong shield. Louvre, Paris

Thus, in the Roman army during the 2nd–1st centuries. BC. there was a clear trend towards professionalization. The legions gradually turned into permanent combat units; warriors, most of whom had experience in military campaigns, served in their ranks. This process was complex and systemic in nature and was in no way the result of the activities of one person.

3. Changes in the organizational structure of the legions

Contrary to popular belief, cohorts in the Roman army appeared long before Marius. The word "cohort" has ancient origin and may be related to the method of recruiting troops practiced by the Italics. The cohort is repeatedly mentioned as an element of the system of both the Italian opponents of Rome (Liv., II, 14, 3; X, 40, 6), and the Romans themselves (Liv., II, 11, 8; IV, 27, 10). Analysis of this term shows that in the sources it means separate units, selected from the mass of troops to solve a special task. Cohorts in Scipio's Spanish army, as a rule, included 3 maniples of infantry, 3 cavalry and lightly armed velites (Polyb., XI, 21, 1; 33, 1). At the same time, the cohort remained a temporary formation, disbanding upon completion of the task assigned to it. Of particular note is that the cohorts of that period did not have their own commander and banner.

Warriors of the Spanish auxiliary cohorts of the 1st century. BC. Reliefs from Monument A of Osuna

Warriors of the Spanish auxiliary cohorts of the 1st century. BC. Reliefs from Monument A of Osuna

The main combat unit of the Roman army was the century. Each century had its own commander and its own banner. By centuries, the Roman army lined up on the battlefield, settled in a camp, and received equipment and food. The maniple was a union of two centuries. The maniple was commanded by a senior centurion; the maniple had a special role in the battle formation. A similar order, which developed back in the era of the classical Republic, remained until the end of antiquity. The idea of Marius abolishing the manipular order and replacing it with cohort-based construction does not stand up to criticism. On the one hand, how written texts, and epigraphic sources indicate the preservation of the division into maniples and centuries during the 1st century. BC. – III century AD The same data indicate the preservation of the previous names of hastati, principles, triarii (Caes. BC., I, 41; 44; Afr., 83). On the other hand, no tactical changes occurred at this time either, because On the battlefield, the troops, as before, continued to line up in centuries.

4. Introduction of uniform supply of soldiers

The Roman warrior of the Republic era had to arm himself for service. His equipment had to correspond to the property qualification. Wealthy citizens served in the heavy infantry and were armed full armor, sword and shield, the poor wore incomplete armor or fought in light infantry. During annual reviews, officials ensured that the recruit did not skimp on military equipment. If necessary, weapons were provided to the warrior by the state, the cost of the equipment was then deducted from the salary (Pol., VI., 39, 15). Responsibilities for paying the cost of weapons fell heavily on the shoulders of poor recruits. In 123, Guy Gracchus tried to pass a law according to which the supply of weapons to soldiers was carried out at state expense (Plut. Grach., 26, 5). However, this law was soon repealed, since the system of deductions from salaries for the cost of soldiers' equipment was a common practice of the Principate era (Tac. Ann., I, 17, 6).

The increase in the size of the Roman army and the gradual deterioration in the well-being of recruits increasingly forced the state to take on the function of providing soldiers with ready-made batches of weapons and armor. Around 102 BC the Arsenal is being built in Rome (Cic., Pro Rab., 20). There is a concentration of military production, and the products of gunsmiths are significantly standardized, which is demonstrated archaeological finds this time. These processes have completely transformed appearance soldier. If in the armies of Marius and Sulla we still find Roman velites recruited from among the poorest conscript classes, then fifty years later, in the army of Caesar, the functions of light infantry and cavalry were completely carried out by the allied troops. Legionnaires constituted the only category of heavily armed infantry.

Caricature of Roman soldiers on a Pompeian fresco of the 1st century. AD with the scene of Solomon's judgment. National Museum of Rome

Caricature of Roman soldiers on a Pompeian fresco of the 1st century. AD with the scene of Solomon's judgment. National Museum of Rome

With the expansion of expansion and an increase in the size of the army in the Roman Republic, processes arise that are artificially combined by historians into the “Reform of Marius.” These processes include expanding the class of Roman citizens liable for military service by lowering the property qualification level and conscripting the poor for military service ca. 212 and again ok. 123 BC. Continuous military operations on the territory of the provinces lead to an increase in the service life of citizens; the legions actually turn into permanent garrisons located on the border in readiness to repel an enemy attack. The percentage of professional soldiers in their ranks is constantly increasing. The state actually takes into its own hands the function of supplying recruits with weapons and military equipment. Although Mariy played significant role in the development of these processes, he himself did not carry out active reforms capable of speeding up or weakening their progress. Therefore, they should hardly be directly related to his name.

Literature:

- Makhlayuk, A. Roman wars / A. Makhlayuk - M.: Tsentrpoligraf, 2003 - P. 247; 263–271.

- Gabba, E. Republican Rome, the army, and the allies / E. Gabba - Los Angeles: California Press, 1976 - P. 5.

- Gabba, E. Republican Rome, the army, and the allies / E. Gabba - Los Angeles: California Press, 1976 - P. 7.

- Brunt, P. A. Italian manpower, 225 B.C.-A.D. 14 / P. A. Brunt - Oxford: University Press, P. 426–435. Smith, R. E. Service in the post Marian Army / R. E. Smith - Manchester: University Press, I958 - P. 11–26.

- Tokmakov, V. N. Military organization Rome of the Early Republic (VI - IV centuries BC) / V. N. Tokmakov - M.: RAS, 1998 - p. 216–217

Maria's military service began in Spain under the command of Scipio Aemilianus during the war with Numantia. In 119 BC. Marius achieved the position of tribune of the people in Rome and passed a number of laws in favor of the plebs. He was then elected praetor and given control of Outer Spain. Marius strengthened his position in Rome by marrying an aristocrat from the Julian family, the aunt of Julius Caesar.

As a legate under the commander Caecilius Metella, Marius took part in the war with the Numidian king Jugurtha. In 108 BC. e. he left North Africa and sailed to Rome to stand as a candidate for the consular elections. Mari turned to the Roman people with a promise to successfully end the war and capture Jugurtha, alive or dead. Elected consul, Mari carried out a military reform, which was destined to have a decisive influence on the fate of republican Rome. He abolished the property qualification for recruitment into the army, thereby taking the first step towards transforming people's militia fellow citizens into a mercenary army. The soldiers in Maria's army received their salaries and full equipment at the expense of the state; their service life lasted 16 years and did not depend on whether there was a war going on at that time. Mari strengthened military discipline: soldiers had to constantly undergo training, work in the camp, build roads and fortification lines. Professional warriors were popularly nicknamed “Mary’s mules,” which emphasized the change in the relationship between the commander and the army. Entirely dependent on the military leader, the soldiers sought new campaigns that promised them military spoils; under his command they were ready to act not only against an external enemy, but also against their fellow citizens. Marius said that the consulate was a trophy that he took in battle from the pampered Roman nobility: after all, he could only boast to the people of his own wounds, and not a series of images of dead ancestors.

Marius fulfilled his promise to end the war in North Africa with victory and celebrated this event triumphantly on January 1, 104 BC. However, it was not he who captured King Jugurtha himself, but the young aristocrat Lucius Cornelius Sulla. The ambitious Marius did not want to share his glory as a winner with anyone. Plutarch pointed out that this enmity, “so insignificant and childishly petty in its origins, led through bloody strife and severe unrest to tyranny and the complete breakdown of affairs in the state.”

In 104 BC. Mari was entrusted with the fight against the Germanic tribes advancing on Northern Italy. He was elected consul and, contrary to custom, retained supreme power for five years (104-100 BC). In 102 BC. At Aqua Sextius, Mari defeated the Teutons, in the next 101 BC. defeated the Cimbri at the Battle of Vercellae. “The common people called him the third founder of the city; at a festive meal with his wife and children, everyone dedicated the firstfruits of food and poured libations to Mary along with the gods” (Plutarch).

Early 1st century BC was marked in Rome by clashes between the optimates, supporters of the old Senate aristocracy, and the populares, who sought support from the plebs. Wanting to earn recognition from the Senate, Mari in 100 BC. suppressed the speech of Lucius Saturninus, who advocated the provision of land plots to veterans. Nevertheless, the Senate did not change its half-contemptuous attitude towards Marius.

In the early 80s BC. e. Rome was preparing for war with the Pontic king Mithridates VI Eupator. It was obvious that whoever led the army against Mithridates would be guaranteed the support of the army and rich conquests in the East. The struggle for consular power brought victory to Marius's longtime rival Lucius Cornelius Sulla. Marius managed, relying on all the opponents of the Senate, to achieve a change of command. Sulla's army decided that the newly appointed commander would recruit a new army, and demanded reprisals against Marius' supporters. For the first time in the history of Rome, the city was taken by its own army, Marius’s allies scattered, and he and his son were forced to go into hiding.

When Sulla left Italy with his army and went on a campaign to the East, Mari recruited his army and besieged Rome. He was supported by one of the consuls of 87 BC. Lucius Cornelius Cinna; another consul, Gnaeus Octavius, was a supporter of Sulla and led the defense of the city. Unable to bear the hardships of the siege, the inhabitants of Rome rebelled and killed Octavius. The Senate sent envoys to Marius and Cinna with a request to spare their fellow citizens, to which Marius replied that the law prohibited him, an exile, from entering the city. The National Assembly barely had time to rescind its decision to expel Marius when his troops entered Rome. Maria's bodyguards killed everyone he pointed at. “Every day, Marius, increasingly inflamed with anger and thirst for blood, attacked everyone against whom he harbored at least the slightest suspicion. All the streets, the whole city, were swarming with pursuers hunting for those who were running away or hiding” (Plutarch). Marius and Cinna were elected consuls for the year 86. This last, seventh consulate, which seventy-year-old Mari received, lasted only 17 days. He died unable to withstand the tension of the struggle for power.

Guy Mari

The commander, for the first time in the history of Rome, was elected consul for four years in a row

Guy Mari

At the very end of the 2nd century BC. e. Rome had to deal with the Germanic tribes of the Cimbri and related Teutons, who migrated from the north through modern Switzerland to the south of Gaul. The newcomers turned out to be warlike and in 109 BC. e. in a clash with the Roman army of Junius Silanus, they defeated him on the banks of the Rodan River. After this, the “barbarians” established themselves in Northern Italy.

In 107 BC. e. The Cimbri and Teutones defeated the consul Cassius Longinus. In 105 BC. e. The “barbarians”, led by their leader Boyorix, celebrated the victory at Arauosin (modern Orange) on the left bank of the Rodan River. Here two consular armies were completely defeated, that is, exterminated.

A terrible bloodshed occurred: the Romans lost 80 thousand legionnaires in one day. Only ten people were saved, who managed to escape from the battlefield and swim across the river. After this, the victors also destroyed 40 thousand Roman “non-combatants” who did not participate in the battle, being in the army’s rear.

Panic began to spread in Rome. After such a terrible defeat military force the imminent arrival of the “barbarians” under the walls of the Eternal City was expected.

A strong general was needed, and for the first time in the history of Ancient Rome, a man remained consul for four years in a row. This was Gaius Marius, the most popular person among the Roman plebs, experienced in military affairs, decisive and consistent in his actions.

Before continuing the war with the Cimbri and Teutones, Gaius Marius reformed the army of Rome. If previously only those citizens who owned land were accepted into it, now everyone who was fit for the job was accepted. military service. Those recruited as legionnaires were obliged to serve for at least 16 years, after which they received the right to be allocated land. During their service, legionnaires received government allowances and salaries.

In addition, Gaius Marius swore to share the spoils of war with his soldiers. And it has always been attractive to legionnaires, who could get rich and build their own well-being in one successful campaign.

As a result of the military reforms of Gaius Maria, the Roman Republic received a large army that was professional, well trained and seasoned in wars and campaigns. Its feature in the near future became devotion to a successful or popular commander. This is how a major political force appeared in Ancient Rome in the form of its own army.

Gaius Marius, having set out at the head of the legions he had formed on a campaign to the south of Gaul, acted extremely carefully and prudently. He strictly followed the advice of the Syrian fortuneteller Martha, who was carried everywhere with him in a stretcher. During the maneuvers, the legionnaires acquired endurance and were tempered by camp life for two years.

Finally, in 102, the tribes of the Cimbri and Teutones set out to invade Italy. Then the consul Gaius Marius built a well-fortified camp on the banks of the Rhone at the confluence of the Isare. The “Barbarians” unsuccessfully attacked him for three days, suffering heavy losses. After this, the Teutons, stopping the useless assault on the enemy field fortress, moved through the Maritime Alps to Italian lands.

The army of Gaius Marius followed them. A big battle took place at the Sextian Waters (or Sextus), during which the consul forced the enemy to attack him on hilly terrain, which did not allow the numerous “barbarian” cavalry to operate successfully. The Roman legionaries achieved a great victory by ambushing the rear of the attacking Teutons and forcing them to retreat.

It is believed that about 90 thousand “barbarians” died in the battle of the Sextian Waters, and another 20 thousand, together with the Teutonic leader Teutobod, were captured. There was only one fate awaiting prisoners of war - to be sold into slavery.

Meanwhile, the Cimbri, led by the leader Boyorix, successfully crossed the difficult Alpine mountains, defeated the army of the consul Gaius Lutatius Catullus in a battle in the valley of the Adui River and remained to winter in the valley of the Pad (Po) River.

Gaius Marius hastily arrived from Rome to help Catullus. In 101 BC. e., July 30, near the small town of Verzella, a decisive battle took place between the 50,000-strong Roman army and the tribes of the Cimbri, who were literally destroyed without any pity. After the Battle of Vercellus, the Cimbri people ceased to exist as such.

The winners killed 140 thousand “barbarian” Germans (men, women and children); the remaining 60 thousand people were captured and sold into slavery. Thus, the Cimbri War was won by the consul Gaius Marius.

So, the commander Gaius Marius, who remained consul for four years, saved the Eternal City from the invasion of the German tribes of the Cimbri and Teutons. For his victory in the war against the “barbarians,” he was awarded the honorary title of “third founder of the city of Rome.”

Gaius Marius did not have the chance to remain one of the most recognized leaders of the Roman Republic until the end of his life. He would become a principled opponent of Lucius Cornelius Sulla, who was striving for a personal dictatorship, and would cross arms with him in Civil War, which shocked Ancient Rome. Gaius Marius, the famous winner and destroyer of the Cimbri and Teutone tribes, will lose to Sulla, as they say, outright.