Well, our Russelenburg is great! IN last time we visited the abandoned barracks. But they are not alone in our city. If under New Year we "went to the Semyonovites", simultaneously exploring the history of their regimental parade ground, now we will visit the Naval Guards crew. This is where memory lives. Yes, such that these buildings and in general this place must be protected, honored and shown to tourists. But no one needs this memory.

Reader, we have returned to Kolomna. This is a very beautiful place: we admire the bizarre interweaving of rivers and canals, the graceful ligature of numerous bridges, St. Nicholas Cathedral with an elegant bell tower and the Church of St. Isidore of Yuryevsky. It was while examining it that we went to Rimsky-Korsakov Avenue.

But what is ahead? A completely different green color, so unlike the color scheme of church domes. The notorious green grid. Torn, dirty, similar to swamp slime - obviously hanging for a very long time. What a contrast compared to the domes shining after a fresh restoration!

What different "greens"!

Yes, here it is, our next object - the Barracks of the Naval Guards crew, which have been abandoned for twenty years. Prospect Rimsky-Korsakov, 22 / Embankment of the Griboedov Canal, 133. The canal winds like a nimble snake at a distance, a little further merging with the Kryukov Canal. As a result, the barracks complex has two addresses. It could have had a third one, but the wedge-shaped section is separated from the Kryukov Canal by a school. We go around the complex where possible.

From the side of the avenue, everything is tightly closed, immured. It blocks the way, interferes with the inspection and obtrusively looms in the frame of a shabby blue fence. We see two buildings here: one is a little simpler, the other is decorated with a little more pomp. What is less simple is the house of Gascoigne. Its history dates back to the 18th century: the building was erected in the 1780s according to the design of an unknown architect. The first owner was Charles Gascoigne (1739 - 1806) - a famous engineer from Scotland, who worked in Russia at the royal invitation. In his homeland, he was the owner of a metallurgical company, became famous for the invention of a short-barreled ship's gun, which was soon "adopted" by many countries. In Russia, they wanted to see him for a long time and called him more than once. And now he finally deigned to come here to start a big construction and be the director of the Izhora factories. " In May 1786, after repeated invitations, he arrived in Russia, where he built and reconstructed several factories. The first order of Empress Catherine II was the restructuring of the Olonetsky factories in Petrozavodsk according to European technologies: the Alexander cannon and the Konchezersky iron-smelting plant.

In 1789, Gascoigne built an iron foundry in Kronstadt, which was transferred in 1801 to the capital on the 4th verst of the Peterhof road (today the famous Kirov Plant begins its history from this enterprise). In the mid-1790s, at the request of Count P. A. Zubov, the master led the exploration of iron ore and coal deposits in Ukraine. The result was the foundation of a city-forming foundry in Lugansk, which until the 70s of the 19th century remained the only mining plant in the south of Russia.

In St. Petersburg, Charles Gascoigne (in Russia they began to call him Karl Karlovich) reconstructs production in Sestroretsk and the Admiralty Izhora factories in Kolpino, builds the Bank Mint. Kolpinsky project was the last in the life of Gascoigne. He died in Kolpino in 1806 and, according to his will, was buried in Petrozavodsk. The grave has not survived to this day.", - writes about him. His address was simple: Malaya Kolomna, his own house. And everyone knew this house. After the death of "Karl Karlovich", his daughter Anna Gaddington did not want to live at the "hereditary address" and sold the house to the Naval Department. The case “On the purchase of a house left after the actual State Councilor Gascoigne” is located in the Russian State Archives of the Navy.

“On June 4, 1808, the chief architect of the Admiralty, Andrian Zakharov, examined the mansion and found it quite suitable for accommodating a marine printing house. He reported that a solid house was built at the end of the 18th century, it consists of a three-story main building, a two-story outbuilding, and a one-story barn. In the garden, which, as it is said, "on the canal to the St. Nicholas Church" - stone greenhouses. On August 19, 1808, Emperor Alexander I allowed the Admiralty Department to buy a house from the heiress for 110 thousand rubles for a printing house.

A description of Gascoigne's house was found in historical essay S. Ogorodnikova about the marine printing house: “... the house, built on a master's foot, was stone, two-story with fifteen windows along the facade, with a mezzanine and two side outbuildings. Round columns with cast-iron bases gave the main middle building an elegant look, and a cast-iron main staircase with the same handrail and mahogany handrails led to the inner apartments. At the house there was an orchard and greenhouses, which came at the same time at the disposal of maritime minister. In the courtyard there were two stone two-story outbuildings.(ibid.).

His house is now, of course, ruined. It is unlikely that the apartments, the garden and the valuable stairs have been preserved inside. But the splendor of the facade will not hide any grid. The house is still very beautiful, and it's just scary for him.

House of Gascoigne.

I wonder why such a significant person settled in a rather "simple" part of the city - Kolomna? It's simple - this is the award of the Empress. In 1795, Catherine II granted Gascoigne the rank of state councilor, the Order of St. Vladimir III degree and donated a plot of land. It was already then a site of the Naval Regimental Court, where the officials of the Maritime Department settled. A little later, the military will also settle here (this will be the territory of the sea settlement). Then Rimsky-Korsakov Avenue was called Ekateringofsky.

And it all started like this. In 1736 there was a fire that destroyed almost all the previous buildings. A year later, the site was handed over for the construction of the Barracks of the Naval Guards Crew. And by 1742, the area was finally drained and the first regimental barracks were built from the side of the embankment. But while we have not yet reached it - we are on Ekateringofsky Prospekt, we have just admired Gascoigne's house.

And the next building is already concise. No columns, no curly architraves. Now this is the barracks. But would you, the reader, know whose it is!..

The building of the barracks from the side of the avenue.

The site, as we know, is wedge-shaped. By the way, it is also interesting because it had such a form almost from the very beginning and did not change this form. It so happened: this fact is due to the geographical location (you can look at the old plans).

We return back. We pass the barracks, go around Gascoigne's house. We stop a little on the corner. Since the site is of a peculiar shape, the angle is effectively bevelled.

And here we are on the Griboyedov Canal (formerly Ekaterininsky).

Barracks complex, view from the embankment.

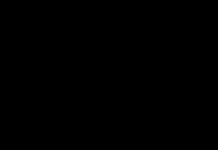

Barracks complex, view from the embankment. What an original shape this building has! The building is long, but not at all monotonous. It goes in ledges, resembling a military fortress. This "fortress" is closed by gates. It's amazing, but there is someone on the territory of an abandoned complex! And these are clearly not homeless people: some people are trying to drive us away from these gates. We rightly object that in our city we can photograph whatever our heart desires. And the citizens would be better off watching the buildings entrusted to them or preparing for the withdrawal (long overdue). We still get this shot - a view of the "fortress" from the yard. As you can see, the "non-ceremonial" facades are as simple as possible, and have neither "ledges" nor other expressive elements. And again, the broken windows are striking - the almost complete absence of conservation, which was limited only to hanging a grid and a false facade from the side of Rimsky-Korsakov Avenue.

Yard facades from the side of the Griboyedov Canal.

Yard facades from the side of the Griboyedov Canal. So, no one can forbid us to photograph the monument. Under current law, we generally have the right of access. However, for some reason, this legislation does not work. And it is not yet possible to photograph the rest of the buildings of the complex: they are not visible from the street.

We have to "act secretly." Photographer Olga Rodionova managed to elude the guards and penetrate into the "impregnable fortress". Olga generously agreed to provide her pictures for publication in our publication. This is what she saw inside:

This slideshow requires JavaScript.

Barracks inside (photo by Olga Rodionova).

As you can see, there are almost no interiors left in the building. Everything has been taken out. Either during previous repairs, or at a time when the military was leaving the complex. Only one beautiful hall has survived. And the rest - a typical "settlement" landscape: dirt, dust, old documents, wet portraits of military leaders and members of the Politburo, newspaper photos of party congresses, other household items in disarray. Unless the devastation is smaller - they still protect. But the balustrade on one of the stairs is gone.

But what can we say about respect for the monument, even if a real leapfrog was going on with its protected status! "Let's listen" to the most experienced journalist-city defender Tatyana Likhanova: " The significance of this complex, built at the end of the XVIII-XIX centuries. on the corner section formed by the rays of Ekateringofsky (Rimsky-Korsakov) Avenue and the Ekaterininsky Canal (Griboedov), they recognized in 1993 - by the decision of the small council they would be taken under protection as a monument of local importance. Then leapfrog will begin with a reassessment of values - in 1995, by decree of the President of the Russian Federation, the complex of barracks of the Guards crew will be given the status of a monument of federal significance, in 1999 they will be excluded from this register by order of the government of the Russian Federation, the next year, by order of the governor of St. to the protected elements of the complex of the barracks building for combatant and single lower ranks, the headquarters and chief officer's house with two service buildings, a bathhouse and an emergency room».

The text "Abandoned and Forgotten" Tatyana Ivanovna wrote for the bicentennial anniversary of the war of 1812. Since then, absolutely nothing has changed here: the text is still fresh, like from today's newspaper.

What's with the war?

Moreover, dear reader, these are not just barracks. This is the barracks of the heroes of 1812! "AND The history of the Naval Guards crew dates back to Peter the Great, who in 1710 gathered a team of royal rowers from among the “amusing Pereslavl” in order to “entrust himself to them in traveling by water.” Many of them will become heroes of quite serious battles - the capture of Azov, Noteburg, Nyenschanz - and become involved in the founding of a new Russian capital. Independent marine part Guards will be established by decree of Alexander I in 1810. Both officers and lower ranks were transferred to the Guards crew only for special merits known to the emperor personally or on the special recommendation of his superiors. They were trained not only in military wisdom, but also in artillery - the uniqueness of this unit consisted in combining the actual naval service on court rowing vessels, yachts and ships and coastal service as an infantry battalion of the Guards Corps of the Russian Imperial Army. During the Patriotic War of 1812, they performed the functions of engineering troops”, continues Likhanova (ibid.). Further in its text, you can learn about the greatest merits, as they say now, "an elite military unit." The author of these systems will only have to add that the chiefs of this unit were emperors and princes, and the commanders were such personalities as Abaza, Klokachev and Apraksin (lists of personalities and). But, despite this, the buildings were “debunked”: memorial plaques disappeared from the facade, and something is not visible inside, on the stairs, embedded in the wall of military relics-trophies: the Turkish coat of arms and a marble plaque from the main gate of the Turkish fortress Ruschuk in Bulgaria, taken by the guards as a trophy (information gleaned).

Barracks in the pre-revolutionary period (photo from Citywalls).

Barracks in the pre-revolutionary period (photo from Citywalls). The “fortress building” overlooking the canal was built in 1797. Prior to that, there was a section of the Regimental Court, the house of the merchant Anuryev and the house of the merchant U. Ivanov (ibid.). Whether Gascoigne had one neighbor or two is unknown. Either it was a single plot that passed from one owner to another, or there were two owners. History is silent. But, one way or another, in 1797, the year begins here, and in 1819, the construction of the barracks of the Naval Guards crew continues (already from the side of the canal). In the same year, sailors moved here (before that, the Guards marine crew lodged in the Galernaya Harbor area, and after that in the Lithuanian Castle).

And in 1825, on December 14, the Decembrists who served here raised all the units of the troops and, led by Nikolai Bestuzhev, went to Senatskaya. So the Decembrist uprising was born precisely.

In 1853, the complex was rebuilt by military engineers Pasypkin and Matyushev. The second part of the century passed without high-profile events. The twentieth century brought a revolution and the disbandment of the valiant Crew. Not far from here, in the Kryukovsky barracks, a headquarters of revolutionary sailors and a sailors' club arose. And here the Sailor's Theater was opened. And on December 17, 1918, Vladimir Mayakovsky read here the Left March specially written for this speech. As the poet later admitted, he already had separately prepared stanzas, and the poem itself developed quickly, along the way, in a cab (“Speech at the Komsomol House of Krasnaya Presnya at the evening dedicated to the twentieth anniversary of activity, March 25, 1930”).

After the times of Mayakovsky, the once legendary buildings were never seen by any other famous person: the complex was transferred to the Naval Base. It was used for administrative purposes and for housing (on the Citywalls.ru website, a former cadet of the naval faculty of the LISI writes that he lived there from 1955 to 1960). They also write that the base kept a headquarters here, and even with a guardhouse. After the war, in the 40s-50s, there was another restructuring here. And half a century later, in the late 90s, the base left the territory - moved. For some time the complex stood unoccupied (for all that, the headquarters and chief officer's house, the barracks for single lower ranks, the barracks for combatant companies and the service wing are included in the register of monuments). Then the complex was bought by a certain Moscow company - CJSC Construction Management No. 155. As they wrote in the press, the largest player in the Russian construction market. The owner intended to turn the barracks into a business-class residential complex. But, as the media writes, he had problems with the KGIOP, which could not draw up a security obligation (http://kanoner.com/?s=barracks+crew). In 2013, the same unhurried KGIOP wanted to force Muscovites to start work and even fined them. The parties blamed each other for the delay, KGIOP denied its own statements, and gradually the owner lost interest in the object. Newspapers of 2013 wrote that the SU-155 was "beginning a study of the barracks", intending to demolish the Soviet buildings. Then everything went silent. And in 2017, it became known that the company was undergoing reorganization and that it was a real bankrupt! As a result of the difficult financial situation, all her projects hung up: in addition to the barracks, the reconstruction of the chief prosecutor's house on Liteiny Prospekt and the Orlov-Denisov dacha in Kolomyagi arose. It got to the point that they tried to sell the chief prosecutor's house along with the project to Avito! Obviously, the company has completely gone around the world ...

The unfortunate barracks, of course, do not care about the problems of their unlucky owner. They are waiting for caring hands. Logically, they should be withdrawn, and it is not clear why Smolny is still “rushing around” with the bankrupt and giving him another last, desperate chance. Pity is inappropriate here: the old legendary buildings are much more pitiful. Broken windows, from which wonderful views open, are thrown open into the unknown. What are they waiting for? The one that will recover after many years is the unfortunate "SU", and, perhaps, in a thirst for clearing the territory, it will declare several historical buildings to be Soviet. And there will be a "big city defense battle" here. If the building is withdrawn, how soon will they find a new owner? And will this owner be reliable? I would like to…

But here's what, to be honest, I would not like - so it's the next "elite apartments". Not out of some kind of envy, as one might think. No, it's just that this area breathes former glory. The wind ruffling the tattered mesh could have fluttered the flags of past victories. A place that remembers Mayakovsky and Bestuzhev with associates is worthy of a much more respectful purpose than the prospects of the next "elite". It would be much more appropriate to place a museum here. Let's say, with state assistance, to settle in at least one building the Museum "XX Century", which has recently lost large premises.

The window is wide open into the unknown (photo by Olga Rodionova).

The window is wide open into the unknown (photo by Olga Rodionova). Daria Vasilyeva, especially for "GP".

Photo by the author, Olga Rodionova and from citywalls.ru.

Klyuev Egor

We know the great names of Kutuzov, Bagration, Dokhturov. Denis Davydov. But we know very little about the participation of Russian naval forces in this war. And the sailors of the Russian fleet, mainly the Baltics, played significant role in the fight against the enemy. Guards crew- a naval formation as part of the Russian Imperial Guard. It was a truly unique military formation. Constructing bridges and crossings for other branches of the military, the sailors-guards, along with everyone else, led fighting, showing examples of selfless courage and endurance. The Naval Guards crew literally paved the way for their army and made it difficult for the enemy army. The uniqueness of the Marine Guards Crew was the combination of naval service on court rowing vessels, yachts and ships and coastal service as an infantry battalion of the Guards Corps of the Russian Imperial Army.

Download:

Preview:

Naval Guards crew

in the Patriotic War

1812

and the foreign campaign of the Russian army in 1813-1814.

Study

INTRODUCTION

This year marks 200 years since the beginning of the Patriotic War of 1812. We know the great names of Kutuzov, Bagration, Dokhturov. Denis Davydov. But we know very little about the participation of Russian naval forces in this war. And the sailors of the Russian fleet, mainly the Baltics, played a significant role in the fight against the enemy. The sailors of the Guards crew, an elite unit of the Russian fleet stationed in St. Petersburg, successfully fought the enemy. The Guards Crew is the only naval unit of the Russian Guard in pre-revolutionary Russia. The first time I read about the Naval Guards crew was quite recently, preparing for an exhibition dedicated to the Patriotic War of 1812, and studying Russian military uniforms of that period. I was interested in this unusual formation in the Russian army, and I decided to collect materials on this topic and prepare a paper for the school scientific and practical conference, as I am sure that no one at school knows anything about this wonderful crew, about its glorious history, combat way and role in the war with Napoleon. In the year of the 200th anniversary, it will be interesting and useful to open new pages in the history of the Patriotic War of 1812.

The traditions of serving the Fatherland have always been strong in the Russian Navy. Examples of this are the famous Russian naval commanders: F.F. Ushakov, P.S. Nakhimov, outstanding navigators: I.F. Kruzenshtern, F.F. Bellingshausen, M.P. Lazarev, and ordinary sailors, whose names we do not know, but whose courage and stamina are worthy of memory and respect. These traditions are passed down from generation to generation.

So the topic my research:Naval Guards Crew in the Patriotic War of 1812 and the Foreign Campaign of the Russian Army of 1813-1814.

Problem: what was the necessity and uniqueness of this military formation?

Objective : highlight the role of the Guards crew in World War II.

Tasks:

- study the literature and other possible sources of information on the topic;

- highlight and describe the most important facts and events from the history of the Guards crew;

- analyze these facts and events.

Of course, there is no material on the topic in our libraries, so the main source of information will be the Internet.

MAIN PART

1. The history of the creation of the Guards crew

Guards crew- a naval formation as part of the Russian Imperial Guard. The Naval Guards crew was created in the reign of Emperor Alexander I on February 16, 1810, but it originates from a team of court rowers who appeared under Peter I in early XVIII in. The “Rowers of the Kings”, who at that time did not constitute a permanent team, participated in the first battles of the Northern War, the capture of the fortresses Noteburg and Nyenschanp on the Neva, the capture of the Swedish ships Gedan and Astrild, etc. When the capital was moved to St. Petersburg, for navigation of the sovereign on the Neva, Moika, Fontanka, special boats were identified and in 1708 a team of rowers was created, which later received a special uniform. During the XVIII century. the number and subordination of court rowers changed. From the middle of the eighteenth century there was a team of court rowers of the palace department and crews of court yachts, they were united in 1797 and transferred to the jurisdiction of the Admiralty College. Under Catherine II, the number of rowers reached 160 people, they were divided into the Court Yachting Team and the Court Rowing Team. During this period, rowers served 6 yachts. Under Paul I, in 1797, both teams reunited and were named the Court rowing team of court sailing ships. The team received a military organization.

From these units, on February 16, 1810, the “Naval Guards Crew” was formed from four (later eight) companies, an artillery squad with two field guns, a non-combatant flipper company and a musical choir (orchestra). According to legend, the French Guards crew, which Alexander I saw during a meeting with Napoleon in Tilsit in 1807, served as the prototype of this formation. The best officers from the fleet were taken to the Guards crew by the personal order of the Sovereign, for special distinctions; when choosingthe teams were guided by the fact that people were “tall” and “clean in face”; special attention was paid to combat infantry service, and Grand Duke Konstantin Pavlovich himself oversaw this. Thus, the Guards crew began its existence as in the highest degree an elite unit and remained so until its abolition on March 3, 1918.(By this date, even the Emperor was in the crew).On January 6, 1811, a review of the crew took place, where he earned the praise of the emperor, and awards were presented to the officers and sailors.

The crew was assigned a special uniform, somewhat different from the general fleet, with elements of uniforms of the guards infantry: the summer uniform was like in the navy, and the winter uniform was modeled after the guards infantry.

The funds of the Central Naval Museum contain the uniform and uniform of an officer of the Guards crew of the first quarter of the 19th century. (Inv. No. 11272, 11258). The tailcoat cut uniform is made of thin dark green cloth, double-breasted, with two rows of convex gilded buttons on the chest with a diameter of 19 mm. Tailcoat and collar lining in uniform cloth. On the lining of the fold, transverse welt pockets are made. The collar is standing, closed in front, as was established in January 1812, fastened with four hooks and four loops. On the collar there is gold embroidery in the form of a horizontal anchor intertwined with one thick and three thin ropes, and a gold piping along the edge. There is a gold edging on the cuffs of the sleeves along the edge, and on their valves there are 3 sewn anchors intertwined with ropes.

The uniform is made of the same cloth, but differs in that there are four on its collar, and three sewn gold buttonholes on the cuff flaps. Uniform buttons are flat with a diameter of 23 mm.

The lower ranks at that time wore a double-breasted dark green uniform without tails with copper buttons, red shoulder straps, white piping along the edges of the collar, cuffs and valves. On the collar and cuffs are buttonholes made of guards red-yellow "checkered" braid. The non-commissioned officers had a collar and cuffs, in addition, trimmed with gold galloon. Trousers made of dark green cloth relied on the uniform in the winter uniform, and in the summer– white from flamese linen. Just such a set of non-commissioned officer's uniform of the 1810 model (Inv. No. 9375) is in the museum's banner fund. This is an exact copy of the clothes of that time, but sewn already at the beginning of the 20th century, most likely for the 100th anniversary of the Guards crew, celebrated in 1910.

According to the staff, the sailors of the crew were provided with combat equipment and property of a land sample, including a entrenching tool and a wagon train. The personnel served on imperial yachts and boatspalaces, was involved along with the entire guard to the guards, reviews, parades, celebrations.

The word "guard" itself comes from the Italian guardia, which means guard. The Life Guards were traditionally called the elite part of the troops, who were entrusted with the protection and protection of the monarch, as well as other high-ranking persons (from German Leib - body). Excellent training, high professionalism and firm adherence to regimental traditions have been the hallmarks of the Russian guard since its inception at the turn of the 17th-18th centuries.

Along with serving in the capital and suburban residences, sailors participated in long-distance voyages of Russian ships. Almost every sailboat that sailed around the world had a guards officer. They made foreign voyages and individual ships, manned by guardsmen. The frigate "Hector" and the brig "Olympus" went to France, England and Prussia in 1819. In 1823 the frigate Provorny approached the Faroe Islands and Iceland, bypassed Great Britain and returned through the English Channel and the North Sea to the Baltic; a year later he went to Gibraltar, Brest and Plymouth. The battleship "Emgeiten" sailed to the Rostock area.

The first ship of the Guards crew of Russia was the 74-gun sailing battleship Azov, commanded by Captain 1st Rank MP Lazarev, a well-known naval commander in the future. On October 8, 1827, he participated in the famous Navarino battle the combined fleet of Russia, England and France against the Turkish-Egyptian fleet.

Fighting simultaneously with five Turkish ships, "Azov" destroyed four, and the fifth - an 80-gun ship of the line under the flag of the commander of the enemy fleet forced to run aground. In this battle, the officers of "Azov" especially distinguished themselves: Lieutenant P.S. Nakhimov, midshipman V.A. Kornilov and midshipman V.I. Istomin.

Of the 600 crew members of the Azov, 153 were killed and wounded. Later, 153 holes were counted in the Azov hull, including seven underwater ones. But the heroic battleship did not withdraw from the battle until the enemy was defeated.

The highest award for successful military operations in this battle was awarded to Azov - the ship was awarded the St. George admiral's flag (as a stern flag) and the St. George pennant. “In honor of the laudable deeds of the chiefs, the courage and fearlessness of the officers and the courage of the lower ranks,” the imperial decree said.

When created, the Guards crew was subordinate to the naval leadership - the Admiralty Board; but, being an integral part of the Sovereign Guard, he was also subordinate to the land authorities.

2. Guards crew in the war of 1812

The crew received its baptism of fire in the Patriotic War of 1812. With the beginning of 1812, the Sovereign Guard began to prepare for the campaign, but the Naval Guards crew did not receive instructions on this matter. However, on February 28, Minister of War Barclay de Tolly sent a crew to speak in Vilna on March 2. The crew was assigned to the 1st Division of the 5th Guards Corps, commanded by His Highness Grand Duke Konstantin Pavlovich. Only two days were given to prepare for the campaign. When speaking on a campaign, the crew included 436 lower ranks and 18 officers and employees. The crew included 17 Knights of St. George. 91 people from the crew remained in St. Petersburg. On March 1, an artillery team of 40 people was seconded to the submission of Major General of Artillery Yermolov. The team received two light guns from the land department. On March 5, she set out on a campaign together with the Life Guards artillery brigade as part of one light company under the command of the brigade commander, Colonel Euler, and was almost inseparable with this brigade throughout the campaigns of 1812-14. The commander of the Guards crew was Captain 2nd Rank Ivan Petrovich Kartsov.

March 2 at 10 am the crew in fully prepared and with his convoy appeared at the Highest review along with the Life Guards Jaeger and Finnish regiments. Saying goodbye to each regiment separately, the Sovereign said: "Farewell, guys, I hope that I was not mistaken in taking you with me, and that you will show me your service." Sailors under the command of Captain 2nd Rank I. Kartsev, as part of the 1st Division of the Guards Corps, set out on a campaign from St. Petersburg to Vilna.

They arrived in Vilna on May 28. Upon arrival, the sailors did not stay for long in the vicinity of the city. On June 2, on the orders of the commander of the 1st Guards Infantry Division A.P. Yermolov, three companies of the crew set out on a campaign to Drissa to participate in the work to strengthen the Drissa camp, where, according to the project of the German military specialist Ful, it was supposed to give battle to the attackers. On June 16, the crew began to build bridges for the crossing of the retreating troops. The 2nd company was sent to Nemenchyn at the disposal of engineer-colonel Manfredi to build bridges on the river. Vileika for crossing the retreating corps of P.Kh. Wittgenstein, as well as through the river. Viliya, along which the convoy of the entire Russian army then crossed, the 4th corps under the command of P.A. Shuvalov and the 2nd Corps of K.F. Baggovut. All bridges were built from rafts made of logs and boards with barrels placed under them for buoyancy, and baskets filled with stones served as anchors. After the construction of the crew, the crew continued to stay near the bridges to guard the crossing.

Among the old guards of Napoleon was the guards marine crew of about 1000 people, formed in 1798 and already managed to earn fame in the wars with Spain and Austria. Near the Berezina, almost all of this crew died.

On the night of June 11-12 (old style) French troops and their allies crossed the border. The retreat of our troops began. On the third day after receiving the news that Napoleon had crossed the border, the first retreating units of Count Shuvalov's corps arrived. The crossing was successful, and at the end of it it was ordered to destroy the bridge, as a detachment of French cavalry appeared.

Together with the troops of the 1st Western Army, General M.B. Barclay de Tolly, the sailors-guards retreated into the interior of the country under the onslaught of Napoleon's superior forces. The crew followed in the rearguard, was used mainly together with engineering units in building crossings, building bridges and fortifications, setting up camps; often sailors had to destroy buildings and property so that they would not go to the enemy. After the decision to leave the Drissa camp on July 2, the crew ensured the crossing of the Russian army to the right bank of the Dvina, and then, together with the pontoon companies, was engaged in dismantling bridges and destroying building materials, which the French could get, and also destroyed water mills on the rivers to make it difficult for the French to harvest flour. On July 14-15, for the crossing of the 1st Western Army across the Dvina, the crew built bridges, which, after the passage of the troops, were immediately destroyed. For masterful actions in building bridges in the Drissa area in the presence of Alexander I, the sailors were granted cash prizes from the emperor.

Together with the 5th Guards Corps, the crew moved to Smolensk. An important task for the 3rd company of the crew under the command of Lieutenant Titov was the construction, together with the pontoon company, of bridges across the Dnieper, along which the 2nd Western Army of P.I. Bagration crossed to connect with the 1st Western Army in Smolensk. During the battle near Smolensk on August 4-6, the Guards crew ensured the passage of Russian troops along the bridges across the Dnieper, and after that they blew up the bridges with mines.

The crew fought the first battle on August 4 during the defense of Smolensk, repulsing the attacks of the French cavalry on the Royal Bastion and the bridge across the Dnieper. When forced to leave the city, sailors and pontooners destroyed this bridge.

Having finished their actions at the crossings in Smolensk, the crew and pontoon companies moved with our armies along the Moscow road. Due to continuous rains and heavy traffic, the path was very difficult.

On August 17, both armies settled in Tsarevo-Zaimishche, where the new commander-in-chief arrived.

On August 21, the 5th Guards Corps arrived at the Kolotsky Monastery, and on the 22nd to the village of Borodino. From Smolensk to Borodino, the army marched more than 300 miles - an unprecedented organized retreat of more than a hundred thousandth army. The order to a large extent depended on the serviceability of the crossings, in the arrangement of which the sailors of the Guards crew participated.

3. Guards crew in the Battle of Borodino

At the position near the village of Borodino, the Guards crew, along with other troops, participated in the construction of fortifications, and during the battle most of it was in reserve. On the morning of the Battle of Borodino on August 26, 1812, the crew met on the extreme right flank of the Russian army. By order of Barclay de Tolly, the sailors were sent to help the guards rangers who were defending the village of Borodino from the attacks of Delson's division. A detachment of 30 hunters under the command of midshipman M.N. Lermontov was stationed together with the 2nd battalion of the Life Guards of the Jaeger Regiment in the village of Borodino near the bridge over the Kolocha River, they were instructed to destroy the bridge in the event of an enemy breakthrough. For this, combustible materials were prepared on the bridge. On August 26, at four and a half in the morning, Delson's division, taking advantage of the darkness and fog, quietly approached the village and launched an attack on Borodino. The Life Guards Jaeger Regiment repelled the onslaught of the French for about an hour, but was forced to retreat. Following him, the 106th French line regiment crossed the bridge. At this time, to help the defenders of the bridge, the commander-in-chief of the 1st Western Army M.B. Barclay de Tolly sent the 19th and 21st Chasseurs. Together with them, the sailors of the Guards crew went on a counterattack. Sailors-Guards threw back the enemy, and then destroyed the bridge across the river Kolocha. The 106th French regiment suffered heavy losses. Following this, the sailors set fire to and destroyed the bridge. In the battle, four sailors and a non-commissioned officer died a heroic death, seven were seriously injured, and subsequently two of them died. The gunners of the crew, who were part of the 1st Life Guards Light Artillery Company, took an active part in the battle. On August 26, after the loss of the Semyonovsky flashes, when the battles for the Semenovsky ravine began, along with other parts of the reserve, two guns of the guards crew, which were part of the 1st Artillery Company, were called. In the middle of the day, under the command of staff captain Lodygin, they advanced to a position near the village of Semenovskoye on the left flank. Positioned on a hill, together with the guards infantry regiments that stood in a square, the artillerymen repulsed the attacks of the enemy's heavy cavalry. In five hours of fierce fighting, they lost all officers killed and wounded, four sailors were killed. The company spent more than 4 hours under the destructive fire of the enemy battery and withdrew from the position only when it noticed that the French attack had been interrupted. At 9 pm, staff captain Lodygin again led the company to Semenovsky, when the Finnish Life Guards Regiment repelled the attack of the French infantry. Already in the darkness, the artillerymen helped to cope with the enemy. These were the last artillery shots of the Battle of Borodino. Several officers of the Guards crew that day served as adjutants to the high command. Michman N.P. Rimsky-Korsakov repeatedly delivered orders from Commander-in-Chief M.I. Kutuzov, earning praise for his fearlessness and ingenuity. Captain-Lieutenant P. Kolzakov fought on the Semyonovsky flashes, the first to rush to the aid of the wounded P.I. Bagration.

In the Battle of Borodino, the Guards crew had a share, without taking part in the battle with the entire crew, to have their fighters among the first troops that started the battle, and among the last to finish it.

French losses at Borodino amounted to 28 thousand, Russian - 46.5 thousand people, including 29 generals. Heavy losses and the delay in the arrival of the promised reserves prevented Kutuzov from resuming the battle the next day. He gave the order to retreat to Moscow.

On September 1, in the village of Fili, three versts from Moscow, a military council was assembled. Kutuzov raised the question: “Should we expect an attack on a disadvantageous position or cede Moscow to the enemy?” Opinions were divided, but Kutuzov decided: to leave Moscow in order to save the army, because with the loss of the army, Moscow would also be lost and the entire campaign would be lost.

4. After the surrender of Moscow

The next day the French army approached Moscow. In vain Napoleon waited on Poklonnaya Gora for the deputation of the "boyars" with the keys to the city. Moscow was empty: out of 270 thousand of its inhabitants, about 6 thousand remained in it. The retreat of the Russian army through Moscow was so hasty that the enemy got rich warehouses with weapons, ammunition, uniforms, food. Were left at the mercy of the winner and 22.5 thousand wounded in hospitals in Moscow. On the same night, fires broke out in different parts of the city, which raged for a whole week. More than 2/3 of the buildings were destroyed in the fire. The victims of the fire were many of the remaining residents, as well as the wounded in hospitals. From Moscow, Napoleon repeatedly turned to Alexander I with proposals for a peace. Asked about this Arakcheev and Balashov. But Alexander was adamant.

On September 2, in the morning, the Guards crew entered Moscow and was near the bridges across Moscow and the Yauza, along which our army crossed, heading for the Ryazan road. It was not an easy task for the sailors to keep order at the crossings, as thousands of Muscovites with their belongings tried to leave the city together with the troops. On September 4, when the troops crossed, the bridges were lit by Lieutenant Afanasy Ivanovich Dubrovin and Midshipman Nikolai Petrovich Rimsky-Korsakov. The vanguard of the French at that time was already occupied by the Kremlin.

On the evening of September 4, the crew settled down on the right bank of the Moskva River at the Borovskoye ferry, awaiting the passage of troops. In front of the eyes of the French cavalry, the sailors destroyed the bridge while under fire. 3 sailors were mortally wounded. After this operation, the crew was urgently requested to cross the Krasnaya Pakhra, where, from September 7, they took part in laying the pontoons.

"The enemy has begun to sit in Moscow." After the surrender of Moscow, the crew was in the Tarutino camp. By September 25, the infantry units consisted of 10 officers, 25 non-commissioned officers and 319 sailors and were attached engineering troops. The artillery team (2 officers, 6 non-commissioned officers and 25 gunners) with two guns became part of the 23rd artillery brigade.

5. Napoleon's retreat

The French army was in Moscow for 36 days. On September 28, a second fire broke out in the city. After a month's stay in the capital, Napoleon decided to move back.

Before leaving Moscow, on October 7, Napoleon gave the order to blow up the Kremlin and the Kremlin cathedrals, to destroy what the fire had spared. Fortunately, only the Ivan the Great Bell Tower and the Nikolskaya Tower of the Kremlin were damaged.

The crew at that time was quartered in the village of Ovchinnikovo south of Moscow. On October 11, an order was received from the commander-in-chief to urgently build bridges across the Protva. The crew made a quick march to the indicated place. I had to move in the pouring rain and almost all the time running. Due to the lack of materials, it was necessary to dismantle the peasant huts left by the inhabitants. After 6 hours, two floating bridges were built, one for the infantry, and the other for the cavalry and artillery. The third bridge was only half completed. It was about 9 pm when the vanguard of the army approached the crossing. Thanks to the speed of work, the entire corps of General Dokhturov crossed by the morning of October 12 and proceeded to Maloyaroslavets, preventing the French from fortifying themselves and arranging a convenient crossing there. Following Dokhturov's corps, on the same day, the commander-in-chief arrived with the army. Bridges were weak. Logs and boards sank. Ties from branches and poles spread. But before dark the army crossed. Kutuzov was extremely worried. Having summoned the commander, he, on the whole, expressing satisfaction, said: “If something happened to the detriment and detention of the troops at the crossing, I would order you to be shot. You should have foreseen all the shortcomings and needs even in Ovchinnikovo.

The retreat of the French along the Smolensk road began. An artillery group of sailors took part in the battle of Krasnoe. The sailors were on the right flank when delivering a decisive blow to Davout's corps.

November 11, the crew came to the town of Kopyse on the Dnieper. Deep snow, cold, fatigue of horses forced them to drag wagons and guns on their hands. In Kopys, it was ordered to build bridges across the Dnieper. I had to work standing waist-deep in water, with ice drift. The victims of such work were three sailors who died in Kopys. Here the crew received sheepskin coats and winter boots.

On November 14, the crew set out in the city of Borisov on the Berezina River. 3Here he began to build a bridge on the goats. Again I had to work waist-deep in icy water. The crew suffered serious losses: the sailors died from diseases.

Shortly after the occupation of Vilna on December 11, the Sovereign arrived and took command of the army. From the report it followed that there were 12 officers and 355 lower ranks in the ranks of the crew. From the day they left Petersburg, the losses were: 16 killed, 26 dead from wounds and diseases, 8 missing. In addition, the artillery team lost 6 people killed and 5 people died from wounds and diseases.

Parking in Vilna gave the opportunity to rest and put things and ammunition in order. On December 23, an order was received to move to the border, where the crew arrived on December 30.

The actions of the crew in the campaign of 1812 were so noticeable that Admiral P.V. Chichagov, the commander of the South Danube Army, also wished to have a detachment of sailors, and he was allowed to summon the 75th ship's crew from the Black Sea under the command of Captain 1st Rank Dodge. In the campaign of 1813, this crew worked in the construction of bridges and crossings, and where necessary, rendered them unusable.

On March 27, the army moved through Silesia, the cities of Steinau, Bunzlau, Bautzen and Dresden, where they arrived on April 12. The death of the commander-in-chief was a heavy blow for our troops. The crew had the honor to say goodbye to Kutuzov when the crew passed through Bunzlau.

The sailors participated in the counteroffensive, fought in Poland, Germany and France. The army continued to move now in alliance with the Prussian troops, since an agreement on joint actions was concluded with Prussia. On May 1, the crew joined the army in Bautzen, and this time they had to face the enemy in battle in full view of the Sovereign. By this time, Napoleon managed to gather troops that outnumbered the troops of the allies: Russia and Prussia. Napoleon's superiority in strength and his capture of fortresses on the Elbe forced the allies to abandon the defense of Dresden and retreat to Bautzen. The position of the allied forces was aggravated by their failure on April 20 in the battle of Lutzen. On May 8, Bautzen, occupied by the troops of Miloradovich, was taken by attack by the sailors of the Kompan division. The French launched an offensive on May 8 at 10 am. The course of the battle turned out to be for us. But Emperor Alexander I insisted on the need to continue the battle, fearing a decline in morale in the troops and the evasion of Austria, with which negotiations were carried out, from an alliance with us. The naval crew was part of the main reserve under the command of Grand Duke Konstantin Pavlovich in the following composition: 2 staff officers, 8 chief officers, 14 non-commissioned officers, 18 musicians and 179 lower ranks. The artillery team consisted of 2 chief officers, 4 non-commissioned officers and 19 lower ranks. Total: 12 officers and 234 lower ranks.

May 9 came, a memorable day for the crew - the day of the battle on the temple regimental holiday. The relocation of the relics of St. Nicholas the Wonderworker, the patron saint of sailors, was celebrated. Alexander I rode up to the ranks on horseback and said: “Hello sailors! I congratulate you on the occasion! Today is your holiday, and I want to amuse you for the holiday: go to work. I will look at you." Unanimous "Hurrah!" and “Glad to try!” was the answer. The well-aimed fire of our batteries stopped the French attacks, but they, reinforced by fresh reinforcements, began to overcome. The sovereign sent a detachment of Lieutenant General Cheglokov to replace the Prussian General Count York. The detachment included the Naval Guards crew. The battalions and with them the crew stood in their positions when most of the allied troops were forced to retreat. At about 5 o'clock, Lieutenant Commander Grigory Kononovich Goremykin was killed, Lieutenant Alexander Andreevich Kolzakov was mortally wounded in the legs by a cannonball, midshipman Nikolai Petrovich Khmelev was seriously wounded. At 5 o'clock the general retreat began. The sun was already setting when it was the turn of Lieutenant General Cheglokov's battalions to retreat. The crew covered the retreat of the battalions, taking the last enemy cannonballs and grenades. Both sides suffered heavy losses. The losses of the Guards crew amounted to: 2 officers killed, 1 wounded; 6 lower ranks killed, 10 seriously wounded, as well as 4 non-commissioned officers and 5 sailors slightly wounded.

On August 14, the allies attacked Dresden, but Napoleon inspired the besieged with his presence, and the attack was repulsed. On August 15, the French attacked the allied troops, but unsuccessfully. The corps of the French General Vandamme was ordered to go behind the lines of the allies. On the night of August 15-16, the allied troops, fearing to be surrounded, began to retreat to Bohemia to the city of Teplitz. During the retreat, the Guards crew, with the participation of the Jaeger regiment, as well as the Preobrazhensky, Semenovsky and Izmailovsky regiments, repulsed the attacks of the French. In order to prevent Vandam's maneuver, a detachment of guard units numbering 10 thousand people was allocated, which included the Guards crew. The command of the detachment was entrusted to Lieutenant General Count Osterman-Tolstoy. Vandam's corps numbered 35 thousand people, that is, three times the strength of the Russians. It was decided to stop Vandam near the village of Kulm. Napoleon promised Vandam a marshal's baton if successful. General Yermolov played an important role in organizing the defense near Kulm. Alexander I was sure that his Guard would not allow the path of the Allied army to be cut. Additionally, the Sovereign ordered that the Prussian corps of General Kleist would separate from the main forces and rush to the aid of Count Osterman-Tolstoy. The Austrian emperor, whose troops had joined after the armistice, also sent two of his corps. The guards crew was first sent to the reserve, but did not stay there for long. The guards agreed to have a certain gathering place in case they were separated - a fruit tree in a meadow. Further than this place, it was decided not to retreat.

On August 17, at about 8 o'clock in the morning, French rifle chains began to descend from the mountains. Behind them were the columns of Vandam's corps. Soon there was a collision, and our vanguard was forced to leave Kulm and retreat. The French twice reached the main line of defense, but the Guard repulsed the attacks. The crew operated near Semenovtsy. Captain-Lieutenant Alexander Egorovich Titov was seriously wounded, the commander of the 1st company, Lieutenant Konstantin Konstantinovich Konstantinov was killed, Lieutenants Nikolai Petrovich Rimsky-Korsakov and Nikolai Petrovich Khmelev were wounded. Killed and seriously wounded up to 30 lower ranks. Repeatedly during the day, the French renewed their attacks, but to no avail. Of the officers in the crew, only three people remained. Therefore, the wounded lieutenants Dubrovin, Lermontov and Ushakov remained with the crew. Musicians, drummers and clerks took the guns of the dead and went into battle.

By the end of the day, reinforcements began to arrive. This made it possible to withdraw the guard to the reserve. The sailors gathered under the agreed fruit tree. The French, seeing a fierce rebuff, withdrew to Kulm. Thus ended the first day of the Kulm battle. It became known that the convoys that lagged behind during the accelerated march of the guard were looted, including the convoy of the Guards crew.

Among the losses that day was also Count Osterman-Tolstoy, whose arm was torn off. The command was taken by Major General Yermolov. Total losses the crew that day was 3/4 officers and more than 1/3 lower ranks.

On August 18, early at dawn, the main forces began to approach the Kulm position. The commander of the Russian army, Barclay de Tolly, and Yermolov, who arrived, did not start the battle, waiting for Kleist's corps to come closer. The French opened artillery fire. Around 10 o'clock it became known that Kleist was approaching. The battle began with a French cavalry charge. The infantry followed the cavalry. At first, the French bravely attacked our positions. Seeing the appearance of Kleist's troops, Vandam assumed that this was reinforcements from Napoleon. But when he recognized the Prussians and saw himself surrounded, Vandamme decided to surrender. The Allies captured 12,000 Frenchmen, Vandamme and two of his generals. Two banners, three eagles were captured; all his artillery fell into the hands of the allies - 84 guns and 200 charging boxes, the entire convoy. Up to 10,000 French were killed or wounded. Our losses were also heavy. The guards alone lost 3,000 killed and wounded in just one day on 17 August. For valor and feats shown in the battle on August 17-18, 1813 near the village of Kulm (now Chlumets, Czech Republic), the crew was awarded a high military award - the St. . Officers and lower ranks were awarded Russian, Prussian and Austrian awards. The place where the victory was won is decorated with three monuments: Russian, Prussian and Austrian troops.The heroism of the Guards crew at Kulm is also reminded by the commemorative badges of the crew, approved on February 8, 1910. They are based on the Kulm Cross, covered with black enamel, which was established by the Prussian king to reward the participants in the battle. In the center of the cross is the gilded cypher of Nicholas II, and on the rays are the dates "1710", "1810", "1910". Such signs had the right to wear the ranks of the crew, which were in its composition on the day of the anniversary. They were worn on the left side of the chest.

It is interesting to note that the first to whom Vandamme offered his sword was an officer of the Guards crew, Captain 2nd Rank Pavel Andreevich Kolzakov, adjutant of Grand Duke Konstantin Pavlovich. However, Pavel Andreevich first brought Vandam to the Grand Duke, and then brought him to the Sovereign.

8. Guards carriage on the way to Paris

The allies began to gather their forces to Leipzig, where the Battle of the Nations broke out on October 5-7, which decided the fate of Europe. Before that, the crew, together with the Prussian detachment, carried out an operation to destroy the bridge, which prevented the connection of enemy forces. The crew spent the days of preparation for the battle in non-stop work on the construction of crossings, as the French destroyed bridges and dams. The Battle of Leipzig finally turned the tide of hostilities in favor of the Allies. A disorderly retreat of the French troops began.

Until November 15, the crew stood in Frankfurt am Main, when he was ordered to go to Würzburg am Main, where it was necessary to build a crossing. On November 22, the crew arrived at the site and in a short time built two bridges: a floating one for artillery and cavalry, and on a goat for infantry. Before the construction of the bridges was completed, a ferry crossing was organized. Then the crew, along with the guards, proceeded to Basel and on January 1, 1814 entered France.

Napoleon, having thrown back the Silesian army of Blucher, moved on the corps of Count Wittgenstein, planning to break the allies in parts. When this became apparent, the crew was immediately sent to French city Nozhan to arrange a crossing over the Seine to ensure the withdrawal of Wittgenstein's corps. On February 6, the floating bridge, made up of river boats, was ready and the 7th Corps was transported. The sailors immediately set about destroying the crossing. Moreover, this had to be done under the fire of French soldiers. Then the crew was engaged in the crossing of the Austrian troops of Field Marshal Wrede to Saint-Louis.

Having united with the Guards Corps at the city of Troas, the crew no longer parted with it and on March 20, together with the entire guard, entered Paris, where it was stationed in the Babylon barracks in the Faubourg Saint-Germain, and the officers and non-commissioned officers - in private houses on neighboring streets.

9. Return home

When it was time to return to Russia, on May 22 the crew left Paris for Le Havre and went home on the frigate Archipelago. On July 20, all the troops were delivered from Kronstadt to Oranienbaum, and on June 30, the Naval Guards crew and its artillery team entered the capital through the Triumphal Gates, specially installed for this. On these gates is placed the name of the Guards crew, among the oldest regiments of the Imperial Guard, who distinguished themselves in the Patriotic War and on a campaign across Europe.

In connection with the return of Napoleon from the island of Elba and the resumption of hostilities, the crew was ordered to go on a campaign again. On June 9, 1815, the crew was the first to leave St. Petersburg and on August 4 arrived in Vilna. However, the battle of Waterloo finally decided the fate of Napoleon, and on August 10 the crew returned.

During the Patriotic War, the crew lost 53 sailors killed; 16 sailors were awarded the Insignia of the Military Order (St. George's Cross).

Together with the army, the crew traveled from Borodino to Paris, and was awarded the St. George Banner. However, the award high award did not affect the flags of the ships of the Guards crews.

Alexander I corrected this with his decree of June 5, 1819, which began with the words: "In memory of the battle of Kulm ...". It was announced that the distinction of the ships of the Guards crews was a tricolor pennant with the St. Andrew's flag in the head, on the center of the cross of which was superimposed a red shield with the image of George the Victorious. It was the St. George Pennant. Another difference was the St. George's Admiral's flag, which had the cloth of the St. Andrew's flag, but with the aforementioned shield in the center. This flag was designed to be hoisted on ships of the Guards crews when officials of the admiral rank were on board. Under normal conditions, all ships of the Guards crew on the stern flagpole carried the St. Andrew's flag, like all other ships of the Russian Imperial Fleet.

CONCLUSION

In conclusion, I can say that the role of the Naval Guards crew in World War II can hardly be overestimated. It was a truly unique military formation. Building bridges and crossings for other branches of the military, the sailors-guards, together with everyone else, fought, showing examples of selfless courage and endurance. The Naval Guards crew literally paved the way for their army and made it difficult for the enemy army. The uniqueness of the Marine Guards Crew was the combination of naval service on court rowing vessels, yachts and ships and coastal service as an infantry battalion of the Guards Corps of the Russian Imperial Army. In the history of the Russian fleet there will no longer be such a universal part capable of simultaneously solving such diverse and seemingly incompatible tasks.

The crew participated in almost all the wars waged by Russia. The guardsmen acted during the siege of Varna in 1828, participated in the suppression of liberation uprisings in Poland in 1831 and 1863, in the Hungarian campaign of 1849, distinguished themselves during the defense of Kronstadt in the Crimean War.

During the Russian-Turkish war of 1877-1878. sailors under the command of Grand Duke Alexei Alexandrovich fought in the Balkans. The guardsmen participated in mining on the Danube, building crossings. They were equipped with steam boats with pole mines. The boat "Tsesarevich" (commander Lieutenant F.V. Dubasov) blew up the Turkish monitor, and the boat "Joke" (commander Lieutenant N.I. Skrydlov) successfully attacked the ship. For heroism and valor in this war, the crew was awarded silver St. George's horns, and the lower ranks were awarded the wearing of St. George ribbons on caps. IN late XIX in. guards frigates "Svetlana", "Duke of Edinburgh", clipper "Shooter", corvette "Rynda" made long voyages.

The guardsmen also became famous in the Russo-Japanese war of 1904-1905. The squadron battleship "Emperor Alexander III" (commander Captain 1st Rank N.M. Bukhvostov) fought heroically in the Battle of Tsushima. Not a single sailor escaped from the ship that died, but did not lower the flag. In St. Petersburg, in the square near the St. Nicholas Naval Cathedral, a memorial obelisk was erected in honor of the sailors of the battleship. Guardsmen were completed in Vladivostok and one of the first Russian submarines "Field Marshal Count Sheremetyev".

After the Patriotic War of 1812, revolutionary sentiments spread in the Guards, and part of it participated in the Decembrist uprising. Crew officers took part in secret societies. Among them were lieutenants and midshipmen B.A. Bodisko and M.A. Bodisko, A.P. Arbuzov, A.P. Belyaev and P.P. Belyaev, V.A. Divov, N.A. Chizhov, M.K. Kuchelbecker, D.N. Lermontov, E.S. Musin-Pushkin, P.F. Miller and others. On December 14, 1825, sailors of the Guards naval crew under the command of Lieutenant Commander N.A. Bestuzhev went to Senate Square, there were 18 young officers. After the suppression of the uprising, most of them were sentenced to hard labor or sent to distant fleets, some of the sailors were exiled to the Caucasus. The guards regiments formed the core of the troops that entered the Senate Square on December 14, 1825, and four of the five executed Decembrists were guards officers.

The funds of the Central Naval Museum contain many exhibits, real relics related to the history of the Guards crew. Many of them were transferred to storage in 1918 from the Museum of the Guards Crew, which existed under him, following the example of all the oldest regiments of the Russian army. A significant part of the items is associated with the participation of the crew in the campaigns of 1812-1814: uniforms, two St. Andrew's order ribbons for the banner, commemorative badges of the crew, an album that was presented by the officers of the crew to Empress Maria Feodorovna, three paintings by the academician of battle painting I. S. Rosen , written in 1905-1910, showing the Guards crew during the stay of the Russian army in Paris in 1814, samples of cold and firearms, which was in service with the crew, as well as models of imperial yachts and ships of the time in question.

But one of the most expensive exhibits is a fragment of the St. George banner, granted to the Guards crew for courage in the battle of Kulm by the highest order of August 26, 1813, which said: “On the memorable day of the seventh on the tenth of this month, brave guards soldiers, you covered themselves with new unfading laurels, and rendered an important service to the Fatherland. You held back in small numbers and with unheard-of courage struck down the enemy, excellent in strength, who rushed with ferocity at Teplitz to extend his steps further into Bohemia ... As a token of due gratitude, I grant you: the Preobrazhensky and Semenovsky regiments and the Guards Naval crew St. George banners; St. George's trumpets to Izmailovsky and Yegersky...” A small piece of silk cloth about 30 cm long is placed in a gilded frame under glass, mounted on a board of light lacquered wood. At the bottom, a brass plate is screwed with the inscription: "PART OF THE FABRIC BANNER OF THE GUARDS CREW 1810-1910 FROM THE OLD CREW ADJUTANT". Nearby is the shaft of this banner with two silver tassels and a gilded award bracket, granted in 1838 in memory of the 25th anniversary of the Battle of Kulm. Loparev. D., Loparev, A. Naval historical reference book

Naval Guards crew and

75th naval crew

in the Patriotic War of 1812 and

Foreign campaign of the Russian army in 1813-1814.

(Nomination - Historical)

Participation in the foreign campaign of the Russian army

In the campaign of 1813, this crew worked in the construction of bridges and crossings, and where necessary, rendered them unusable.

From the first days of January, the Russian army moved after the retreating remnants of the enemy troops. Not all sailors crossed the border. 165 people remained on treatment in the cities of Russia. On January 25, the crew arrived in Plock on the Vistula. Here, by the Highest order, the Guards crew had to build a bridge and ensure the crossing of our troops, due to the almost continuous ice drift, strong wind and lack of materials, the construction of the bridge was very slow. Therefore, before the construction of the bridge, a flying ferry was introduced. Once the rope broke and the ferry with 50 hussars and horses was carried downstream. Immediately, the officers and sailors who were on the shore rushed into the boats and towed the ferry. The work was so hard that up to 40 patients appeared, some of whom died. From the first days of February to March 16, 6568 people, 1116 horses, an artillery company with 12 guns, three horse regiments, and a significant amount of other cargo were transported by boat. On March 16, the construction of the bridge came to an end and the effective crossing of troops began. The length of the bridge was 187 fathoms. The bridge was floating on 33 ships. The crossing required supervision of order and security. On April 5, the 75th ship's crew arrived, which took over supervision, and the Guards crew set out to connect with the 5th Guards Corps and the Main Apartment, which had gone ahead.

On March 27, the Headquarters and the army, located in Kalisz, moved through Silesia, the cities of Steinau, Bunzlau, Bautzen and Dresden, where they arrived on April 12. The death of the commander-in-chief was a heavy blow to our troops. Mikhail Illarionovich died in the arms of his associates, as well as the Guards crew of doctor Kerner and paramedic Galkin who were with him. The crew had the honor to say goodbye to Kutuzov when the crew passed through Bunzlau.

The army continued to move now in alliance with the Prussian troops, since an agreement on joint actions was concluded with Prussia. On May 1, the crew joined the army in Bautzen, and this time he had to meet the enemy in battle in full view of the Sovereign. By this time, Napoleon managed to gather troops that outnumbered the troops of the allies: Russia and Prussia. Napoleon's superiority in strength and his capture of fortresses on the Elbe forced the Allies to abandon the defense of Dresden and retreat to Bautzen. The position of the Allies was aggravated by their defeat in the battle of Lutzen on April 20. On May 8, Bautzen, occupied by the troops of Miloradovich, was taken by attack by the sailors of the Kompan division. The Allies fortified near Bautzen. The marine crew was part of the main reserve under the command of Grand Duke Konstantin Pavlovich. Our sailors were in the following composition: 2 staff officers, 8 chief officers, 14 non-commissioned officers, 18 musicians and 179 lower ranks. The artillery team consisted of 2 chief officers, 4 non-commissioned officers and 19 lower ranks. Total: 12 officers and 234 lower ranks.

The French launched an offensive on May 8 at 10 am. The course of the battle turned out to be unsuccessful for us and there was a proposal to retreat further, to the city of Görlitz. But Emperor Alexander I insisted on the need to continue the battle for fear of a drop in morale in the troops and the evasion of Austria from an alliance with us, with which negotiations were held.

May 9 came, a memorable day for the crew - the day of the battle on the temple regimental holiday. The relocation of the relics of St. Nicholas the Wonderworker, the patron saint of sailors, was celebrated. The crew was in the location of the main apartment, where he was on guard duty. The sovereign rode up on a horse to the ranks and said: “Hello sailors! I congratulate you on the occasion! Today is your holiday and I want to amuse you for the holiday: go to work. I will look at you." Unanimous "Hurrah!" and “Glad to try!” was the answer. The well-aimed fire of our batteries stopped the French attacks, but they, reinforced by fresh reinforcements, began to overcome. The sovereign sent a detachment of Lieutenant General Cheglokov to replace the Prussian General Count York. The detachment included the Naval Guards crew. The battalions and with them the crew stood in their positions when most of the allied troops were forced to retreat. At about 5 o'clock, Lieutenant Commander Grigory Kononovich Goremykin was killed, Lieutenant Alexander Andreevich Kolzakov was mortally wounded in the legs by a cannonball, midshipman Nikolai Petrovich Khmelev was seriously wounded. At 5 o'clock the general retreat began. The sun was already setting when it was the turn of Lieutenant General Cheglokov's battalions to retreat. The crew covered the retreat of the battalions, taking the last enemy cannonballs and grenades. Both sides suffered heavy losses. The losses of the Guards crew amounted to: 2 officers killed, 1 wounded; 6 lower ranks killed, 10 seriously wounded, as well as 4 non-commissioned officers and 5 sailors slightly wounded.

On May 23, an armistice was concluded, which ended on July 28. By this time, Napoleon's forces numbered 260 thousand people. The Allies gathered about 400 thousand people. On August 14, the allies attacked Dresden, but Napoleon inspired the besieged with his presence and the attack was repulsed. On August 15, the besieged, in turn, attacked the allied forces. Despite some success of this offensive, the French had to withdraw. The corps of the French General Vandamme was ordered to go behind the lines of the allies. On the night of August 15-16, the allied troops, fearing to be surrounded, began to retreat to Bohemia to the city of Teplitz. During the retreat, the Guards crew, with the participation of the Jaeger regiment, as well as the Preobrazhensky, Semenovsky and Izmailovsky regiments, repulsed the attacks of the French. In order to prevent Vandam's maneuver, a detachment of guard units numbering 10 thousand people was allocated, which included the Guards crew. The command of the detachment was entrusted to Lieutenant General Count Osterman-Tolstoy. Vandam's corps numbered 35 thousand people, that is, three times our strength. It was decided to stop Vandam near the village of Kulm. Napoleon promised Vandam a marshal's baton if successful. General Yermolov played an important role in organizing the defense near Kulm. Alexander I was sure that his Guard would not allow the path of the Allied army to be cut. Additionally, the Sovereign ordered that the Prussian corps of General Kleist would separate from the main forces and rush to the aid of Count Osterman-Tolstoy. The Austrian emperor, whose troops had joined after the armistice, also sent two of his corps. The guards crew was first sent to the reserve, but did not stay there for long. The guards agreed to have a certain gathering place in case they were separated - a fruit tree in a meadow. Further this place, it was decided not to retreat.

On August 17, at about 8 o'clock in the morning, French rifle chains began to descend from the mountains. Behind them flashed the bayonets of the columns of Vandam's corps. Soon there was a clash and our vanguard was forced to leave Kulm and retreat into the valley to the next position. The French twice approached the main line of defense, but the Guard repulsed the attacks. The crew operated alongside the Semenovtsy. Captain-Lieutenant Alexander Egorovich Titov was seriously wounded, the commander of the 1st company, Lieutenant Konstantin Konstantinovich Konstantinov was killed, Lieutenants Nikolai Petrovich Rimsky-Korsakov and Nikolai Petrovich Khmelev were wounded. Killed and seriously wounded up to 30 lower ranks. Repeatedly during the day, the French renewed their attacks, but to no avail. Of the officers in the crew, the commander and two officers remained. Therefore, the wounded lieutenants Dubrovin, Lermontov and Ushakov remained with the crew. Musicians, drummers and clerks took the guns of the dead and went into battle.

By the end of the day, reinforcements began to arrive. This made it possible to withdraw the guard to the reserve. The sailors gathered under the agreed fruit tree. The French, seeing a fierce rebuff, withdrew to Kulm. Thus ended the first day of the Kulm battle. It became known that the convoys that lagged behind during the accelerated march of the guard were looted, including the convoy of the Guards crew. The Prussian corps of Kleist, who was going to help, was the first to find the convoy in this form. The Prussians helped the wounded and posted guards.

Among the losses that day was also the commander of our detachment, Count Osterman-Tolstoy, whose arm was torn off. The command was taken by Major General Yermolov. The total losses of the crew that day amounted to 3/4 of the officers and more than 1/3 of the lower ranks.

On August 18, early at dawn, the main forces began to approach the Kulm position. The commander of the Russian army, Barclay de Tolly, and Yermolov, who arrived, did not start the battle, waiting for Kleist's corps to come into view. The French opened artillery fire. Around 10 o'clock it became known that Kleist was approaching. The battle began with a French cavalry charge. The infantry followed the cavalry. At first, the French bravely attacked our positions. Seeing the appearance of Kleist's troops, Vandam assumed that this was reinforcements from Napoleon. But when he recognized the Prussians and saw himself surrounded, it happened around 1 o'clock in the afternoon, then Vandamme decided to surrender. The Allies captured 12,000 Frenchmen, Vandamme and two of his generals. Two banners, three eagles were captured; all his artillery fell into the hands of the allies - 84 guns and 200 charging boxes, the entire convoy. Up to 10,000 French were killed or wounded. Our losses were also heavy. The Guards alone lost 3,000 killed and wounded in just one day on 17 August. . In this battle, the Guards crew lost 70% of the officers and more than 30% of the privates killed and wounded. The sovereign congratulated his guards on a brilliant victory. Officers and lower ranks were awarded Russian, Prussian and Austrian awards. The Marine Guards crew received the St. George banner - the highest military award on a par with the oldest regiments of the guard. The place where the victory was won is decorated with three monuments: Russian, Prussian and Austrian troops.

It is interesting to note that the first to whom Vandamme offered his sword was an officer of the Guards crew, Captain 2nd Rank Pavel Andreevich Kolzakov, adjutant of Grand Duke Konstantin Pavlovich. first brought him to the Grand Duke, and then delivered him to the Sovereign.

The allies began to gather their forces to Leipzig, where the Battle of the Nations broke out on October 5-7, which decided the fate of Europe. Before that, the crew, together with the Prussian detachment, carried out an operation to destroy the bridge, which prevented the connection of enemy forces. The crew spent the days of preparation for the battle in non-stop work on the construction of crossings, as the French destroyed bridges and dams. The Battle of Leipzig finally turned the tide of hostilities in favor of the Allies. A disorderly retreat of the French troops began.

Until November 15, the crew stood in Frankfurt am Main, when he was ordered to go to Würzburg am Main, where it was necessary to build a crossing. On November 22, the crew arrived at the site and in a short time built two bridges: a floating one for artillery and cavalry, and on a goat for infantry. Before the construction of the bridges was completed, a ferry crossing was organized. Then the crew, along with the guards, proceeded to Basel and on January 1, 1814 entered France. Rain and sleet flooded the roads, and the cavalry and artillery smashed them to the bone. Before entering France, all regiments of the guard received reinforcements. The crew, having lost many of its officers and lower ranks, remained understaffed. Therefore, a small detachment of a sapper company was attached to it, as well as a party of warriors from the militia. In this composition, the crew was able to provide an important service to our troops. Napoleon, having thrown back the Silesian army of Blucher, moved on the corps of Count Wittgenstein, intending to break the allies in parts. When this became apparent, the crew was immediately sent to the French city of Nogent to arrange a crossing over the Seine, ensuring the withdrawal of Wittgenstein's corps. On February 6, the floating bridge, made up of river boats, was ready and the 7th Corps was transported. The sailors immediately set about destroying the crossing. Moreover, this had to be done under the fire of French soldiers. After that, the crew was sent to Saint-Louis, where, as well as in Nogent, he transported the Austrian troops of Field Marshal Wrede. Having united with the Guards Corps near the city of Troas, the crew no longer parted with it and on March 20, together with the entire guard, entered Paris. In Paris, he was housed in the Babylonian barracks in the Faubourg Saint-Germain, and the officers and non-commissioned officers in private houses in the neighboring streets.

An interesting incident happened to the crew officer, now Captain 1st Rank Pavel Andreyevich Kolzakov. Even during the retreat of the French from Russia, not far from the road, Kolzakov saw a team with a fallen horse. Several Frenchmen were lying in the wagon, and between them a young officer, Kolzakov involuntarily approached the wagon and noticed that the young officer was still alive. With the help of a Cossack, the officer was transferred to the hut, where he was brought to his senses. Later, Kolzakov got him 100 chervonets for the journey when sending prisoners to Russia. After the occupation of Paris by our troops, Kolzakov fell to lodge with an old woman, from whom he learned that her only son had been saved by some naval officer. Kolzakov promised to make inquiries. The young man was found. The old woman received a notice about the return of her son from captivity and learned that her lodger was his savior.