The Patriotic War of 1812 is an important page in the history of not only our country, but also the whole of Europe. Having entered a series of “Napoleonic wars,” Russia acted as the intercessor of monarchical Europe. Thanks to Russian victories over the French, the global revolution in Europe was delayed for some time.

War between France and Russia was inevitable, and on June 12, 1812, having gathered an army of 600 thousand, Napoleon crossed the Neman and invaded Russia. The Russian army had a plan to confront Napoleon, which was developed by the Prussian military theorist Fuhl, and approved by Emperor Alexander I.

Fuhl divided the Russian armies into three groups:

- 1st commanded;

- 2nd ;

- 3rd Tormasov.

Fuhl assumed that the armies would systematically retreat to fortified positions, unite, and hold back Napoleon’s onslaught. In practice, it was a disaster. Russian troops retreated, and soon the French found themselves not far from Moscow. Fuhl's plan completely failed, despite the desperate resistance of the Russian people.

The current situation required decisive action. So, on August 20, the post of commander-in-chief was taken by one of the best students of the Great. During the war with France, Kutuzov will utter an interesting phrase: “To save Russia, we must burn Moscow.”

Russian troops will give a general battle to the French near the village of Borodino. There was a Great Slaughter, called. No one emerged victorious. The battle was brutal, with many casualties on both sides. A few days later, at the military council in Fili, Kutuzov will decide to retreat. On September 2, the French entered Moscow. Napoleon hoped that Muscovites would bring him the key to the city. No matter how it is... Deserted Moscow did not greet Napoleon solemnly at all. The city burned down, barns with food and ammunition burned down.

Entering Moscow was fatal for Napoleon. He didn't really know what to do next. The French army was harassed by partisans every day, every night. The War of 1812 was truly a Patriotic War. Confusion and vacillation began in Napoleon's Army, discipline was broken, and the soldiers began to drink. Napoleon stayed in Moscow until October 7, 1812. The French army decided to retreat south, to grain-growing regions that were not devastated by the war.

The Russian army gave battle to the French at Maloyaroslavets. The city was mired in fierce fighting, but the French wavered. Napoleon was forced to retreat along the Old Smolensk Road, the same one along which he had come. The battles near Vyazma, Krasny and at the crossing of the Berezina put an end to the Napoleonic intervention. The Russian army drove the enemy from its land. On December 23, 1812, Alexander I issued a manifesto on the end of the Patriotic War. The Patriotic War of 1812 was over, but the campaign of the Napoleonic Wars was only in full swing. The fighting continued until 1814.

The Patriotic War of 1812 is an important event in Russian History. The war caused an unprecedented surge of national self-awareness among the Russian people. Everyone, young and old, defended their Fatherland. By winning this war, the Russian people confirmed their courage and heroism, and showed an example of self-sacrifice for the good of the Motherland. The war gave us many people whose names will be forever inscribed in Russian history, these are Mikhail Kutuzov, Dokhturov, Raevsky, Tormasov, Bagration, Seslavin, Gorchakov, Barclay-De-Tolly, . And how many still unknown heroes of the Patriotic War of 1812, how many forgotten names. The Patriotic War of 1812 is a Great Event, the lessons of which should not be forgotten today.

The official cause of the war was the violation of the terms of the Tilsit Peace by Russia and France. Russia, despite the blockade of England, accepted its ships under neutral flags in its ports. France annexed the Duchy of Oldenburg to its possessions. Napoleon considered Emperor Alexander's demand for the withdrawal of troops from the Duchy of Warsaw and Prussia to be offensive. The War of 1812 was becoming inevitable.

Here is a brief summary of the Patriotic War of 1812. Napoleon, at the head of a huge 600,000-strong army, crossed the Neman on June 12, 1812. The Russian army, numbering only 240 thousand people, was forced to retreat deeper into the country. In the battle of Smolensk, Bonaparte failed to win a complete victory and defeat the united 1st and 2nd Russian armies.

In August, M.I. Kutuzov was appointed commander-in-chief. He not only had the talent of a strategist, but also enjoyed respect among soldiers and officers. He decided to give a general battle to the French near the village of Borodino. The positions for the Russian troops were chosen most successfully. The left flank was protected by flushes (earthen fortifications), and the right flank by the Koloch River. The troops of N.N. Raevsky were located in the center. and artillery.

Both sides fought desperately. The fire of 400 guns was directed at the flashes, which were courageously guarded by the troops under the command of Bagration. As a result of 8 attacks, Napoleonic troops suffered huge losses. They managed to capture Raevsky's batteries (in the center) only at about 4 o'clock in the afternoon, but not for long. The French attack was contained thanks to a bold raid by the lancers of the 1st Cavalry Corps. Despite all the difficulties of bringing the old guard, the elite troops, into battle, Napoleon never risked it. Late in the evening the battle ended. The losses were enormous. The French lost 58, and the Russians 44 thousand people. Paradoxically, both commanders declared victory in the battle.

The decision to leave Moscow was made by Kutuzov at the council in Fili on September 1. This was the only way to maintain a combat-ready army. On September 2, 1812, Napoleon entered Moscow. Waiting for a peace proposal, Napoleon stayed in the city until October 7. As a result of fires, most of Moscow was destroyed during this time. Peace with Alexander 1 was never concluded.

Kutuzov stopped 80 km away. from Moscow in the village of Tarutino. He covered Kaluga, which had large reserves of fodder and the arsenals of Tula. The Russian army, thanks to this maneuver, was able to replenish its reserves and, importantly, update its equipment. At the same time, French foraging detachments were subject to partisan attacks. The detachments of Vasilisa Kozhina, Fyodor Potapov, and Gerasim Kurin launched effective strikes, depriving the French army of the opportunity to replenish food supplies. The special detachments of A.V. Davydov also acted in the same way. and Seslavina A.N.

After leaving Moscow, Napoleon's army failed to get through to Kaluga. The French were forced to retreat along the Smolensk road, without food. Early severe frosts worsened the situation. The final defeat of the Great Army took place in the battle of the Berezina River on November 14–16, 1812. Of the 600,000-strong army, only 30,000 hungry and frozen soldiers left Russia. The manifesto on the victorious end of the Patriotic War was issued by Alexander 1 on December 25 of the same year. The victory of 1812 was complete.

In 1813 and 1814, the Russian army marched, liberating European countries from Napoleon's rule. Russian troops acted in alliance with the armies of Sweden, Austria, and Prussia. As a result, in accordance with the Treaty of Paris on May 18, 1814, Napoleon lost his throne and France returned to its 1793 borders.

Already in Moscow, this war would not turn into a brilliant victory for him, but a shameful flight from Russia the distraught soldiers of his once great army, which conquered all of Europe? In 1807, after the defeat of the Russian army in the battle with the French near Friedland, Emperor Alexander I was forced to sign the unfavorable and humiliating Treaty of Tilsit with Napoleon. At that moment, no one thought that in a few years Russian troops would drive Napoleon’s army to Paris, and Russia would take a leading position in European politics.

Classmates

Causes and course of the Patriotic War of 1812

Main reasons

- Violation by both Russia and France of the terms of the Tilsit Treaty. Russia sabotaged the continental blockade of England, which was disadvantageous for itself. France, in violation of the treaty, stationed troops in Prussia, annexing the Duchy of Oldenburg.

- The policy towards European states pursued by Napoleon without taking into account the interests of Russia.

- An indirect reason can also be considered that Bonaparte twice made attempts to marry the sisters of Alexander the First, but both times he was refused.

Since 1810, both sides have been actively pursuing preparation to war, accumulating military forces.

Beginning of the Patriotic War of 1812

Who, if not Bonaparte, who conquered Europe, could be confident in his blitzkrieg? Napoleon hoped to defeat the Russian army in border battles. Early in the morning of June 24, 1812, the Grand Army of the French crossed the Russian border in four places.

The northern flank under the command of Marshal MacDonald set out in the direction of Riga - St. Petersburg. Main a group of troops under the command of Napoleon himself advanced towards Smolensk. To the south of the main forces, the offensive was developed by the corps of Napoleon's stepson, Eugene Beauharnais. The corps of the Austrian general Karl Schwarzenberg was advancing in the Kiev direction.

The northern flank under the command of Marshal MacDonald set out in the direction of Riga - St. Petersburg. Main a group of troops under the command of Napoleon himself advanced towards Smolensk. To the south of the main forces, the offensive was developed by the corps of Napoleon's stepson, Eugene Beauharnais. The corps of the Austrian general Karl Schwarzenberg was advancing in the Kiev direction.

After crossing the border, Napoleon failed to maintain the high tempo of the offensive. It was not only the vast Russian distances and the famous Russian roads that were to blame. The local population gave the French army a slightly different reception than in Europe. Sabotage food supplies from the occupied territories became the most massive form of resistance to the invaders, but, of course, only a regular army could provide serious resistance to them.

Before joining Moscow The French army had to participate in nine major battles. In a large number of battles and armed skirmishes. Even before the occupation of Smolensk, the Great Army lost 100 thousand soldiers, but, in general, the beginning of the Patriotic War of 1812 was extremely unsuccessful for the Russian army.

On the eve of the invasion of Napoleonic army, Russian troops were dispersed in three places. Barclay de Tolly's first army was near Vilna, Bagration's second army was near Volokovysk, and Tormasov's third army was in Volyn. Strategy Napoleon's goal was to break up the Russian armies separately. Russian troops begin to retreat.

Through the efforts of the so-called Russian party, instead of Barclay de Tolly, M.I. Kutuzov was appointed to the post of commander-in-chief, with whom many generals with Russian surnames sympathized. The retreat strategy was not popular in Russian society.

However, Kutuzov continued to adhere to tactics retreat chosen by Barclay de Tolly. Napoleon sought to impose a main, general battle on the Russian army as soon as possible.

The main battles of the Patriotic War of 1812

Bloody battle for Smolensk became a rehearsal for a general battle. Bonaparte, hoping that the Russians will concentrate all their forces here, is preparing the main blow, and pulls up an army of 185 thousand to the city. Despite Bagration's objections, Baclay de Tolly decides to leave Smolensk. The French, having lost more than 20 thousand people in battle, entered the burning and destroyed city. The Russian army, despite the surrender of Smolensk, retained its combat effectiveness.

Bloody battle for Smolensk became a rehearsal for a general battle. Bonaparte, hoping that the Russians will concentrate all their forces here, is preparing the main blow, and pulls up an army of 185 thousand to the city. Despite Bagration's objections, Baclay de Tolly decides to leave Smolensk. The French, having lost more than 20 thousand people in battle, entered the burning and destroyed city. The Russian army, despite the surrender of Smolensk, retained its combat effectiveness.

The news about surrender of Smolensk overtook Kutuzov near Vyazma. Meanwhile, Napoleon advanced his army towards Moscow. Kutuzov found himself in a very serious situation. He continued his retreat, but before leaving Moscow, Kutuzov had to fight a general battle. The protracted retreat left a depressing impression on the Russian soldiers. Everyone was full of desire to give a decisive battle. When a little more than a hundred miles remained to Moscow, on a field near the village of Borodino the Great Army collided, as Bonaparte himself later admitted, with the Invincible Army.

Before the start of the battle, the Russian troops numbered 120 thousand, the French numbered 135 thousand. On the left flank of the formation of Russian troops were Semyonov’s flashes and units of the second army Bagration. On the right are the battle formations of the first army of Barclay de Tolly, and the old Smolensk road was covered by the third infantry corps of General Tuchkov.

Before the start of the battle, the Russian troops numbered 120 thousand, the French numbered 135 thousand. On the left flank of the formation of Russian troops were Semyonov’s flashes and units of the second army Bagration. On the right are the battle formations of the first army of Barclay de Tolly, and the old Smolensk road was covered by the third infantry corps of General Tuchkov.

At dawn, September 7, Napoleon inspected the positions. At seven o'clock in the morning the French batteries gave the signal to begin the battle.

The grenadiers of Major General took the brunt of the first blow Vorontsova and 27th Infantry Division Nemerovsky near the village of Semenovskaya. The French broke into Semyonov's flushes several times, but abandoned them under the pressure of Russian counterattacks. During the main counterattack here, Bagration was mortally wounded. As a result, the French managed to capture the flushes, but they did not gain any advantages. They failed to break through the left flank, and the Russians retreated in an organized manner to the Semyonov ravines, taking up a position there.

A difficult situation developed in the center, where Bonaparte’s main attack was directed, where the battery fought desperately Raevsky. To break the resistance of the battery defenders, Napoleon was already ready to bring his main reserve into battle. But this was prevented by Platov’s Cossacks and Uvarov’s cavalrymen, who, on Kutuzov’s orders, carried out a swift raid into the rear of the French left flank. This stopped the French advance on Raevsky's battery for about two hours, which allowed the Russians to bring up some reserves.

After bloody battles, the Russians retreated from Raevsky’s battery in an organized manner and again took up defensive positions. The battle, which had already lasted twelve hours, gradually subsided.

During Battle of Borodino The Russians lost almost half of their personnel, but continued to hold their positions. The Russian army lost twenty-seven of its best generals, four of them were killed, and twenty-three were wounded. The French lost about thirty thousand soldiers. Of the thirty French generals who were incapacitated, eight died.

Brief results of the Battle of Borodino:

- Napoleon was unable to defeat the Russian army and achieve the complete surrender of Russia.

- Kutuzov, although he greatly weakened Bonaparte’s army, was unable to defend Moscow.

Despite the fact that the Russians were formally unable to win, the Borodino field forever remained in Russian history as a field of Russian glory.

Having received information about losses near Borodino, Kutuzov I realized that the second battle would be disastrous for the Russian army, and Moscow would have to be abandoned. At the military council in Fili, Kutuzov insisted on the surrender of Moscow without a fight, although many generals were against it.

Having received information about losses near Borodino, Kutuzov I realized that the second battle would be disastrous for the Russian army, and Moscow would have to be abandoned. At the military council in Fili, Kutuzov insisted on the surrender of Moscow without a fight, although many generals were against it.

September 14 Russian army left Moscow. The Emperor of Europe, observing the majestic panorama of Moscow from Poklonnaya Hill, was waiting for the city delegation with the keys to the city. After the hardships and hardships of war, Bonaparte’s soldiers found long-awaited warm apartments, food and valuables in the abandoned city, which the Muscovites, who had mostly left the city with the army, did not have time to take out.

After widespread looting and looting Fires started in Moscow. Due to the dry and windy weather, the entire city was on fire. For safety reasons, Napoleon was forced to move from the Kremlin to the suburban Petrovsky Palace; on the way, he got lost and almost burned himself to death.

After widespread looting and looting Fires started in Moscow. Due to the dry and windy weather, the entire city was on fire. For safety reasons, Napoleon was forced to move from the Kremlin to the suburban Petrovsky Palace; on the way, he got lost and almost burned himself to death.

Bonaparte allowed the soldiers of his army to plunder what was not yet burned. The French army was distinguished by its defiant disdain for the local population. Marshal Davout built his bedroom in the altar of the Archangel Church. Assumption Cathedral of the Kremlin The French used it as a stable, and in Arkhangelskoye they organized an army kitchen. The oldest monastery in Moscow, St. Daniel's Monastery, was equipped for cattle slaughter.

This behavior of the French outraged the entire Russian people to the core. Everyone burned with vengeance for the desecrated shrines and the desecration of the Russian land. Now the war has finally acquired the character and content domestic.

This behavior of the French outraged the entire Russian people to the core. Everyone burned with vengeance for the desecrated shrines and the desecration of the Russian land. Now the war has finally acquired the character and content domestic.

Expulsion of the French from Russia and the end of the war

Kutuzov, withdrawing troops from Moscow, committed maneuver, thanks to which the French army had already lost the initiative before the end of the war. The Russians, retreating along the Ryazan road, were able to march onto the old Kaluga road, and entrenched themselves near the village of Tarutino, from where they were able to control all directions leading from Moscow to the south, through Kaluga.

Kutuzov foresaw that precisely Kaluga land unaffected by the war, Bonaparte will begin to retreat. The entire time Napoleon was in Moscow, the Russian army was replenished with fresh reserves. On October 18, near the village of Tarutino, Kutuzov attacked the French units of Marshal Murat. As a result of the battle, the French lost more than four thousand people and retreated. Russian losses amounted to about one and a half thousand.

Kutuzov foresaw that precisely Kaluga land unaffected by the war, Bonaparte will begin to retreat. The entire time Napoleon was in Moscow, the Russian army was replenished with fresh reserves. On October 18, near the village of Tarutino, Kutuzov attacked the French units of Marshal Murat. As a result of the battle, the French lost more than four thousand people and retreated. Russian losses amounted to about one and a half thousand.

Bonaparte realized the futility of his expectations of a peace treaty, and the very next day after the Tarutino battle he hastily left Moscow. The Grand Army now resembled a barbarian horde with plundered property. Having completed complex maneuvers on the march to Kaluga, the French entered Maloyaroslavets. On October 24, Russian troops decided to drive the French out of the city. Maloyaroslavets as a result of a stubborn battle, it changed hands eight times.

This battle became a turning point in the history of the Patriotic War of 1812. The French had to retreat along the old Smolensk road they had destroyed. Now the once Great Army considered its successful retreats as victories. Russian troops used parallel pursuit tactics. After the battle of Vyazma, and especially after the battle near the village of Krasnoye, where the losses of Bonaparte’s army were comparable to its losses at Borodino, the effectiveness of such tactics became obvious.

In the territories occupied by the French they were active partisans. Bearded peasants, armed with pitchforks and axes, suddenly appeared from the forest, which numbed the French. The element of people's war captured not only the peasants, but also all classes of Russian society. Kutuzov himself sent his son-in-law, Prince Kudashev, to the partisans, who led one of the detachments.

In the territories occupied by the French they were active partisans. Bearded peasants, armed with pitchforks and axes, suddenly appeared from the forest, which numbed the French. The element of people's war captured not only the peasants, but also all classes of Russian society. Kutuzov himself sent his son-in-law, Prince Kudashev, to the partisans, who led one of the detachments.

The last and decisive blow was dealt to Napoleon's army at the crossing Berezina River. Many Western historians consider the Berezina operation almost a triumph of Napoleon, who managed to preserve the Great Army, or rather its remnants. About 9 thousand French soldiers were able to cross the Berezina.

Napoleon, who did not lose, in fact, a single battle in Russia, lost campaign. The Great Army ceased to exist.

Results of the Patriotic War of 1812

- In the vastness of Russia, the French army was almost completely destroyed, which affected the balance of power in Europe.

- The self-awareness of all layers of Russian society has increased unusually.

- Russia, having emerged victorious from the war, strengthened its position in the geopolitical arena.

- The national liberation movement intensified in European countries conquered by Napoleon.

Research by Archpriest Alexander Ilyashenko “Dynamics of the strength and losses of the Napoleonic army in the Patriotic War of 1812.”

2012 marked two hundred years Patriotic War of 1812 And Battle of Borodino. These events are described by many contemporaries and historians. However, despite many published sources, memoirs and historical studies, there is no established point of view either for the size of the Russian army and its losses in the Battle of Borodino, or for the size and losses of the Napoleonic army. The spread of values is significant both in the number of armies and in the magnitude of losses.

In the “Military Encyclopedic Lexicon” published in St. Petersburg in 1838 and in the inscription on the Main Monument erected on the Borodino Field in 1838, it is recorded that under Borodino there were 185 thousand Napoleonic soldiers and officers against 120 thousand Russians. The monument also indicates that the losses of the Napoleonic army amounted to 60 thousand, the losses of the Russian army - 45 thousand people (according to modern data - 58 and 44 thousand, respectively).

Along with these estimates, there are others that differ radically from them.

Thus, in Bulletin No. 18 of the “Great” Army, issued immediately after the Battle of Borodino, the Emperor of France estimated French losses at only 10 thousand soldiers and officers.

The spread of estimates is clearly demonstrated by the following data.

Table 1. Estimates of opposing forces made at different times by different authors

Estimates of the sizes of opposing forces made at different times by different historians

Tab. 1

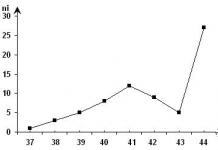

A similar picture is observed for the losses of the Napoleonic army. In the table below, the losses of the Napoleonic army are presented in ascending order.

Table 2. Losses of the Napoleonic army, according to historians and participants in the battle

Tab. 2

As we see, indeed, the spread of values is quite large and amounts to several tens of thousands of people. In Table 1, the data of the authors who considered the size of the Russian army to be superior to the size of Napoleonic's is highlighted in bold. It is interesting to note that domestic historians have joined this point of view only since 1988, i.e. since the beginning of perestroika.

The most widely used figure for the size of the Napoleonic army was 130,000, for the Russian - 120,000 people, for losses, respectively - 30,000 and 44,000.

As P.N. points out. Grunberg, starting with the work of General M.I. Bogdanovich “History of the Patriotic War of 1812 according to reliable sources,” is recognized for the reliable number of troops of the Great Army under Borodino, proposed back in the 1820s. J. de Chambray and J. Pele de Clozeau. They relied on the roll call data in Gzhatsk on September 2, 1812, but ignored the arrival of reserve units and artillery that replenished Napoleon’s army before the battle.

Many modern historians reject the data indicated on the monument, and some researchers even find it ironic. Thus, A. Vasiliev in the article “Losses of the French army at Borodino” writes that “unfortunately, in our literature about the Patriotic War of 1812 the figure 58,478 people is very often found. It was calculated by the Russian military historian V. A. Afanasyev based on data published in 1813 by order of Rostopchin. The calculations are based on information from the Swiss adventurer Alexander Schmidt, who in October 1812 defected to the Russians and pretended to be a major, allegedly serving in the personal office of Marshal Berthier.” One cannot agree with this opinion: “General Count Toll, based on official documents captured from the enemy during his flight from Russia, estimates that there are 185,000 people in the French army, and up to 1,000 artillery pieces.”

The command of the Russian army had the opportunity to rely not only on “official documents captured from the enemy during his flight from Russia,” but also on information from captured enemy generals and officers. For example, General Bonamy was captured in the Battle of Borodino. English General Robert Wilson, who was attached to the Russian army, wrote on December 30, 1812: “Among our prisoners there are at least fifty generals. Their names have been published and will undoubtedly appear in English newspapers."

These generals, as well as the captured General Staff officers, had reliable information. It can be assumed that it was on the basis of numerous documents and testimonies of captured generals and officers that, in hot pursuit, domestic military historians restored the true picture of events.

Based on the facts available to us and their numerical analysis, we tried to estimate the number of troops that Napoleon brought to the Borodino field and the losses of his army in the Battle of Borodino.

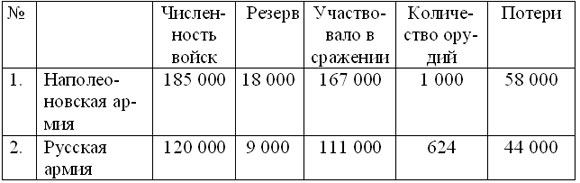

Table 3 shows the strength of both armies at the Battle of Borodino according to the widely held view. Modern domestic historians estimate the losses of the Russian army at 44 thousand soldiers and officers.

Table 3. Number of troops in the Battle of Borodino

Tab. 3

At the end of the battle, each army had reserves that did not take a direct part in it. The number of troops of both armies directly participating in the battle, equal to the difference between the total number of troops and the size of the reserves, practically coincides; in terms of artillery, the Napoleonic army was inferior to the Russian one. The losses of the Russian army are one and a half times higher than the losses of Napoleonic.

If the proposed picture corresponds to reality, then what is Borodin’s day famous for? Yes, of course, our soldiers fought bravely, but the enemy’s were braver, ours were more skillful, but they were more skillful, our commanders were experienced, and theirs were more experienced. So which army deserves more admiration? Given this balance of power, the impartial answer is obvious. If we remain impartial, we also have to admit that Napoleon won another victory.

True, there is some confusion. Of the 1,372 guns that were with the army that crossed the border, approximately a quarter were distributed to auxiliary areas. Well, of the remaining more than 1,000 guns, only a little more than half were delivered to the Borodino field?

How could Napoleon, who from a young age deeply understood the importance of artillery, allow not all the guns, but only a certain part, to be deployed for the decisive battle? Accusing Napoleon of unusual carelessness or inability to ensure the transportation of guns to the battlefield seems absurd. The question is, does the proposed picture correspond to reality and is it possible to put up with such absurdities?

Such puzzling questions are dispelled by data taken from the Monument erected on the Borodino Field.

Table 4. The number of troops in the Battle of Borodino. Monument

Tab. 4

With such a balance of forces, a completely different picture emerges. Despite the glory of the great commander, Napoleon, having one and a half superiority in forces, not only failed to crush the Russian army, but his army suffered 14,000 more losses than the Russian one. The day on which the Russian army endured the onslaught of superior enemy forces and was able to inflict losses on him that were heavier than its own is undoubtedly the day of glory of the Russian army, the day of valor, honor, and courage of its commanders, officers and soldiers.

In our opinion, the problem is of a fundamental nature. Or, using Smerdyakov’s phraseology, in the Battle of Borodino, the “smart” nation defeated the “stupid” one, or the numerous forces of Europe united by Napoleon turned out to be powerless before the greatness of spirit, courage and military art of the Russian Christ-loving army.

To better imagine the course of the war, we present data characterizing its end. The outstanding German military theorist and historian Carl Clausewitz (1780-1831), an officer of the Prussian army who served in the Russian army in the War of 1812, described these events in the book “Campaign in Russia 1812,” published in 1830 shortly before his death.

Based on Chambray, Clausewitz estimates the total number of Napoleonic armed forces that crossed the border into Russia during the campaign at 610,000.

When the remnants of the French army gathered in January 1813 across the Vistula, “they were found to number 23,000 men. The Austrian and Prussian troops returning from the campaign numbered approximately 35,000, making the total number of 58,000. Meanwhile, the created army, including the troops that subsequently arrived, actually numbered 610,000 people.

Thus, 552,000 people remained killed and captured in Russia. The army had 182,000 horses. Of these, counting the Prussian and Austrian troops and the troops of MacDonald and Rainier, 15,000 survived, therefore 167,000 were lost. The army had 1,372 guns; The Austrians, Prussians, MacDonald and Rainier brought back up to 150 guns with them, therefore, over 1,200 guns were lost.”

Let us summarize the data given by Clausewitz in a table.

Table 5. Total losses of the “Great” Army in the War of 1812

Tab. 5

Only 10% of the personnel and equipment of the army, which proudly called itself “Great,” returned back. History does not know anything like this: an army more than twice as large as its enemy was completely defeated and almost completely destroyed.

Emperor

Before proceeding directly to further research, let us touch upon the personality of the Russian Emperor Alexander I, who was subjected to a completely undeserved distortion.

The former French ambassador to Russia, Armand de Caulaincourt, a man close to Napoleon, who moved in the highest political spheres of the then Europe, recalls that on the eve of the war, in a conversation with him, the Austrian Emperor Franz said that Emperor Alexander

“they characterized him as an indecisive, suspicious and susceptible to influence sovereign; Meanwhile, in matters that could entail such enormous consequences, one must rely only on oneself and, in particular, not start a war before all means of preserving peace have been exhausted.”

That is, the Austrian emperor, who betrayed the alliance with Russia, considered the Russian emperor soft-hearted and dependent.

Many people remember the words from their school years:

The ruler is weak and crafty,

The bald dandy, the enemy of labor

He reigned over us then.

This false idea of Emperor Alexander, launched at one time by the political elite of the then Europe, was uncritically accepted by liberal Russian historians, as well as the great Pushkin, and many of his contemporaries and descendants.

The same Caulaincourt preserved de Narbonne’s story, which characterizes Emperor Alexander from a completely different perspective. De Narbonne was sent by Napoleon to Vilna, where Emperor Alexander was staying.

“Emperor Alexander frankly told him from the very beginning:

- I will not draw my sword first. I don't want Europe to hold me responsible for the blood that will be shed in this war. I have been receiving threats for 18 months. French troops are on my borders, 300 leagues from their country. I'm at my place for now. They strengthen and arm the fortresses that almost touch my borders; send troops; inciting the Poles. The emperor enriches his treasury and ruins individual unfortunate subjects. I stated that on principle I did not want to act in the same way. I don't want to take money out of my subjects' pockets to put it in my own pocket.

300 thousand French are preparing to cross my borders, and I still respect the alliance and remain faithful to all my obligations. When I change course, I will do so openly.

He (Napoleon - author) has just called Austria, Prussia and all of Europe to arms against Russia, and I am still loyal to the alliance - to such an extent my reason refuses to believe that he wants to sacrifice real benefits to the chances of this war. I have no illusions. I rate his military talents too highly not to take into account all the risks to which the lot of war may expose us; but if I have done everything to preserve an honorable peace and a political system that can lead to universal peace, then I will do nothing inconsistent with the honor of the nation over which I rule. The Russian people are not one of those who retreat in the face of danger.

If all the bayonets of Europe gather on my borders, they will not force me to speak a different language. If I was patient and restrained, it was not due to weakness, but because it is the duty of a sovereign not to listen to the voices of discontent and to have in mind only the peace and interests of his people when it comes to such large issues, and when he hopes to avoid a struggle that might cost so many victims.

Emperor Alexander told de Narbonne that at the moment he had not yet accepted any obligation contrary to the alliance, that he was confident in his rightness and in the justice of his cause and would defend himself if attacked. In conclusion, he opened a map of Russia in front of him and said, pointing to the distant outskirts:

– If Emperor Napoleon decides to go to war and fate is not favorable to our just cause, then he will have to go to the very end to achieve peace.

Then he repeated once again that he would not be the first to draw the sword, but he would be the last to sheathe it.”

Thus, Emperor Alexander, a few weeks before the outbreak of hostilities, knew that war was being prepared, that the invasion army already numbered 300 thousand people, he pursued a firm policy, guided by the honor of the nation that he ruled, knowing that “the Russian people are not those who retreat before danger." In addition, we note that the war with Napoleon is a war not only with France, but with a united Europe, since Napoleon “called Austria, Prussia and all of Europe to arms against Russia.”

There was no talk of any “treachery” or surprise. The leadership of the Russian Empire and the army command had extensive information about the enemy. On the contrary, Caulaincourt emphasizes that

“Prince Ekmulsky, the general staff and everyone else complained that they had not yet been able to obtain any information, and not a single intelligence officer had yet returned from that shore. There, on the other bank, only a few Cossack patrols were visible. The emperor reviewed the troops during the day and once again began reconnaissance of the surrounding area. The corps of our right flank knew no more about the movements of the enemy than we did. There was no information about the Russian position. Everyone complained that none of the spies were returning, which greatly irritated the emperor.”

The situation did not change with the outbreak of hostilities.

“The Neapolitan king, who commanded the vanguard, often made day marches of 10 and 12 leagues. People did not leave their saddles from three o'clock in the morning until 10 o'clock in the evening. The sun, which almost never left the sky, made the emperor forget that a day has only 24 hours. The vanguard was reinforced by carabinieri and cuirassiers; the horses, like the people, were exhausted; we lost a lot of horses; the roads were covered with horse corpses, but the emperor every day, every moment cherished the dream of overtaking the enemy. He wanted to get prisoners at any cost; this was the only way to obtain any information about the Russian army, since it could not be obtained through spies, who immediately ceased to bring us any benefit as soon as we found ourselves in Russia. The prospect of the whip and Siberia froze the ardor of the most skillful and most fearless of them; Added to this was the real difficulty of penetrating the country, and especially the army. Information was received only through Vilna. Nothing came through the direct route. Our marches were too long and too fast, and our too exhausted cavalry could not send out reconnaissance detachments or even flank patrols. Thus, the emperor most often did not know what was happening two leagues away from him. But no matter what price was attached to the capture of prisoners, it was not possible to capture them. The Cossacks' outpost was better than ours; their horses, which were better cared for than ours, turned out to be more resilient during the attack; the Cossacks attacked only when the opportunity presented itself and never got involved in battle.

At the end of the day, our horses were usually so tired that the most insignificant collision cost us several brave men, as their horses lagged behind. When our squadrons retreated, one could observe how the soldiers dismounted in the midst of the battle and pulled their horses behind them, while others were even forced to abandon their horses and flee on foot. Like everyone else, he (the emperor - author) was surprised by this retreat of the 100,000-strong army, in which not a single straggler, not a single cart, remained. For 10 leagues around it was impossible to find any horse for a guide. We had to put guides on our horses; often it was not even possible to find a person who would serve as a guide for the emperor. It happened that the same guide led us for three or four days in a row and, in the end, found himself in an area that he knew no better than us.”

While the Napoleonic army followed the Russian one, not being able to obtain even the most insignificant information about its movements, M.I. Kutuzov was appointed commander-in-chief of the army. On August 29, he “arrived at the army in Tsarevo-Zaimishche, between Gzhatsk and Vyazma, and Emperor Napoleon did not yet know about it.”

This testimony of de Caulaincourt is, in our opinion, a special praise for the unity of the Russian people, so amazing that no intelligence or enemy espionage was possible!

Now we will try to trace the dynamics of the processes that led to such an unprecedented defeat. The campaign of 1812 naturally falls into two parts: the offensive and the retreat of the French. We will only consider the first part.

According to Clausewitz, "The war is being waged in five separate theaters of war: two on the left of the road leading from Vilna to Moscow constitute the left wing, two on the right constitute the right wing, and the fifth is the huge center itself." Clausewitz further writes that:

1. Napoleonic Marshal MacDonald on the lower reaches of the Dvina with an army of 30,000 oversees the Riga garrison of 10,000 people.

2. Along the middle course of the Dvina (in the Polotsk region) first Oudinot stands with 40,000 people, and later Oudinot and Saint-Cyr with 62,000 against the Russian general Wittgenstein, whose forces first reached 15,000 people, and later 50,000.

3. In southern Lithuania, the front to the Pripyat swamps was Schwarzenberg and Rainier with 51,000 people against General Tormasov, who was later joined by Admiral Chichagov with the Moldavian army, a total of 35,000 people.

4. General Dombrovsky with his division and a small cavalry, only 10,000 people, watches Bobruisk and General Hertel, who is forming a reserve corps of 12,000 people near the city of Mozyr.

5. Finally, in the middle are the main forces of the French, numbering 300,000 people, against the two main Russian armies - Barclay and Bagration - with a force of 120,000 people; these French forces are directed towards Moscow to conquer it.

Let us summarize the data given by Clausewitz into a table and add the column “Correlation of Forces”.

Table 6. Distribution of forces by direction

Tab. 6

Having in the center more than 300,000 soldiers against 120,000 Russian regular troops (Cossack regiments are not classified as regular troops), that is, having a superiority of 185,000 people at the initial stage of the war, Napoleon sought to defeat the Russian army in a general battle. The deeper he penetrated into Russian territory, the more acute this need became. But the persecution of the Russian Army, exhausting for the center of the “Great” Army, contributed to an intensive reduction in its numbers.

The ferocity of the Borodino battle, its bloodshed, as well as the scale of losses can be judged from a fact that cannot be ignored. Domestic historians, in particular, employees of the museum on the Borodino field, estimate the number of people buried on the field at 48-50 thousand people. And in total, according to military historian General A.I. Mikhailovsky-Danilevsky, 58,521 bodies were buried or burned on the Borodino field. We can assume that the number of buried or burned bodies is equal to the number of soldiers and officers of both armies who died and died from wounds in the Battle of Borodino.

The losses of the Napoleonic army in the Battle of Borodino were widely reported by the data of the French officer Denier, who served as an inspector at Napoleon’s General Staff, presented in Table 7:

Table 7. Losses of the Napoleonic army.

Tab. 7

Denier data, rounded to 30 thousand, is currently considered the most reliable. Thus, if we accept that Denier’s data is correct, then the only casualties of the Russian army will be those killed

58,521 - 6,569 = 51,952 soldiers and officers.

This value significantly exceeds the loss of the Russian army, equal, as indicated above, to 44 thousand, including killed, wounded, and prisoners.

Denier's data is also questionable for the following reasons.

The total losses of both armies at Borodino amounted to 74 thousand, including a thousand prisoners on each side. Let us subtract the total number of prisoners from this value, and we get 72 thousand killed and wounded. In this case, the share of both armies will be only

72,000 – 58,500 = 13,500 wounded,

This means that the ratio between wounded and killed will be

13 500: 58 500 = 10: 43.

Such a small number of wounded in relation to the number of killed seems completely implausible.

We are faced with obvious contradictions with the available facts. The losses of the “Great” Army in the Battle of Borodino, equal to 30,000 people, are obviously underestimated. We cannot consider such a magnitude of losses realistic.

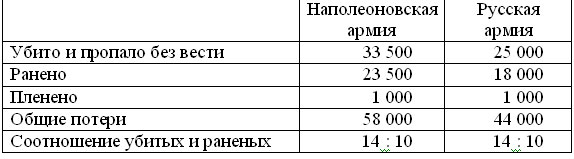

We will assume that the losses of the “Great” Army are 58,000 people. Let's estimate the number of killed and wounded in each army.

According to Table 5, which shows Denier’s data, in the Napoleonic army 6,569 were killed, 21,517 were wounded, and 1,176 officers and soldiers were captured (the number of prisoners is rounded to 1,000). About a thousand Russian soldiers were also captured. Let us subtract the number of those captured from the number of losses of each army, and we get 43,000 and 57,000 people, respectively, for a total of 100 thousand. We will assume that the number of killed is proportional to the amount of losses.

Then, in the Napoleonic army died

57,000 · 58,500 / 100,000 = 33,500,

wounded

57 000 – 33 500 = 23 500.

Died in the Russian army

58 500 - 33 500 = 25 000,

wounded

43 000 – 25 000 = 18 000.

Table 8. Losses of the Russian and Napoleonic armies

in the Battle of Borodino.

Tab. 8

We will try to find additional arguments and, with their help, justify the realistic amount of losses of the “Great” Army in the Battle of Borodino.

In further work, we relied on an interesting and very original article by I.P. Artsybashev “Losses of Napoleonic generals on September 5-7, 1812 in the Battle of Borodino.” After conducting a thorough study of the sources, I.P. Artsybashev established that in the Battle of Borodino, not 49, as is commonly believed, but 58 generals were out of action. This result is confirmed by the opinion of A. Vasiliev, who in the above article writes: “The Battle of Borodino was marked by large losses of generals: 26 generals were killed and wounded in the Russian troops, and 50 in the Napoleonic troops (according to incomplete data).

After the battles he fought, Napoleon published bulletins containing information about the size and losses of his and the enemy’s army so far from reality that in France a saying arose: “Lies like a bulletin.”

1. Austerlitz. The Emperor of France acknowledged the loss of the French: 800 killed and 1,600 wounded, for a total of 2,400 men. In fact, French losses amounted to 9,200 soldiers and officers.

2. Eylau, 58th bulletin. Napoleon ordered the publication of data on French losses: 1,900 killed and 4,000 wounded, a total of 5,900 people, while the real losses amounted to 25 thousand soldiers and officers killed and wounded.

3. Wagram. The Emperor agreed to a loss of 1,500 killed and 3,000-4,000 wounded French. Total: 4,500-5,500 soldiers and officers, but in reality 33,900.

4. Smolensk. 13th bulletin of the "Great Army". Losses: 700 French killed and 3,200 wounded. Total: 3,900 people. In fact, French losses amounted to over 12,000 people.

Let's summarize the given data in a table.

Table 9. Napoleon's bulletins

Tab. 9

The average underestimate for these four battles is 4.5, therefore it can be assumed that Napoleon underestimated the losses of his army by more than four times.

“A lie must be monstrous in order to be believed,” the Minister of Propaganda of Nazi Germany, Dr. Goebbels, once said. Looking at the table above, you have to admit that he had famous predecessors, and he had someone to learn from.

Of course, the accuracy of this estimate is not great, but since Napoleon stated that his army at Borodino lost 10,000 people, we can assume that the real losses are approximately 45,000 people. These considerations are of a qualitative nature; we will try to find more accurate estimates on the basis of which quantitative conclusions can be drawn. To do this, we will rely on the ratio of generals and soldiers of Napoleonic army.

Let's consider the well-described battles of the imperial times of 1805-1815, in which the number of Napoleonic generals who were out of action was more than 10.

Table 10. Losses of incapacitated generals and incapacitated soldiers

Tab. 10

On average, for every general who is out of action, there are 958 soldiers and officers who are out of action. This is a random variable, its variance is 86. We will proceed from the fact that in the Battle of Borodino, for every general who was incapacitated, there were 958 ± 86 soldiers and officers who were incapacitated.

958 · 58 = 55,500 people.

The variance of this quantity is equal to

86 · 58 = 5,000.

With a probability of 0.95, the true value of the losses of the Napoleonic army lies in the range from 45,500 to 65,500 people. The loss value of 30-40 thousand lies outside this interval and, therefore, is statistically insignificant and can be discarded. In contrast, the loss value of 58,000 lies within this confidence interval and can be considered significant.

As it moved deeper into the territory of the Russian Empire, the size of the “Great” Army was greatly reduced. Moreover, the main reason for this was not combat losses, but losses caused by the exhaustion of people, the lack of sufficient food, drinking water, hygiene and sanitation products and other conditions necessary to ensure the march of such a large army.

Napoleon's goal was in a rapid campaign, taking advantage of superior forces and his own outstanding military leadership, to defeat the Russian army in a general battle and dictate his terms from a position of strength. Contrary to expectations, it was not possible to force a battle because the Russian army maneuvered so skillfully and set a pace of movement that the “Great” Army could withstand with great difficulty, experiencing hardships and needing everything it needed.

The principle of “war feeds itself,” which had proven itself well in Europe, turned out to be practically inapplicable in Russia with its distances, forests, swamps and, most importantly, a rebellious population that did not want to feed the enemy army. But Napoleonic soldiers suffered not only from hunger, but also from thirst. This circumstance did not depend on the wishes of the surrounding peasants, but was an objective factor.

Firstly, unlike Europe, in Russia settlements are quite far from each other. Secondly, they have as many wells as are necessary to meet the drinking water needs of the residents, but are completely insufficient for the many soldiers passing through. Thirdly, the Russian army was ahead, whose soldiers drank these wells “to the point of mud,” as he writes in the novel “War and Peace.”

The lack of water also led to the unsatisfactory sanitary condition of the army. This entailed fatigue and exhaustion of the soldiers, caused their illnesses, as well as the death of horses. All this taken together entailed significant non-combat losses of the Napoleonic army.

We will consider the change over time in the size of the center of the “Great” Army. The table below uses Clausewitz's data on changes in army size.

Table 11. Number of “Great” Army

Tab. 11

In the “Numbers” column of this table, based on Clausewitz’s data, the number of soldiers of the center of the “Great” Army on the border, on the 52nd day near Smolensk, on the 75th near Borodin and on the 83rd at the time of entry into Moscow, is presented. To ensure the safety of the army, as Clausewitz notes, detachments were allocated to guard communications, flanks, etc. The number of soldiers in the ranks is the sum of the two previous values. As we see from the table, on the way from the border to the Borodino field, the “Great” Army lost

301,000 – 157,000 = 144,000 people,

that is, slightly less than 50% of its initial strength.

After the Battle of Borodino, the Russian army retreated, the Napoleonic army continued the pursuit. The fourth corps under the command of the Viceroy of Italy Eugene Beauharnais moved through Ruza to Zvenigorod in order to enter the retreat route of the Russian army, delay it and force it to accept a battle with Napoleon’s main forces in unfavorable conditions. The detachment of Major General F.F. sent to Zvenigorod. Winzengerode detained the viceroy's corps for six hours. Russian troops occupied a hill, resting their right flank on a ravine and their left flank on a swamp. The slope facing the enemy was a plowed field. Natural obstacles on the flanks, as well as loose soil, hampered the maneuver of enemy infantry and cavalry. The well-chosen position allowed the small detachment to “put up vigorous resistance, costing the French several thousand killed and wounded.”

We accepted that in the battle of Crimean the losses of the “Great” Army amounted to four thousand people. The rationale for this choice will be given below.

The column “Hypothetical strength” presents the number of soldiers who would remain in the ranks if there were no combat losses and security detachments would not be allocated, that is, if the army’s strength was reduced only due to the difficulties of the march. Then the hypothetical size of the army center should be a smooth, monotonically decreasing curve and it can be approximated by some function n(t).

Let us assume that the rate of change of the approximating function is directly proportional to its current value, that is

dn/dt = - λn.

Then

n(t) = n0 e- λ t ,

where n0 is the initial number of troops, n0 = 301 thousand.

The hypothetical number is related to the real one - this is the sum of the real number with the number of troops allocated for protection, as well as with the amount of losses in battles. But we must take into account that if there were no battles and the soldiers remained in the ranks, then their number would also decrease over time at the same rate as the size of the entire army. For example, if there were no battles and no guards were allocated, then in Moscow there would be

90 + (12 e- 23 λ + 30) e- 8 λ + 4 + 13 = 144.3 thousand soldiers.

The coefficients for λ are the number of days that have passed since this battle.

The parameter λ is found from the condition

Σ (n(ti) – ni)2= min, (1)

where ni are taken from the line “Hypothetical population”, ti is the number of days in a day from the moment of crossing the border.

Relative losses per day is a value characterizing the intensity of change in the hypothetical number. It is calculated as the logarithm of the ratio of the number at the beginning and end of a given period to the duration of this period. For example, for the first period:

ln(301/195.5) / 52 = 0.00830 1/day

Noteworthy is the high intensity of non-combat losses during the pursuit of the Russian army from the border to Smolensk. On the transition from Smolensk to Borodino, the intensity of losses decreases by 20%, this is obviously due to the fact that the pace of pursuit has decreased. But on the transition from Borodino to Moscow, the intensity, we emphasize, of non-combat losses increases two and a half times. The sources do not mention any epidemics that would cause increased morbidity and mortality. This once again suggests that the magnitude of the losses of the “Great” Army in the Battle of Borodino, which according to Denier is 30 thousand, is underestimated.

Let us again proceed from the fact that the strength of the “Great” Army on the Borodino field was 185 thousand, and its losses were 58 thousand. But at the same time, we are faced with a contradiction: according to Table 9, there were 130 thousand Napoleonic soldiers and officers on the Borodino field. This contradiction, in our opinion, is resolved by the following assumption.

The General Staff of Napoleonic Army recorded the number of soldiers who crossed the border with Napoleon on June 24 according to one statement, and suitable reinforcements according to another. The fact that reinforcements were coming is a fact. In a report to Emperor Alexander dated August 23 (September 4 n.s.), Kutuzov wrote: “Several officers and sixty privates were taken prisoners yesterday. Judging by the numbers of the corps to which these prisoners belong, there is no doubt that the enemy is concentrated. Subsequently, the fifth battalions of French regiments arrive to him.”

According to Clausewitz, “during the campaign, 33,000 more people arrived with Marshal Victor, 27,000 with the divisions of Durutte and Loison, and 80,000 other reinforcements, therefore about 140,000 people.” Marshal Victor and the divisions of Durutte and Loison joined the “Great” Army a long time after it left Moscow and could not participate in the Battle of Borodino.

Of course, the number of reinforcements on the march was also decreasing, so out of the 80 thousand soldiers who crossed the border, Borodin reached

185 - 130 = 55 thousand replenishments.

Then we can claim that on the Borodino field there were 130 thousand soldiers of the “Great” Army itself, as well as 55 thousand reinforcements, the presence of which remained “in the shadows”, and that the total number of Napoleonic troops should be taken equal to 185 thousand people. Let us assume that losses are proportional to the number of troops directly involved in the battle. Provided that 18 thousand remained in the reserve of the “Great” Army, the recorded losses are

58·(130 – 18) / (185 – 18) = 39 thousand.

This value coincides surprisingly well with the data of the French general Segur and a number of other researchers. We will assume that their assessment is more consistent with reality, that is, we will assume that the amount of recorded losses is 40 thousand people. In this case, the “shadow” losses will be

58 - 40 = 18 thousand people.

Consequently, we can assume that double accounting was carried out in the Napoleonic army: some of the soldiers were on one sheet, and some on another. This applies to both the total number of the army and its losses.

With the found value of the taken into account losses, condition (1) is satisfied with the value of the approximation parameter λ equal to 0.00804 1/day and the value of losses in the battle at Krymsky - 4 thousand soldiers and officers. In this case, the approximating function approximates the value of hypothetical losses with a fairly high accuracy of about 2%. This accuracy of approximation indicates the validity of the assumption that the rate of change of the approximating function is directly proportional to its current value.

Using the results obtained, we will create a new table:

Table 12. Number of the center of the “Great” Army

Tab. 12

We now see that the relative losses per day are in fairly good agreement with each other.

With λ = 0.00804 1/day, daily non-combat losses amounted to 2,400 at the beginning of the campaign and slightly more than 800 people per day as Moscow approached.

To be able to take a more detailed look at the Battle of Borodino, we proposed a numerical model of the dynamics of losses of both armies in the Battle of Borodino. A mathematical model provides additional material for analyzing whether a given set of initial conditions corresponds to reality or not, helps to discard extreme points, and also choose the most realistic option.

We assumed that the losses of one army at a given time are directly proportional to the current strength of the other. Of course, we are aware that such a model is very imperfect. It does not take into account the division of the army into infantry, cavalry and artillery, and also does not take into account such important factors as the talent of commanders, the valor and military skill of soldiers and officers, the effectiveness of command and control of troops, their equipment, etc. But, since opponents of approximately equal levels opposed each other, even such an imperfect model will give qualitatively plausible results.

Based on this assumption, we obtain a system of two first-order ordinary linear differential equations:

dx/dt = - py

dy/dt = - qx

The initial conditions are x0 and y0 – the number of armies before the battle and the amount of their losses at time t0 = 0: x’0 = - py0; y’0 = - qx0.

The battle continued until darkness, but the bloodiest actions, which brought the greatest number of losses, continued until the French captured Raevsky’s battery, then the intensity of the battle subsided. Therefore, we will assume that the active phase of the battle lasted ten hours.

By solving this system, we find the dependence of the size of each army on time, and also, knowing the losses of each army, the proportionality coefficients, i.e., the intensity with which the soldiers of one army hit the soldiers of another.

x = x0 cosh (ωt) - p y0 sinh (ωt) / ω

y = y0 cosh (ωt) - q x0 sinh (ωt) / ω,

where ω = (pq)1.

Table 7 below presents data on losses, the number of troops before the start and at the end of the battle, taken from various sources. Data on the intensity, as well as losses in the first and last hour of the battle, were obtained from the mathematical model we proposed.

When analyzing numerical data, we must proceed from the fact that the opponents confronting each other were approximately equal in training, technology and high professional level of both ordinary soldiers and officers and army commanders. But we must also take into account the fact that “Near Borodin it was a matter of whether Russia should be or not. This battle is our own, our native battle. In this sacred lottery we were investors in everything inseparable from our political existence: all our past glory, all our present national honor, national pride, the greatness of the Russian name - all our future destiny.”

During a fierce battle with a numerically superior enemy, the Russian army retreated somewhat, maintaining order, control, artillery and combat effectiveness. The attacking side suffers greater losses than the defending side until it defeats its enemy and he takes flight. But the Russian army did not flinch and did not run.

This circumstance gives us reason to believe that the total losses of the Russian army should be less than the losses of the Napoleonic army. It is impossible not to take into account such an intangible factor as the spirit of the army, to which the great Russian commanders attached so much importance, and which Leo Tolstoy so subtly noted. It is expressed in valor, perseverance, and the ability to defeat the enemy. We can, of course, conditionally assume that this factor in our model is reflected in the intensity with which warriors of one army hit warriors of another.

Table 13. Number of troops and losses of the parties

Tab. 13

The first line of Table 13 shows the initial strength and casualty figures reported in Napoleon's Grand Army Bulletin No. 18. With this ratio of the initial number and the magnitude of losses, according to our model, it turns out that during the battle the losses of the Russian army would have been 3-4 times higher than the losses of the Napoleonic army, and the Napoleonic soldiers fought 3 times more effectively than the Russians. With such a course of the battle, it would seem that the Russian army should have been defeated, but this did not happen. Therefore, this initial data set is not true and should be rejected.

The next line presents the results based on data from the French professors Lavisse and Rambaud. As our model shows, the losses of the Russian army would be almost three and a half times greater than the losses of Napoleonic. In the last hour of the battle, the Napoleonic army would lose less than 2% of its strength, and the Russian army - more than 12%.

The question is, why did Napoleon stop the battle if the Russian army was soon expected to be defeated? This is contradicted by eyewitness accounts. We present Caulaincourt's testimony about the events that followed the capture of Raevsky's battery by the French, as a result of which the Russian army was forced to retreat.

“A sparse forest covered their passage and hid their movements in this place from us. The emperor hoped that the Russians would speed up their retreat, and hoped to throw his cavalry at them to try to break the line of enemy troops. Units of the Young Guard and the Poles were already moving to approach the fortifications that remained in Russian hands. The Emperor, in order to better examine their movements, went forward and walked right up to the very line of riflemen. Bullets whistled around him; he left his retinue behind. The emperor was at that moment in great danger, since the firing became so hot that the Neapolitan king and several generals rushed to persuade and beg the emperor to leave.

The emperor then went to the approaching columns. The old guard followed him; carabinieri and cavalry marched in echelons. The emperor, apparently, decided to capture the last enemy fortifications, but the Prince of Neuchâtel and the King of Naples pointed out to him that these troops did not have a commander, that almost all divisions and many regiments also lost their commanders who were killed or wounded; the number of cavalry and infantry regiments, as the emperor can see, has greatly decreased; the time is already late; the enemy is indeed retreating, but in such an order, maneuvers in such a way and defends the position with such courage, although our artillery crushes his military masses, that one cannot hope for success unless the old guard is allowed to attack; in such a state of affairs, success achieved at this cost would be a failure, and failure would be such a loss that would cross out the gain of the battle; finally, they drew the emperor’s attention to the fact that they should not risk the only corps that still remained intact, and should save it for other occasions. The Emperor hesitated. He rode forward again to observe the enemy’s movements himself.”

The emperor “made sure that the Russians were taking up positions, and that many corps not only did not retreat, but were concentrating together and, apparently, were going to cover the retreat of the remaining troops. All the reports that followed one after another said that our losses were very significant. The Emperor made a decision. He canceled the order to attack and limited himself to an order to support the corps still fighting in case the enemy tried to do something, which was unlikely, because he also suffered enormous losses. The battle ended only at nightfall. Both sides were so tired that at many points the shooting stopped without a command.”

The third line contains the data of General Mikhnevich. The very high level of losses of the Russian army is striking. No army, not even a Russian one, can withstand the loss of more than half of its initial strength. In addition, estimates by modern researchers agree that the Russian army lost 44 thousand people in the battle. Therefore, these initial data do not seem to correspond to reality and should be discarded.

Let's look at the data in the fourth row. With such a balance of forces, our proposed model shows that Napoleonic army fought extremely effectively and inflicted heavy losses on its enemy. Our model allows us to consider some possible situations. If the number of armies were the same, then with the same efficiency, the number of the Russian army would be reduced by 40%, and the Napoleonic army by 20%. But the facts contradict such assumptions. In the battle of Maloyaroslavets, the forces were equal, and for the Napoleonic army it was not about victory, but about life. However, Napoleon's army was forced to retreat and return to the devastated Smolensk road, dooming itself to hunger and hardship. In addition, we showed above that the amount of losses equal to 30 thousand is underestimated, therefore Vasiliev’s data should be excluded from consideration.

According to the data given in the fifth line, the relative losses of the Napoleonic army, amounting to 43%, exceed the relative losses of the Russian army, equal to 37%. It cannot be expected that European soldiers, who fought for winter quarters and the opportunity to profit from the plunder of a defeated country, could withstand such high relative losses, exceeding the relative losses of the Russian army, which fought for its Fatherland and defended the Orthodox Faith from the atheists. Therefore, although these data are based on the ideas of modern domestic scientists, nevertheless, they seem unacceptable to us.

Let's move on to consider the data in the sixth line: the strength of the Napoleonic army is assumed to be 185 thousand, the Russian army - 120 thousand, losses - 58 and 44 thousand people. According to the model we have proposed, the losses of the Russian army throughout the battle are somewhat lower than the losses of the Napoleonic army. Let us pay attention to an important detail. The efficiency with which Russian soldiers fought was twice that of their opponents! The late veteran of the Great Patriotic War, when asked: “What is war?”, answered: “War is work, hard, dangerous work, and it must be done faster and better than the enemy.” This is quite consistent with the words of the famous poem by M.Yu. Lermontov:

The enemy experienced a lot that day,

What does Russian fighting mean?

Our hand-to-hand combat!

This gives us reason to understand why Napoleon did not send the guard into the fire. The valiant Russian army fought more effectively than its enemy and, despite the inequality of forces, inflicted heavier losses on him. It is also impossible not to take into account the fact that the losses in the last hour of the battle were almost identical. Under such conditions, Napoleon could not count on the defeat of the Russian army, just as he could not exhaust the strength of his army in what had become a futile battle. The results of the analysis allow us to accept the data presented in the sixth row of Table 13.

So, the number of the Russian army was 120 thousand people, the Napoleonic army was 185 thousand, respectively, the losses of the Russian army were 44 thousand, the Napoleonic army was 58 thousand.

Now we can create the final table.

Table 14. Number and losses of the Russian and Napoleonic armies

in the Battle of Borodino.

Tab. 14

The valor, selflessness, and military skill of the Russian generals, officers and soldiers, who inflicted huge losses on the “Great” Army, forced Napoleon to abandon the decision to introduce his last reserve - the Guards Corps - at the end of the battle, since even the Guard might not achieve decisive success. He did not expect to meet such exceptionally skillful and fierce resistance from Russian soldiers, because

And we promised to die

And they kept the oath of allegiance

We are at the Battle of Borodino.

At the end of the battle, M.I. Kutuzov wrote to Alexander I: “This day will remain an eternal monument to the courage and excellent courage of the Russian soldiers, where all the infantry, cavalry and artillery fought desperately. Everyone’s desire was to die on the spot and not yield to the enemy. The French army, led by Napoleon himself, being in superior strength, did not overcome the fortitude of the Russian soldier, who cheerfully sacrificed his life for his fatherland.”

Everyone cheerfully sacrificed their lives for their fatherland, from soldiers to generals.

“Confirm in all companies,” artillery chief Kutaisov wrote to Borodin the day before, “that they do not move from their positions until the enemy sits astride the guns. To tell the commanders and all gentlemen officers that only by courageously holding on to the closest shot of grapeshot can we ensure that the enemy does not yield a single step of our position.

Artillery must sacrifice itself. Let them take you with the guns, but fire the last canister shot at point-blank range... Even if the battery had been taken after all this, although one can almost guarantee otherwise, then it would have already fully atoned for the loss of the guns...”

It should be noted that these were not empty words: General Kutaisov himself died in the battle, and the French were able to capture only a dozen guns.

Napoleon's task in the Battle of Borodino, as well as at the stage of pursuit, was the complete defeat of the Russian army, its destruction. To defeat an enemy of approximately equal military skill, a large numerical superiority is required. Napoleon concentrated 300 thousand in the main direction against the Russian army of 120 thousand. Possessing a superiority of 180 thousand at the initial stage, Napoleon was unable to maintain it. “With more care and better organization of the food supply, with a more deliberate organization of marches, in which huge masses of troops would not be uselessly piled up on one road, he could have prevented the famine that reigned in his army from the very beginning of the campaign, and thereby preserving it in a more complete composition."

Huge non-combat losses, indicating a disregard for his own soldiers, who for Napoleon were just “cannon fodder,” were the reason that in the Battle of Borodino, although he had one and a half superiority, he lacked one or two corps to deliver a decisive blow . Napoleon was unable to achieve his main goal - the defeat and destruction of the Russian army, either at the stage of pursuit or in the Battle of Borodino. The failure to complete the tasks facing Napoleon is an indisputable achievement of the Russian army, which, thanks to the skill of command, courage and valor of officers and soldiers, snatched success from the enemy in the first stage of the war, which was the reason for his heavy defeat and complete defeat.

“Of all my battles, the most terrible is the one I fought near Moscow. The French showed themselves worthy of victory, and the Russians acquired the right to be invincible,” Napoleon later wrote.

As for the Russian army, during the most difficult, brilliantly executed strategic retreat, in which not a single rearguard battle was lost, it retained its strength. The tasks that Kutuzov set for himself in the Battle of Borodino - to preserve his army, to bleed and exhaust Napoleon's army - were equally brilliantly accomplished.

On the Borodino field, the Russian army withstood the army of Europe united by Napoleon, one and a half times larger in number, and inflicted significant losses on its enemy. Yes, indeed, the battle near Moscow was “the most terrible” of those that Napoleon fought, and he himself admitted that “the Russians have acquired the right to be invincible.” One cannot but agree with this assessment of the Emperor of France.

Notes:

1 Military encyclopedic lexicon. Part two. St. Petersburg 1838. pp. 435-445.

2 P.A. Zhilin. M. Science. 1988, p. 170.

3 Battle of Borodino from Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia. We have corrected errors in the 4th and 15th lines, in which the compilers rearranged the numbers of the Russian and Napoleonic armies.

4 Artsybashev I.P. Losses of Napoleonic generals on September 5-7, 1812 in the Battle of Borodino.

5 Grunberg P.N. On the size of the Great Army in the Battle of Borodino // The era of the Napoleonic wars: people, events, ideas. Materials of the V All-Russian Scientific Conference. Moscow April 25, 2002 M. 2002. P. 45-71.

6A. Vasiliev. “Losses of the French army at Borodino” “Motherland”, No. 6/7, 1992. P.68-71.

7 Military encyclopedic lexicon. Part two. St. Petersburg 1838. P. 438

8 Robert Wilson. “Diary of travel, service and social events during his time with the European armies during the campaigns of 1812-1813. St. Petersburg 1995 p. 108.

9 According to Chambray, from whom we generally borrowed data on the size of the French armed forces, we determined the size of the French army at its entry into Russia at 440,000 people. During the campaign, 33,000 more people arrived with Marshal Victor, 27,000 with the divisions of Durutte and Loison, and 80,000 other reinforcements, therefore, about 140,000 people. The rest consists of convoy parts. (Note by Clausewitz). Clausewitz. Campaign in Russia in 1812. Moscow. 1997, p. 153.

10 Clausewitz. Campaign in Russia in 1812. Moscow. 1997, p. 153.

11 Armand de Caulaincourt. Memoirs. Smolensk 1991. P.69.

12 Armand de Caulaincourt. Memoirs. Smolensk 1991. P. 70.

13 Armand de Caulaincourt. Memoirs. Smolensk 1991. P. 77.

14 Armand de Caulaincourt. Memoirs. Smolensk 1991. pp. 177,178.

15 Armand de Caulaincourt. Memoirs. Smolensk 1991. P. 178.

16 Clausewitz. 1812 Moscow. 1997, p. 127.

17 “Motherland”, No. 2, 2005.

18 http://ukus.com.ua/ukus/works/view/63

19 Clausewitz. Campaign in Russia in 1812. Moscow. 1997 p. 137-138.

20 M.I. Kutuzov. Letters, notes. Moscow. 1989 p. 320.

21 Denis Davydov. Library for reading, 1835, vol. 12.

22 E. Lavisse, A. Rambaud, “History of the 19th century,” M. 1938, vol. 2, p. 265

23 “Patriotic War and Russian Society.” Volume IV.

24 A. Vasiliev. “Losses of the French army at Borodino” “Motherland”, No. 6/7, 1992. P.68-71.

25 P.A. Zhilin. M. Science. 1988, p. 170.

26 Armand de Caulaincourt. Memoirs. Smolensk 1991. pp. 128,129.

27 M.I. Kutuzov. Letters, notes. Moscow. 1989 p. 336

28 M. Bragin. Kutuzov. ZhZL. M. 1995. p.116.

29 Clausewitz. 1812 Moscow. 1997, p. 122.

The cause of the war was the violation by Russia and France of the terms of the Tilsit Treaty. Russia actually abandoned the blockade of England, accepting ships with British goods under neutral flags in its ports. France annexed the Duchy of Oldenburg, and Napoleon considered the demand for the withdrawal of French troops from Prussia and the Duchy of Warsaw offensive. A military clash between the two great powers was becoming inevitable.