On November 6, 1796, Emperor Paul I (1754-1801) ascended the Russian throne. He ruled in 1796-1801, and at the same time proved himself to be a rude, despotic and unjustifiably cruel ruler. All this time, society was in a state of fear and confusion. Eventually, a conspiracy arose among the guard and high society. It ended with a palace coup and the assassination of Paul I.

Emperor Paul I with family members

Artist Gerard von Kügelgen

The future sovereign was born on September 20, 1754 in the Summer Palace of St. Petersburg in the family of the heir to the throne, Peter Fedorovich and Ekaterina Alekseevna. Immediately after birth, he was taken away from his parents by Empress Elizaveta Petrovna, as she wished to raise her grandson herself.

He grew up as a developed but shy boy. He was inclined to chivalrous deeds, noble impulses and had a high idea of serving the Fatherland. However, the life of the crown prince could not be called easy. His relationship with his mother Catherine II can be described as rather complex.

The mother herself did not feel any feelings for her son. good feelings, because she gave birth to him from an unloved husband. Paul was humiliated by the empress's favorites, the young man suffered from palace intrigues and his mother's spies. He was not allowed near state affairs, and gradually the young man became bilious and suspicious of those around him.

In 1773, the future emperor was married to Wilhelmina of Hesse-Darmstadt (1755-1776). The bride converted to Orthodoxy, and they began to call her Natalya Alekseevna. 2.5 years passed, and the wife died during childbirth along with the baby.

But the second marriage with Sophia Dorothea of Württemberg (1759-1828) in 1776 turned out to be successful. After accepting Orthodoxy, the bride was named Maria Feodorovna. She was a beautiful and stately girl. She bore her husband 10 children. Two of them - Alexander and Nicholas - became emperors in the future.

Until the age of 42, Pavel remained out of work. Over the years, his youthful impulses and dreams of universal happiness and justice faded away. And their place was taken by suspicion, anger, the desire to put an end to Catherine’s depraved court and force everyone to serve and obey unquestioningly.

The future sovereign embodied these ideas in his Gatchina estate. The Empress gave it to her son in 1783. Before this, the estate belonged to Catherine’s favorite Grigory Orlov, but he died, and Pavel became the owner. Here, surrounded by devoted and faithful people, he felt completely safe.

A small regular army was created on the Prussian model with iron discipline. Very soon this military unit became the best in Russian army. The customs and orders established on the estate were sharply different from everything that existed at that time in the empire. Subsequently, all this began to be implemented nationwide, when the heir to the throne received power.

Reign of Paul I (1796-1801)

In the fall of 1796, Catherine II died. Her son, Emperor Paul I, ascended the throne. The coronation of the sovereign and empress took place on April 5, 1797. In history Russian state this was the first time that husband and wife were crowned at the same time. On this solemn day, the sovereign read out the decree on succession to the throne. According to it, women were removed from power, and thus, women's rule in Russia ended.

The new ruler was a staunch opponent of his mother’s methods of rule, and intolerance towards the old order appeared already in the first days of his reign. This was expressed in an uncompromising struggle against the old foundations in the army, guard and state apparatus. Discipline intensified, service became strict, and punishments became severe even for minor offenses.

The streets of St. Petersburg have changed dramatically. Booths painted with black and white stripes appeared everywhere. The police began to grab passers-by and drag them to the station if they ignored the imperial prohibitions on wearing certain types of clothing. For example, round French hats were banned.

The entire army was dressed in new uniforms. Soldiers and officers began to master the new Prussian order that had previously reigned in Gatchina. The spirit of the military began to hover over the capital. In 1798, corporal punishment for nobles, previously abolished by Catherine II, was reintroduced. Now any nobleman could be deprived of his rank overnight, subjected to humiliating punishment, or sent to Siberia.

Residents of St. Petersburg, waking up every morning, expected to hear some new amazing decree. The import of any books from abroad, no matter what language they were written in, was prohibited. In 1800, a decree was issued prohibiting clapping in the theater until the sovereign himself clapped. A decree was also issued banning the word “snub-nosed.” The point here is that the emperor’s nose was really snub-nosed.

Foreign policy was no less extravagant. In 1798, military treaties were concluded with England, the worst enemy of Turkey and Austria against France. Alexander Vasilyevich Suvorov, who had previously been in disgrace, was appointed commander-in-chief of the Russian army. He stood at the head of the Russian-Austrian troops and won victories over the French on the Trebia, Adda and Novi rivers. In 1799, the Russian army under the command of Suvorov made an unprecedented crossing of the Alps.

The transition of the Russian army under the command of Suvorov through the Alps

In the autumn of the same year Russian Empire broke the alliance with Austria due to the Austrians' failure to fulfill some allied obligations. As a result of this, Russian troops were withdrawn from Europe. The Anglo-Russian expedition to the Netherlands ended in failure.

At sea, the Russian squadron was commanded by Admiral Ushakov. In the Mediterranean, he successfully expelled the French from the Ionian archipelago. But then the alliance with England was dissolved, and Russia began to move closer to Napoleon Bonaparte, who came to power in France. As a result of this, preparations began for a joint campaign of Russian and French troops in India, which was under English rule.

Regarding architecture, to which all sovereigns and empresses were not indifferent, then under Emperor Paul I the most noticeable construction project was the construction Mikhailovsky Castle. It was in this creation that the All-Russian autocrat tried to embody his views on architecture. They were based on romantic ideas about knightly castles of the Middle Ages and on the desire to create something completely different from the palaces of Catherine’s era.

The site where Elizabeth Petrovna's Summer Palace stood was chosen for construction. It was demolished and the Mikhailovsky Castle was erected. Construction work began in 1797 and lasted less than 4 years. A vast parade ground was created in front of the castle, and in the middle, K. B. Rastrelli sculpted a monument to Peter the Great.

Everything turned out exactly as the young Paul himself once wrote: “Despotism first absorbs everything around itself, and then destroys the despot himself.” As a result of a palace coup, Emperor Alexander I came to power.

Leonid Druzhnikov

“Thank God we are legit!”

/Published in "Russian Word", Prague

/

They say that in 1754, the courtiers of the Russian imperial court were whispering about which middle name would be more suitable for the newborn Paul, the son of Grand Duchess Catherine - Petrovich or Sergeevich? Later this rumor turned into a question whether Pavel was interrupted I Romanov bloodline? This can be answered quite definitely - no, she was not interrupted. But the history of the dynasty definitely bent into the realm of fantasy and fiction.

There is a funny historical anecdote: as if Alexander III ordered Pobedonostsev, his teacher and respected adviser, to check the rumor that the father of Paul I was not Peter III, but Sergei Vasilyevich Saltykov, the first lover of the future Empress Catherine II. Pobedonostsev first informed the emperor that, in fact, Saltykov could be the father. Alexander III rejoiced: “Thank God, we are Russian!” But then Pobedonostsev found facts in favor of Peter’s paternity. The emperor, however, rejoiced again: “Thank God, we are legal!”

The moral, if it can be deduced from the joke at all, is simple: the nature of power is not in the blood, but in the ability and desire to rule, the rest can be adapted to this. At least, this is the nature of imperial power - every empire brings with it a huge number of unresolved contradictions, one more is no big deal.

However, how could this plot and with it numerous variations on this theme arise? Oddly enough, it was largely created by Catherine II. In her “Notes,” she writes about the beginning of her romance with Saltykov in the spring of 1752: “During one of these concerts (at the Choglokovs), Sergei Saltykov made me understand the reason for his frequent visits. I didn’t answer him right away; when he again began to talk to me about the same thing, I asked him: what does he hope for? Then he began to draw me as captivating as full of passion a picture of the happiness he was counting on..."

Next, all stages of the novel are described in detail, down to the rather intimate ones - rapprochement in the fall of 1752, pregnancy, which ended in a miscarriage on the way to Moscow in December, a new pregnancy and miscarriage in May 1753, the cooling of the lover, which made Catherine suffer, strict supervision established for Grand Duchess in April 1754, which meant the removal of Sergei Saltykov. And Pavel, as you know, was born on September 24, 1754. Peter is mentioned in this chapter of the notes only in connection with his drunkenness, courtship of Catherine’s ladies-in-waiting and other ladies, as well as the suspicions that arose in him regarding Sergei Saltykov. From this whole story it follows that Saltykov could be Pavel’s father. Moreover, the author of the Notes creates this impression deliberately.

However, Catherine does not have to be particularly trusted. After all, she had to justify her seizure of power in various ways. After her husband's overthrow, she created so many stories about him and their relationship that historians trying to sort out what is true and what is not will have their work cut out for a long time. (What is, say, Catherine’s fable about a rat allegedly condemned and hanged by Peter on the gallows, having eaten two of his toy soldiers. It’s impossible to hang a rat like a human. The rat’s neck is too powerful for this. And the rope will slip off it. The story is insignificant, and come on, historiographers since the time of S. Solovyov have trustingly repeated it again and again.).

So this story requires an investigation of the motives of Catherine, who for some reason casts a shadow on her own son.

According to historian S. Mylnikov, author of a book about Peter III, Catherine was afraid of potential supporters of Paul, who could demand the throne for a ruler with royal blood in exchange for a foreigner who had usurped power and had no right to it. Before the coup, a proposal was made (by N. Panin, Paul’s mentor) to declare Catherine not an empress, but a regent of the young heir until he came of age. Although it was rejected, it was not completely forgotten.

The empress's move was quite logical from the point of view of political struggle - she once again told her opponents that Paul did not have this blood - not a drop! And she has no more rights to the throne than her mother. But perhaps Catherine was motivated by other considerations. Maybe she once again put herself, her needs, desires and talents in the foreground instead of some kind of royal blood that created a husband she despised and, in general, worthless.

And S. Mylnikov convincingly proves that Peter III certainly considered Paul his son. He compares the notice of the birth of his son, which he sent to Frederick II, with a similar notice of the birth of his daughter Anna, which was definitely from Catherine’s next lover, Stanislav Poniatowski, which Peter knew about. Indeed, the difference between the two letters is great.

Another historian, N. Pavlenko, holds a different point of view. He writes: “Other courtiers who observed family life of the grand ducal couple, they whispered that the baby should be called Sergeevich, not Petrovich, according to his father. That's probably what happened."

So who should you believe? Petra? Catherine's hints? To the long-lost whispers of the courtiers? Perhaps these paths are already too well-trodden and will not yield anything new.

I wonder what materials Pobedonostsev used. Aren't they portraits of participants in history? After all, facial features are inherited and belong to one of the parents - this was known even before the advent of genetics as a science. We can also do a little analysis using portraits.

They are before us - the “freak” (as Empress Elizabeth called her nephew in anger) Peter, the handsome Sergei and the loving Catherine. The latter recalled her young self as follows: “They said that I was as beautiful as day and amazingly good; To tell the truth, I never considered myself extremely beautiful, but I was liked, and I believe that this was my strength.” The Frenchman Favier, who saw Catherine in 1760 (she was then 31 years old), subjected her appearance to a rather harsh assessment: “It’s impossible to say that her beauty is dazzling: a rather long, in no way flexible waist, noble posture, but her gait is cutesy, not graceful.” ; the chest is narrow, the face is long, especially the chin; a constant smile on the lips, but the mouth is flat, depressed; the nose is somewhat hunched; small eyes, but a lively, pleasant look; traces of smallpox are visible on the face. She is more beautiful than ugly, but you can’t get carried away with her.”

These and other assessments can be found in N. Pavlenko’s book “Catherine the Great”. Interesting in themselves, they confirm the correspondence of the descriptions and the portrait, we can use it with complete confidence.

Sergei Vasilyevich Saltykov is also long-faced, his facial features are proportional, his eyes are almond-shaped, his lips are small and elegant, his forehead is high, his nose is straight and long. Catherine wrote about him: “he was as beautiful as day, and, of course, no one could compare with him in any way.” big yard, and especially not with ours. He had no lack of intelligence, nor of that store of knowledge, manners and techniques that great society and especially the court provide.”

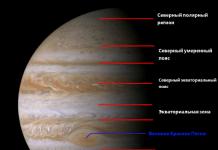

Peter III Catherine Sergei Saltykov

Paul I (child portrait) Paul I adult (graphic sketch)

Rice. 1. “Parents” and son (fragments of portraits were used).

In comparison with them, Pyotr Fedorovich, of course, is catastrophically inferior in appearance - and is distinguished by a number of traits that only he could leave to his descendant. His face is quite round, even cheekbones. The forehead is sloping, the nose is shorter than that of Ekaterina and Sergei Saltykov, very wide at the bridge of the nose, the mouth is large, the eyes are narrow and set wide apart. And he was also ticklish.

Portraits of Paul show a clear resemblance to Peter. Especially adult portraits. The same face shape, sloping forehead, large mouth, short nose - even remembering the possibility of the existence of recessive traits, Saltykov and Ekaterina (both “beautiful as day”) of such an ugly descendant, whom Admiral Chichagov called “a snub-nosed Chukhon with the movements of a machine gun,” would not have done it. If Pavel’s father had been Sergei Saltykov, the shape of the face and forehead would have been different, the lips and nose would have been different - since Catherine and Saltykov had them similar, sharply different from Peter’s features. And, one must think, the character would have been different. There are so many features of Peter in Pavel’s face that you don’t even need a DNA test to say definitely - yes, Sergei Saltykov was not Pavel’s father. It was Peter III.

By the way, by the date of birth it is clear that the heir turned out to be a typical fruit of the holidays - so Catherine remembers that she celebrated New Year the empress - of course, with her husband. Apparently, that night, after the celebration, the future Paul was conceived.

The opinion of S. Mylnikov is confirmed that Saltykov’s paternity was deliberately played up by Ekaterina. There is no doubt who her son's real father was - she knew very well. Probably for this reason she behaved extremely coldly towards Pavel. As a child, she quietly left him in the care of nannies and did not see him for weeks. She wanted to force her already adult son to renounce his right to the throne in favor of his grandson, Alexander.

This little story once again confirms the description given to Catherine by the historian Ya. Barskov: “Lies were the queen’s main tool: all her life, from early childhood to old age, she used this tool, wielded it like a virtuoso, and deceived her parents, lovers, and subjects. , foreigners, contemporaries and descendants." The records of Catherine’s lies were her stories about the situation of Russian peasants: “Our taxes are so light that there is not a man in Russia who does not have a chicken whenever he wants, and for some time they have preferred turkeys to chickens” (letter to Voltaire, 1769) and “It used to happen before, driving through villages, you would see little children in only a shirt, running barefoot in the snow; Now there is not a single one who does not have an outer dress, a sheepskin coat and boots. Although the houses are still wooden, they have expanded and most of them are on two floors” (letter to Bjelke, a friend of his mother, 1774). Peasants living in two-story huts, with children dressed in sheepskin coats and boots, preferring turkeys to chickens - there is, of course, an almost Manila dream in this and not only an element of deception, but also self-deception.

It was he who added to Pavel’s two fathers a third contender, Emelyan Pugachev. It must be said that it is an amazing irony of history: one future emperor has three fathers. The phantom Potemkin villages for which his mother's reign became famous. The phantasmagoria of his own reign with the non-existent but career-making lieutenant Kizhe (even though this is Tynyanov’s fiction, it is, as they say, completely authentic). A parricide son who either died in Taganrog or in Siberia. Everything seems to be imbued with that original fantasy of Catherine. Indeed, lies have long legs.

But what could Catherine do? Her role was that of a tightrope walker. Those who, in those daring times, did not understand that power had to be shared with a fairly wide circle, ended badly - take, for example, Catherine’s husband and son. The Empress, with her big plans, will and efficiency, was not the worst of the Russian monarchs based on the results of her reign. But she had to give up most of her good aspirations. One should also not attribute the merits of Russia at that time to her alone - the people with whom she had to get along and trust important posts were no less responsible for the country’s successes.

However, the government, which must constantly resort to lies and create illusions, causes skepticism. While acting well in the external sphere, Catherine turned out to be decidedly weak in solving internal problems. Having given the imperial frame created by Peter the Great an external shine, she was unable to do anything with negative sides his reforms. So we had to turn a blind eye to the state of the country, deceive and be deceived.

AND Catherine II. Future All-Russian Emperor raised by nannies and teachers Elizaveta Petrovna and was removed from his parents. This was the first reason for Pavel’s bad relationship with his mother, Catherine the Great. In addition, little Pasha accused his mother of losing his father, and until the end of his life he could not forgive her for his death.

Domestic policy.

First of all, after the crowning in April 1797, Paul I issued a new decree on succession to the throne. Only a descendant in the male line could become the heir to the throne. The exception was the case if there were no heirs, but only heiresses Romanov dynasty .

In 1796, even before the law on succession to the throne, he reformed the Senate, and later, in 1797, he brought the reform to fruition, restoring State Council (which under Catherine I did not fulfill its functions), and created new rules in the work of the Senate. Unlike Catherine, Paul I sought to improve the situation with the peasants, which caused dissatisfaction among the nobility. Especially after the emperor canceled the charter of the noble nobility. Nobles were again required to serve in the army, this time for at least a year.

Paul's military reforms were even more stringent - he sought to transform the army following the example of the Prussian king Frederick. In this he displeased even the prince Alexandra Suvorova, although not for long.

Foreign policy.

In 1792, a revolution occurred in France, and Russia's relations with it deteriorated under Catherine II. As part of the anti-French coalition with Britain and Austria, Russia led fighting in the Mediterranean and the Alps (Italian and Swiss campaigns of Alexander Suvorov).

Both the war itself and foreign policy in general progressed quite successfully for the Russian Empire. Pavel knew how to analyze circumstances and foresee consequences. He knew that sooner or later a figure like Napoleon would appear in France if no one stopped it. It was for this reason that the Russian Empire entered the anti-French coalition.

Despite discrimination from Soviet historians, Paul was an intelligent and competent emperor, but foreign policy distracted him from attention at his own court.

On March 11, 1801, a group of disgruntled noble conspirators burst into the sovereign's bedchamber demanding that the ruler abdicate the throne. After refusal All-Russian Emperor was killed, his reign lasted a short 5 years. The people rejoiced, not knowing what exactly this man could have prevented First Patriotic War with Napoleon Bonaparte.

Pavel Petrovich, Grand Duke, Emperor Paul I (1754-1801) was born on September 20, 1754 in the Summer Palace of Empress Elizabeth Petrovna. The only son of Grand Duke Peter Fedorovich, then Emperor Peter III, married to Grand Duchess Ekaterina Alekseevna, then Empress Catherine II. From birth he was taken away from his mother and raised under the guidance of his great-aunt Elizaveta Petrovna. In 1761, upon the accession of Father Peter III to the throne, he was declared heir to the throne and Tsarevich. From 1760 to 1773, the Grand Duke's tutor was Count N.I. Panin. In 1762, S.A. was appointed a cavalier under the Tsarevich and a teacher of mathematics. Poroshin, former aide-de-camp of Peter III. Poroshin left diaries where he not only described the Tsarevich’s daily activities, but also his character and behavior. His spiritual mentor, Hieromonk of the Trinity-Sergius Lavra Platon, later Metropolitan, played a major role in shaping the moral character and worldview of the Tsarevich. Pavel Petrovich received a comprehensive education at home.

Having ascended the throne, Catherine II in 1762 appointed her son colonel of the Cuirassier regiment named after him and admiral general, but to matters public administration I didn’t allow my son. In 1763, the Empress gave her son Stone Island. This is the first residence of the Grand Duke.

On September 29, 1773, Pavel Petrovich married Grand Duchess Natalia Alekseevna (nee Princess Wilhelmina of Hesse-Darmstadt), who died in childbirth in April 1776.

On September 26, 1776, he entered into a second marriage with Grand Duchess Maria Feodorovna (nee Princess Sophia Dorothea of Württemberg). Had 10 children: Alexandra (1777-1825), Konstantin (1779-1831), Alexandra (1783-1801), Elena (1784-1803), Maria (1786-1859), Catherine (1788-1819), Olga (1792- 1795), Anna (1795-1865), Nicholas (1796-1855), Mikhail (1798-1849).

In 1777, on the occasion of the birth of his first-born son Alexander, he received Pavlovsk as a gift from his mother, the Empress, and in 1783, after the birth of his first daughter Alexandra, he received Gatchina. In 1781-1782 Together with his wife Maria Fedorovna, he made a long trip around Europe under the name of Count of the North. Many different works of art were brought from the trip, which were included in the artistic decoration of the Pavlovsk and Gatchina palaces. In 1787 he took part in the Russian-Swedish campaign. Before leaving, he left Maria Feodorovna a number of documents, among which was a Will, as well as a draft of the future law on succession to the throne, which was approved after the coronation of Paul I.

On November 7, 1796, he ascended the throne after the death of Catherine II, and was crowned in Moscow on April 5, 1797. At the same time, a decree on succession to the throne was promulgated, which strengthened the dynasty by legitimizing the transfer of the throne from father to son, the provision on the Imperial family, the Establishment on Russian orders and the Manifesto on the three-day corvee. The new emperor released all those detained “on a secret expedition” and granted a general amnesty to all ranks who were under trial and investigation. Novikov was released from the Shlisselburg fortress, Radishchev was returned from Siberian exile, and T. Kosciuszko was released. One of the first state-political steps of the new emperor was the transfer of the remains of his father Peter III from the Alexander Nevsky Lavra to Peter and Paul Fortress with the coronation ceremony of the deceased, which caused a mixed reaction among contemporaries.

In the area domestic policy Paul I carried out serious reforms of the army and navy, which affected all aspects of the armed forces - organization, management, weapons, uniforms, supplies. The most serious and useful changes occurred in artillery and shipbuilding. Paul I inherited an almost ruined state treasury, so financial reform was very important; it was necessary to increase the ruble exchange rate and reduce the deficit. Reformed government bodies management, legal proceedings, education, civil law. To develop the domestic economy and increase its share in the domestic market, colleges were restored, later transformed into ministries, and new manufactories were built. All areas were affected by corruption and lack of executive discipline of officials. The reduction of corvee for serfs to three days and the right of peasants to file complaints against their landowners had a progressive character. However, legal proceedings were hampered by bureaucratic delays of officials. Establishing order and discipline required strict regulation, which even invaded private life. In order to maintain calm in Russia and prevent the penetration of ideas french revolution Bans were imposed on French literature and periodicals, as well as on French goods and even fashion.

In the field of cultural policy, a lot has been done to develop the theater, especially with the appointment of A.L. to the post of director of the Imperial Theaters. Naryshkina. For the Academy of Arts in 1796 they were acquired through the mediation of Prince N.B. Yusupov, copies of antiques, and under his leadership, by the end of 1798, the artists of the Academy: I. Akimov, M. Voinov, F. Gordeev, M. Kozlovsky G. Ugryumov executed a catalog of paintings, drawings and prints stored in the Hermitage and other imperial palaces . Quite intensive civil construction was going on in St. Petersburg: the buildings of the Medical-Surgical Academy and the Mint (architect A. Porto), the Maltese Chapel at the Corps of Pages, one of the last creations of D. Quarenghi, the Barracks and Manege of the Cavalry Regiment, the first work in St. Petersburg by the architect L. Ruska, as well as the Court Singing Chapel and the Public Library. The architect F. Demertsov erected two churches - Znamenskaya and St. Sergius of Radonezh, which were destroyed during the Soviet period. The year 1800 also saw the beginning of the construction of the Kazan Cathedral, which was preceded by a competition in which first place was given to the young architect A. Voronikhin. Of greatest interest is the architectural ensemble of the Mikhailovsky Castle, in front of which, at the request of Paul I, a statue of Peter the Great by K. Rastrelli was erected, and in 1801 - a monument to Suvorov on the Champ de Mars, ordered by the emperor to the sculptor M. Kozlovsky.

A number of transformations and innovations affected the sphere of education, both secular and spiritual. Being a very pious man, Paul paid great attention to church education. In 1797, the St. Petersburg and Kazan seminaries were transformed into Theological Academies, 8 new seminaries were opened in Russia, and in the dioceses, by special decree, Russian ones were opened primary schools for the preparation of psalmists. Much attention was also paid to military and naval educational institutions. One of major events in the field of education was the opening of the Protestant University of Dorpat.

In the field of foreign policy, three facts are particularly noteworthy. In 1798, Paul I supported the Order of Malta, which was defeated French troops and for this he was proclaimed first the protector (defender) of the order, and then the Chief Master of the order. The priories of the Order of Malta appeared in Russia, and its symbols were included in the Russian coat of arms. In 1799, Russia joined the anti-French coalition together with Austria, and the Russian army led by A.V. Suvorov won brilliant victories in the Italian and Swiss campaigns. Convinced of the betrayal of Austria, Paul I abruptly changes his political course and moves towards rapprochement with Napoleon Bonaparte, agreeing to a joint campaign in India with the aim of weakening England. This was one of the reasons for the death of the emperor. The museum has a large collection of museum items related to the personality of Paul I. In the state halls and living rooms of the palace there are furnishings purchased or ordered by the emperor, and also received by him as a gift. There is a huge amount of iconographic material in miniatures, graphic and painting works, in particular portraits by J. Voil, D. Levitsky, V. Borovikovsky, G. Kügelchen, S. Tonchi and others. There are also personal and memorial things of the emperor: notebooks, books, writing instruments, costumes.

Literature: Bokhanov A.N. Pavel I. M.: Veche, 2010. (Great historical figures); Brickner A.G. History of Pavel I. M.: Ast, Astrel, 2004; Valishevsky K. Son of the Great Catherine. Emperor Paul I. His life, reign and death. Reprint. M.: IKPA, 1990; Zakharov V.A. Emperor Paul I and the Order of St. John of Jerusalem. St. Petersburg: Aletheya, 2007; Zubov V.P. Pavel I. St. Petersburg: Aletheya, 2007; Emperor Paul I. Album-catalogue of the exhibition at the Manege Central Exhibition Hall (Compiled by L.V. Koval, E.N. Larina, T.A. Litvin) St. Petersburg, 2004; Kobeko D. Tsesarevich Pavel Petrovich (1754-1796). St. Petersburg: League Plus, 2001; Muruzi P. Pavel I. M.: Veche, 2005 (translation from French); Obolensky G.L. Emperor Paul I. M.: Russian word, 2001; Peskov A.M. Pavel I. M.: Young Guard, 2003; Rossomakhin A.A., Khrustalev D.G. The Challenge of Emperor Paul, or the First Myth of the 19th Century. St. Petersburg: European University, 2011; Russian Hamlet. (Compiled by A. Skorobogatov) M.: Sergei Dubov Foundation, 2004. (History of Russia and the House of Romanov in the memoirs of contemporaries of the 17th-20th centuries); Skorobogatov A.V. Tsarevich Pavel Petrovich. Political discourse and social practice. M., 2005; Shilder N.K. Emperor Paul I. M.: World of Books, 2007. (Great dynasties of Russia. Romanovs); Shumigorsky E.S. Emperor Paul I: life and reign. St. Petersburg, 1907; Eidelman N.Ya. Edge of centuries. Political struggle in Russia. Late XVIII - early XIX centuries. St. Petersburg: St. Petersburg Committee of the Union of Writers of the RSFSR, 1992; Yurkevich E.I. Military Petersburg in the era of Paul I. M.: Tsentrpoligraf, 2007.

Russian Hamlet - that’s what Pavel Petrovich Romanov’s subjects called him. His fate is tragic. From childhood, not knowing parental affection, brought up under the leadership of the crowned Elizabeth Petrovna, who saw him as her successor, he spent many years in the shadow of his mother, Empress Catherine II.

Having become a ruler at the age of 42, he was never accepted by his surroundings and died at the hands of the conspirators. His reign was short-lived - he led the country for only four years.

Birth

Paul the First, whose biography is very interesting, was born in 1754, in the Summer Palace of his crowned relative, Empress Elizabeth Petrovna, daughter of Peter I. She was his great-aunt. The parents were Peter III (the future emperor, who reigned for only a short time) and Catherine II (having overthrown her husband, she shone on the throne for 34 years).

Elizaveta Petrovna had no children, but she wanted to leave the Russian throne to an heir from the Romanov family. She chose her nephew, the son of Anna's older sister, 14-year-old Karl, who was brought to Russia and named Pyotr Fedorovich.

Separation from parents

By the time Pavel was born, Elizaveta Petrovna was disappointed in his father. She did not see in him the qualities that would help him become a worthy ruler. When Paul was born, the empress decided to raise him herself and make him her successor. Therefore, immediately after birth, the boy was surrounded by a huge staff of nannies, and the parents were actually removed from the child. Peter III was quite happy with the opportunity to see his son once a week, since he was not sure that this was his son, although he officially recognized Paul. Catherine, even if at first she had tender feelings for the child, later became more and more distant from him. This was explained by the fact that from birth she could see her son very rarely and only with the permission of the empress. In addition, he was born from an unloved husband, whose hostility gradually spread to Paul.

Upbringing

We worked seriously with the future emperor. Elizaveta Petrovna drew up special instructions, which outlined the main points of training, and appointed Nikita Ivanovich Panin, a man of extensive knowledge, as the boy’s teacher.

He prepared a program of subjects that the heir was supposed to study. It included natural sciences, history, music, dancing, God's law, geography, foreign languages, drawing, astronomy. Thanks to Panin, Pavel was surrounded by the most educated people of that time. So much attention was paid to the upbringing of the future emperor that the circle of his peers was even limited. Only children from the most noble families were allowed to communicate with the heir.

Paul the First was a capable student, although restless. The education he received was the best at that time. But the heir’s lifestyle was more like a barracks life: getting up at six in the morning and studying all day with breaks for lunch and dinner. In the evenings, completely unchildish entertainment awaited him - balls and receptions. It is not surprising that in such an environment, and deprived of parental affection, Pavel the First grew up as a nervous and insecure person.

Appearance

The future emperor was ugly. If his eldest son Alexander was considered the first handsome man, then the emperor could not be classified as a person with an attractive appearance. He had a very large convex forehead, a small snub nose, slightly bulging eyes and wide lips.

Contemporaries noted that the emperor had an extraordinary beautiful eyes. In moments of anger, Paul the First's face was distorted, making him even uglier, but in a state of peace and benevolence, his features could even be called pleasant.

Living in Mother's Shadow

When Pavel was 8 years old, his mother organized a coup. As a result, Peter III abdicated the throne and a week later died in Ropsha, where he was transported after his abdication. According to the official version, the cause of death was colic, but persistent rumors circulated among the people about the murder of the deposed emperor.

Carrying out a coup d'etat, Catherine used her son as an opportunity to rule the country until he came of age. Peter I issued a decree according to which the current ruler appointed the heir. Therefore, Catherine could only become regent for her young son. In fact, from the moment of the coup she had no intention of sharing power with anyone. And so it turned out that mother and son became rivals. Paul the First posed a considerable danger, since there were enough people at court who wanted to see him as ruler, and not Catherine. He had to be monitored and all attempts at independence had to be suppressed.

Family

In 1773, the future emperor married Princess Wilhelmina. After baptism, the first wife of Paul the First became Natalya Alekseevna.

He was madly in love and she cheated on him. Two years later, his wife died in childbirth, and Pavel was inconsolable. Catherine showed him his wife’s love correspondence with Count Razumovsky, and this news completely crippled him. But the dynasty was not to be interrupted, and in the same year Pavel was introduced to his future wife, Maria Fedorovna. She, like her first wife, came from German lands, but was distinguished by her calm and gentle character. Despite the ugly appearance of the future emperor, she loved her husband with all her heart and gave him 10 children.

The wives of Paul the First were very different in character. If the first, Natalya Alekseevna, actively tried to participate in political life and ruled her husband despotically, then Maria Fedorovna did not interfere in the affairs of government and was only concerned with her family. Her compliance and lack of ambition impressed Catherine II.

Favorites

Pavel loved his first wife immensely. He also felt tender affection for Maria Fedorovna for a long time. But over time, however, their opinions on various issues diverged more and more, which caused an inevitable cooling. His wife preferred to live in a residence in Pavlovsk, while Pavel preferred Gatchina, which he remodeled to his own taste.

Soon he was tired of his wife’s classic beauty. Favorites appeared: first Ekaterina Nelidova, and then Anna Lopukhina. Continuing to love her husband, Maria Fedorovna was forced to treat his hobbies favorably.

Children

The emperor had no children from his first marriage; his second brought him four boys and six girls.

The eldest sons of Paul the First, Alexander and Konstantin, were in a special position with Catherine II. Not trusting her daughter-in-law and her son, she did exactly the same thing as they had treated her - she took away her grandchildren and began raising them herself. Relations with his son went wrong for a long time; in politics, he held opposing views and saw him as his heir great empress I didn't want to. She planned to appoint her eldest and beloved grandson Alexander as her successor. Naturally, these intentions became known to Pavel, which greatly worsened his relationship with his eldest son. He did not trust him, and Alexander, in turn, was afraid of his father’s changeable mood.

The sons of Paul the First took after their mother. Tall, stately, with a beautiful complexion and good physical health, in appearance they were very different from their father. Only in Konstantin were the features of a parent more noticeable.

Accession to the throne

In 1797, Paul the First was crowned and received the Russian throne. The first thing he did after ascending the throne was to order the ashes of Peter III to be removed from the grave, crowned and reburied on the same day as Catherine II in a neighboring grave. After the death of his mother, he thus reunited her with her husband.

The reign of Paul the First - major reforms

On the Russian throne was, in fact, an idealist and romantic with a difficult character, whose decisions were accepted with hostility by those around him. Historians have long reconsidered their attitude to the reforms of Paul the First and consider them in many ways reasonable and useful for the state.

The way he was illegally removed from power prompted the emperor to cancel Peter I's decree on succession to the throne and issue a new one. Now power passed through the male line from father to eldest son. A woman could take the throne only if the male branch of the dynasty ended.

Pavel I paid great attention to military reform. The size of the army was reduced, and the training of army personnel was intensified. The guard was replenished by immigrants from Gatchina. The emperor fired all the undersized people who were in the army. Strict discipline and innovations caused discontent among some officers.

The reforms also affected the peasantry. The emperor issued a decree “On three-day corvee”, which caused indignation on the part of the landowners.

In foreign policy, Russia under Paul made sharp turns - it made an unexpected rapprochement with revolutionary France and entered into confrontation with England, its long-time ally.

The murder of Paul the First: a chronicle of events

By 1801, the emperor’s natural suspiciousness and suspicion had acquired monstrous proportions. He did not even trust his family, and his subjects fell into disgrace for the slightest offenses.

His close associates and long-time opponents took part in the conspiracy against Paul the First. On the night of March 11-12, 1801, he was killed in the newly built Mikhailovsky Palace. There is no exact evidence of Alexander Pavlovich’s participation in the events that took place. It is believed that he was informed of the plot, but demanded immunity for his father. Paul refused to sign his abdication and was killed during the ensuing scuffle. How exactly this happened is unknown. According to one version, death occurred from a blow to the temple with a snuffbox, while according to another, the emperor was strangled with a scarf.

Paul the First, Russian emperor and autocrat, lived a rather short life, full of tragic events, and repeated the path of his father.