>Biographies of famous people

Brief biography of Grigory Perelman

Grigory Perelman is an outstanding Soviet mathematician who was the first to prove the Poincaré conjecture. Grigory Yakovlevich Perelman was born on June 13, 1966 in Leningrad in the family of an electrical engineer from Israel and a mathematics teacher at a vocational school. IN school years Grigory additionally studied mathematics with Sergei Rushkin, associate professor of the Russian State Pedagogical University, whose students have repeatedly won awards at mathematical Olympiads. Gregory's first victory took place in 1982, when he, having flawlessly solved all the problems, received a gold medal at the International Mathematical Olympiad held in Budapest.

In addition to mathematics, the boy was interested in table tennis and music. Perelman graduated from school No. 239 with a physics and mathematics focus, but did not receive a gold medal only because of physical education, since he could not pass the GTO standards. Despite this, he was admitted to the Faculty of Mathematics and Mechanics at Leningrad State University without exams. During the years he spent at the university, he repeatedly participated in faculty and all-Union competitions and always won. His studies were easy for him and all his years were excellent, for which the future mathematician received a Lenin scholarship. Immediately after graduating from university, I entered graduate school. Having defended his PhD in 1990, he remained to work at the institute as a senior researcher.

In the early 1990s, Perelman moved to the United States, where he worked at several universities. It was during this period that he became interested in one of the most complex and unsolved problems of modern mathematics - the Poincaré Conjecture. In 1996, the scientist returned to his homeland, where he continued to work on solving a complex hypothesis. A few years later, he published three articles on the Internet in which he originally described methods for solving the Poincaré conjecture. In scientific circles, this turned into an international sensation, and the mathematician’s articles immediately made him famous. They began to invite him to best universities world for public lectures.

From 2004 to 2006, three independent groups of mathematicians from different countries began to verify the results of Perelman’s work. Almost all of them came to the same conclusion that the hypothesis was successfully solved. During the same period, Grigory decides to resign from his position at the institute and now leads a rather secluded lifestyle.

Grigory Yakovlevich Perelman was born on June 13, 1966 in Leningrad (now St. Petersburg) in the family of a mathematics teacher and an electrical engineer. From early childhood, Perelman became interested not only in mathematics, but also in music. His mother, Lyubov Leibovna, plays the violin beautifully, and it is thanks to her that the brilliant mathematician has retained his love for classical music to this day. My father taught me to play chess and gave me “Entertaining Physics,” which was popular in the last century.

The talented child studied in an ordinary Leningrad high school, located far from the city center, until the 9th grade. However, already in the 5th grade he actively attended the mathematics center, headed by S. Rukshin, associate professor of the Russian State Pedagogical University.

The first victory was won at the international school olympiad in mathematics in Hungary. The only award in his life that Perelman did not refuse is the gold medal, which he was awarded in Budapest. After 9th grade, G. Perelman studied at the 239th Leningrad Physics and Mathematics School. At the same time I went to music school. Gold medal upon completion high school was not received, since the not very athletic young man was unable to pass the GTO standards. Today there is an unprecedented competition at the lyceum - up to ten people per place.

He received his higher education at the Faculty of Mathematics and Mechanics of Leningrad State University, where he was admitted without any exams. During the entire time he had an increased scholarship to them. V. I. Lenin. He graduated from the university with honors, and Perelman entered graduate school under his leadership. A.D. Alexandrov under LOMI, and later POMI. V. A. Steklova. After defending his dissertation for a candidate's degree (1990), he remains at his own university as a senior researcher.

At the dawn of the 90s, G. Ya. Perelman worked as a researcher at several higher educational institutions in America - New York and Stony Brook. Since 1993, an internship for two years in the same place where he writes a whole series scientific works. In 1994 he speaks at the Zurich IMC Congress. He is offered a job at Stanford, Tel Aviv, etc. Unpretentious and simple in everyday life, the Russian scientist amazed his American scientific friends with his modesty, eating mostly bread and cheese and washing them down with milk.

In 1996, Perelman was awarded the European Society Prize for Young Mathematicians. The scientist does not accept it. In November 2002, Perelman blew up the minds of all mathematicians in the world. He publishes not somewhere in a reputable scientific journal, but directly on the Internet his conclusions on the Poincaré conjecture. Despite the lack of clear references and its brevity, the publication excited many. In 2003, Perelman gave lectures to US students and scientists about his work. Upon returning to St. Petersburg, the scientist stops all communication with former colleagues.

In 2005, Perelman stopped visiting his place of work, as they say, because at will, and in 2006, the Petersburger’s proof was recognized as the scientific breakthrough of the year, which happened for the first time in relation to “mental gymnastics”. Let us recall that the hypothesis about the probable forms of the Universe was put forward by a French mathematician a century ago. It was for her proof that Perelman was awarded the prestigious Fields Medal. There was a refusal from the Russian scientist. In March 2010, the Clay Mathematical Institute awarded him $1 million. Perelman also did not agree to accept them. Subsequently (2011) it was obtained by the Henri Poincaré Institute in Paris.

So, Perelman is the winner of three prizes, which he himself voluntarily refused. These include: awards of the European Mathematical Society (1996), Fields Medal (2006), Clay Mathematical Institute Millennium Prize (2010). In 2011, they decided to nominate Grigory Perelman from the St. Petersburg branch of the Mathematical Institute named after. Steklov into Russian academicians. The scientist did not give personal consent, they could not even find him, so at the moment the brilliant mathematician is not an academician.

The main work of the scientist is considered to be the Poincaré Hypothesis, but his work is not limited to this. There are three known articles, “The entropy formula for the Ricci flow and its geometric applications,” and the method of cognition itself is now called the Hamilton-Perelman theory. Previously, scientists proved the hypothesis about the soul (1994). Perelman is often credited with the authorship of the famous "Entertaining Physics". In fact, the author of the book is another person - Yakov Isidorovich Perelman (1882-1942).

The personality of G. Ya. Perelman is so unusual that a lot of jokes have already been invented about him. It is worth noting that Perelman’s character in these masterpieces folk art He is always characterized positively, and if they laugh at him, it is in a very kind way, as at a favorite fairy-tale hero. For example:

Sonya, are you aware that the mathematician Grigory Perelman did not reveal his desire to become an academician? Russian Academy. He didn't even respond to letters or calls.

- Apparently, at this time, as usual, mushrooms appeared...

In addition to funny stories, even proverbs and sayings appeared. Grigory Perelman's law: there is no offer that cannot be refused.

Today, the world-famous scientist lives in a modest St. Petersburg apartment in Kupchino with his old mother. However, at the place of registration on the street. He appears to Furshtatskaya extremely rarely, only to collect bills. He avoids journalists and communicates with few people. The scientist is still friends with his teacher and mentor, S. Rukshin, who works at Lyceum No. 239, and turns to him for advice. According to the latest data, the quiet genius Perelman is unemployed.

Grigory Perelman gained the reputation of an eccentric hermit and strange man. Some even call him the St. Petersburg “rain man.” It’s probably not a matter of some disease, rumors about which journalists love to savor. It’s just that real science, which opens up new worlds for humanity, does not tolerate fuss. It is to Perelman that the words of his colleague at the institute Yu. Burago can be attributed: “Mathematics depends on depth.” The world-famous quiet genius rightfully occupies 9th place among the hundred brilliant people of our time.

The hero of the new issue of the “Icon of the Era” column is Russian mathematician Grigory Perelman. What is known about him is that he gave up a million dollars by proving the Poincaré Conjecture, which, in turn, is known to be extremely difficult to understand. Moreover, the sequence here is exactly this - the fact of refusing money excited the respectable public much more than “some kind of abstract mathematical calculation.” Now that the hype around this decision has subsided, let’s figure out who Grigory Perelman is for mathematics and what mathematics is for him.

Grigory Perelman

Born in 1966 in Leningrad

mathematician

Life path

Soviet Union had an outstanding mathematical tradition, therefore it is impossible to talk about Perelman’s childhood without mentioning the phenomenon of Soviet mathematics schools. In them, talented children were trained under the guidance of the best mentors; such an environment served as fertile soil for future outstanding achievements. However, despite the competent organization of the learning process, there was also discrimination inherent in the Soviet system, when even having an unusual surname could cost a place in the city’s national team or admission to a university.

Henri Poincaré

Perelman grew up in an intelligent family and showed interest in mathematics from childhood. However, once he got into the mathematical circle, he did not immediately become a leader. The first failures spurred him to work harder and influenced his character - unyielding and stubborn. These qualities helped the scientist decide main task own life.

Following a gold medal at the International Mathematical Olympiad in Budapest in 1982 and a brilliant graduation (there were not enough GTO standards passed for the gold medal) followed by Mathematical and Mechanics of St. Petersburg State University, and later graduate school, where Perelman also studied exclusively with “excellent” marks. When the Soviet Union ceased to exist, the scientist was faced with reality: science was experiencing a severe crisis. An internship in the USA unexpectedly took place, where the young scientist first met Richard Hamilton. The American mathematician made serious progress in solving the famous Poincaré problem. Moreover, he even outlined a plan, following which this decision could be reached. Perelman managed to communicate with him, and Hamilton made an indelible impression on him: he was open and spared no effort in explaining.

Institute building named after. Steklova in St. Petersburg

Despite offers to stay, at the end of the internship, Perelman returned to Russia, to his home apartment in a nine-story building in St. Petersburg in Kupchino (the notorious "ghetto" in the south of the city), and began working at the Mathematical Institute. Steklova. IN free time he reflected on the Poincaré Hypothesis and the ideas that Hamilton had told him about. At this time, the American, judging by the publications, was unable to advance further in his reasoning. Soviet education gave Perelman the opportunity to look at the problem from the other side, using his own approach. Hamilton no longer responded to letters, and this became the “green light” for Perelman: he began working on solving the Hypothesis.

Every simply connected compact three-dimensional manifold without boundary is homeomorphic to a three-dimensional sphere.

The Poincaré conjecture belongs to topology, the branch of mathematics that studies the most general properties space. Like any other branch of mathematics, topology is extremely specific and precise in its formulations. Any simplifications and retellings in a “more accessible form” distort the essence and have little in common with the original. That is why, in the framework of this article, we will not talk about the well-known thought experiment with a mug, which, through continuous deformation, turns into a donut. Out of respect for the main character, we simply admit that it is difficult to explain the Poincaré Hypothesis to people far from mathematics. And for those who are ready to devote time and effort to this, we will provide several materials for independent study.

- Uspensky V.V. "From Poincaré to Perelman", part one

- Uspensky V.V. "From Poincaré to Perelman", part two

- Uspensky V.V. “From Poincaré to Perelman”, part three

The three-dimensional sphere is the object referred to in the formulation of the Poincaré Hypothesis

It took Perelman seven years to solve this problem. He did not recognize conventions and sent his works to scientific journals I did not submit it for review (a common practice among scientists). In November 2002, Perelman published the first part of his calculations on arXiv.org, followed by two more. In them, in an extremely condensed form, a problem even more general than the Poincaré Hypothesis was solved - this is the Thurston Geometrization Hypothesis, from which the first was a simple consequence. However, the scientific community received these works with caution. I was confused by the brevity of the solution and the complexity of the calculations that Perelman presented.

After the publication of the decision, Perelman again went to the United States. For several months he held seminars at various universities, talking about his work and patiently answering all questions. However, the main purpose of his trip was to meet with Hamilton. It was not possible to communicate with the American scientist a second time, but Perelman again received an invitation to stay. He received a letter from Harvard asking him to send them his resume, to which he irritably replied: “If they know my work, they don’t need my CV. If they need my CV, they don't know my work."

Fields Medal

The next few years were marred by an attempt by Chinese mathematicians to claim credit for the discovery.(their interests were supervised by Professor Yau, a brilliant mathematician, one of the creators mathematical apparatus String Theory), the unbearably long wait for verification of the work, which was carried out by three groups of scientists, and the hype in the press.

All this went against Perelman’s principles. Mathematics attracted him with its categorical honesty and unambiguousness, which is the basis of this science. However, the intrigues of his colleagues, concerned about recognition and money, shook the scientist’s faith in the mathematical community, and he decided not to study mathematics anymore.

And although Perelman’s contribution was ultimately appreciated, and Yau’s claims were ignored, the mathematician did not return to science. No Fields Medal (analogue Nobel Prize for mathematicians), nor the Millennium Prize (million dollars) he didn't accept. Perelman was extremely skeptical about the hype in the press and minimized contacts with former colleagues. To this day he lives in the same apartment in Kupchino.

Timeline

Born in Leningrad.

As part of a team of schoolchildren, he participated in the International Mathematical Olympiad in Budapest.

Perelman was invited to spend a semester each at New York University and Stony Brook University.

Returned to the institute. Steklova.

november

2002 -

July 2003

Perelman posted three scientific articles on the website arXiv.org, which in an extremely condensed form contained a solution to one of the special cases of William Thurston’s Geometrization Hypothesis, leading to a proof of the Poincaré Hypothesis.

Perelman gave a series of lectures in the United States on his works.

Perelman's results were verified by three independent groups of mathematicians. All three groups concluded that Poincaré's Problem had been successfully solved, but Chinese mathematicians Zhu Xiping and Cao Huaidong, along with their teacher Yau Shintang, attempted plagiarism, claiming that they had found a "complete proof".

Exactly 15 years ago, a St. Petersburg scientist proved the Poincaré conjecture.

November 11, 2002 on one of the major portals scientific publications An article from St. Petersburg appeared on the Internet mathematician Grigory Perelman, in which he gave proof of the Poincaré conjecture.

Thus, the hypothesis became the first solved problem of the millennium - this is the name for mathematical questions whose answers have not been found for many years.

Eight years later Mathematical Institute Clay awarded the scientist a prize of one million US dollars for this achievement, but Perelman refused it, saying that he did not need the money and, moreover, did not agree with the official mathematical community.

The poor mathematician's refusal of a large sum caused surprise in all layers of society. For this and for his reclusive lifestyle, Perelman is called the strangest Russian scientist. We found out how Grigory Perelman lives and what he does today.

Mathematician No. 1

Now Grigory Perelman is 51 years old. The scientist leads a secluded life: he practically never leaves home, does not give interviews, and is not officially employed anywhere. The mathematician never had close friends, but people who know Perelman claim that he was not always like this.

“I remember Grisha as a teenager,” says Perelman’s housemate, Sergey Krasnov. – Although we live on different floors, we see each other sometimes. Previously, we could talk to his mother, Lyubov Leibovna, but now I rarely see her. She and Grigory periodically go out for a walk, but are always at home. When we see each other, they quickly nod and move on. They don't communicate with anyone. And during his school years, Grisha was no different from other boys. Of course, even then he was actively interested in science and spent a lot of time reading books, but he also found time for other things. I studied music, hung out with friends, and played sports. And then he sacrificed all his interests to mathematics. Was it worth it? Don't know".

Grigory always took first place in mathematics Olympiads, but one day victory eluded him: in the eighth grade at the All-Union Olympiad, Perelman became only second. Since then, he abandoned all his hobbies and recreation, immersing himself in books, reference books and encyclopedias. He soon caught up and became the #1 young mathematician in the country.

Reclusion

Krasnov states: none of the residents of their house doubted that Perelman would become a great scientist. “When we learned that Grisha proved the Poincaré conjecture, which no other person in the world could do, we were not even surprised,” the pensioner admits. - Of course, we were very happy for him, we decided: finally Grigory will make his way into the people, make a dizzying career! Well done, he deserves it! But he chose a different path for himself.”

Perelman refused a cash prize of a million dollars, justifying his decision by disagreement with the official mathematical community, adding that he did not need the money.

After Perelman’s name thundered throughout the world, the mathematician was invited to the USA. In America, the scientist gave presentations, exchanged experience with foreign colleagues and explained his methods of solving mathematical problems. He quickly became bored with publicity. Returning to Russia, Perelman voluntarily left his post as a leading researcher at the laboratory of mathematical physics, resigned from the St. Petersburg branch of the Steklov Mathematical Institute of the Russian Academy of Sciences, and reduced his communication with colleagues to zero.

A few years later, they wanted to make Perelman a member of the Russian Academy of Sciences, but he refused. Having stopped almost all contacts with outside world, the scientist locked himself in his apartment in Kupchino, on the outskirts of St. Petersburg, where he lives with his mother.

“Grisha was tortured by attention”

Nowadays, mathematicians very rarely leave home and spend whole days solving new problems. “Grisha and his mother live on Lyubov Leibovna’s pension,” says Krasnov. “We, the residents of the house, in no way condemn Grisha - they say, the man is in the prime of his life, but he doesn’t bring money to the family, he doesn’t help his old mother. There is no such. He is a genius, and geniuses cannot be condemned. Once they even wanted to chip in with the whole house to help them financially.But they refused - they said that they had enough. Lyubov Leibovna always said that Grisha is unpretentious: he wears jackets or boots for decades, and for lunch, macaroni and cheese is enough for him. Well, it’s not necessary, it’s not necessary.”

According to neighbors, any person in Perelman’s place would become unsociable and closed: although the mathematician has not given rise to discussion for a long time, his person still cannot be ignored.

At the heart of the USSR course towards exact sciences, which prepared the ground for achievements nuclear physics, astronautics and sports chess, lay a strong mathematical tradition. Having taken shape in the 1930s, it gave the world such scientists as Andrei Kolmogorov, Alexander Gelfond, Pavel Alexandrov and many others who succeeded in traditional (algebra, number theory) and new areas of mathematics (topology, probability theory, math statistics). In terms of the scale of interests and intellectual resources, only the American and Chinese schools could compare with the Soviet one. But they were not limited to comparison: at the macro level, the queen of sciences developed in a contradictory atmosphere of friendly suspicion. Such mutual influences also played an important role in professional life Grigory Perelman, a recognized mathematical genius, who finally proved the Poincaré conjecture and thus solved one of the seven “millennium problems.”

Сurriculum vitæ. First pages

Grigory Yakovlevich Perelman was born on June 13, 1966 in Leningrad in the family of an electrical engineer and a mathematics teacher, and ten years later he had a sister - in the future, also a candidate (more precisely, PhD) in mathematical sciences. In addition to the love of classical music instilled by his mother, Grigory showed interest in exact sciences from childhood: in the fifth grade he began attending the mathematics center at the Palace of Pioneers, and after the eighth he moved to school No. 239 with in-depth study mathematics, which he graduated without a gold medal only because of a lack of points according to the GTO standards. In 1982, as part of the school team, he received a gold medal at the 23rd International Mathematical Olympiad in Budapest and was soon enrolled in the Faculty of Mathematics and Mechanics of Leningrad state university without passing exams.

At the university, Perelman received a Lenin scholarship for exemplary studies. After graduating from the university with honors, he entered graduate school at the Leningrad branch of the Steklov Mathematical Institute of the Russian Academy of Sciences. In 1990, under scientific guidance Academician Alexander Danilovich Alexandrov (the founder of the so-called Alexandrov geometry - a branch of metric geometry) Perelman defended his PhD thesis on the topic “Saddle surfaces in Euclidean spaces”. Then, as a senior researcher, he continued to work in the laboratory of mathematical physics at the Steklov Institute, successfully developing the theory of Alexandrov spaces.

In the early 1990s, Perelman had the opportunity to work at several respected research institutions in the United States: the State University of New York at Stony Brook, the Courant Institute of Mathematical Sciences, and the University of California at Berkeley.

A turning point for the young mathematician was a meeting with Richard Hamilton, whose area of scientific interests extended in the plane of differential geometry - a new direction widely used in general theory relativity. In his works on the topology of manifolds, the American scientist was the first to use the system differential equations called Ricci flow is a nonlinear analogue of the heat equation, which describes not the temperature distribution, but the deformation of Hausdorff space, locally equivalent to Euclidean space.

Thanks to this system of equations, Hamilton was able to outline a solution to one of the seven “millennium problems” - in fact, develop an approach to proving the Poincaré conjecture.

The favor of his foreign colleague and such a fundamental problem made a great impression on Perelman. At that time, he continued to smooth out the corners of Alexandrov’s spaces - the technical difficulties seemed insurmountable, and the scientist returned again and again to the idea of Ricci flow. According to Soviet mathematician Mikhail Gromov, by focusing on these problems, Perelman became even more ascetic, which caused concern among his loved ones.

In 1994, he received an invitation to give a lecture at the International Congress of Mathematicians in Zurich, and several scientific organizations, including Princeton and Tel Aviv universities, offered him a position on the staff. In response to Stanford University's request for a resume and references, the scientist noted, “If they know my work, they don't need my CV. If they need my CV, they don’t know my work.” Despite such an abundance of tempting offers, in 1995 he decided to return to his “native” Steklov Institute.

In 1996, the European Mathematical Society awarded Perelman his first international prize, which for some reason he refused to receive.

In addition to unpretentiousness in everyday life, a passion for music (Perelman plays the violin) and a strict adherence to scientific ethics, the scientist was already distinguished by his interest in parallel solutions complex tasks. In 1994, he proved the soul hypothesis. In differential geometry, “soul” (S) means a compact totally convex totally geodesic submanifold of the Riemannian manifold (M, g). In the simplest case, that is, in the case of the Euclidean space Rn (n reflects the dimension), the soul will be any point in this space.

Perelman proved that the soul of a complete connected Riemannian manifold with sectional curvature K ≥ 0, the sectional curvature of one of the points in which is strictly positive in all directions, is a point, and the manifold itself is diffeomorphic to Rn. Mathematicians were shocked by the rare elegance of Perelman’s proof: the calculations took only two pages, while the “pre-Perelman” attempts at a solution were presented in long articles and remained unfinished.

Proof of the Poincaré hypothesis, or the blessed merger of the kitchen with the operating room

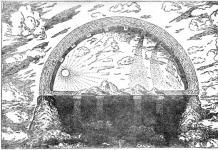

At the turn of the 19th and 20th centuries, the brilliant French mathematician Henri Poincaré enthusiastically laid the foundation of topology - the science of the properties of spaces that remain unchanged under continuous deformations. In 1900, the scientist proposed that a three-dimensional manifold, all of whose homology groups are like those of a sphere, is homeomorphic to a sphere (topologically equivalent to it). In the general case, for manifolds of any dimension, the conjecture sounds something like this: every simply connected closed n-dimensional manifold is homeomorphic to an n-dimensional sphere. Here it is necessary to at least a little decipher the terms with which Poincare used so freely.

A two-dimensional manifold is a plane: for example, the surface of a sphere or a torus (“donut”). A three-dimensional manifold is more difficult to imagine: one of its models is a dodecahedron, the opposite faces of which are “glued” to each other in a special way - identified. It was precisely for the case of a three-dimensional manifold that the Poincaré conjecture remained a tough nut to crack for a whole century. As for homeomorphism, any closed surfaces without holes are homeomorphic, that is, they can be continuously and uniquely transformed (mapped) into each other and deformed into a sphere, but with a torus, for example, this will not happen without breaking the surface, so it is not homeomorphic to the sphere , but is homeomorphic... to a mug - the same one from the kitchen cabinet. Homology is a concept that allows the construction of specific algebraic objects (groups, rings) for the study of topological spaces; it is believed that general algebraic structures are simpler than topological ones. Here are the simplest examples of homology: a closed line on a surface is homologous to zero if it serves as the boundary of some portion of this surface; Any closed line on a sphere is homologous to zero, but on a torus such a line may not be homologous to zero.

Groups—various sets that satisfy special conditions—turned out to be extremely useful for describing topological invariants—characteristics of space that do not change when it is deformed. In particular, homology groups and fundamental groups are in great demand. The homology group is put in correspondence with a topological space for the algebraic study of its properties. The fundamental group is a set of mappings of a segment into space (loops) fixed (starting and ending) at a marked point, measuring the number of “holes” in this space (“holes” arise due to the inability to continuously deform the segment into a point). Such a group is one of the topological invariants: homeomorphic spaces have the same fundamental group.

IN original version the Poincaré conjecture for three-dimensional manifolds remained “decidable”: it made it possible to weaken the condition on the fundamental group to the condition on the homology group. However, Poincaré soon eliminated this assumption by demonstrating an example of a non-standard three-dimensional homological sphere with a finite fundamental group - the “Poincaré sphere”. Such an object could be obtained, for example, by gluing each face of the dodecahedron with the opposite one, rotated by an angle π/5 clockwise. The uniqueness of the Poincaré sphere lies in the fact that it is homologous to the three-dimensional sphere, but at the same time differs from it in Euclidean space.

In its final formulation, the Poincaré conjecture sounded as follows: every simply connected compact three-dimensional manifold without boundary is homeomorphic to a three-dimensional sphere. The proof of this hypothesis promised new possibilities for modeling multidimensional spaces. In particular, the data obtained using the WMAP space probe made it possible to consider the dodecahedral Poincaré space as a possible mathematical model shapes of the Universe.

And so, in 2002–2003 (by that time the thematic correspondence between Perelman and Hamilton had already faded away), a user with the nickname Grisha Perelman, with an interval of several months, posted three articles on the arXiv.org preprint server (1, 2, 3) containing solution of a problem even more general than the Poincaré conjecture - the Thurston geometrization conjecture. And the very first publication became an international scientific sensation, although due to the author’s antipathy towards bureaucracy, not a single article made it onto the pages of peer-reviewed journals. Perelman’s calculations were so laconic and at the same time complex that mistrust simply could not help but creep into the general delight, so from 2004 to 2006, three groups of scientists from the USA and China carried out verification of Perelman’s work.

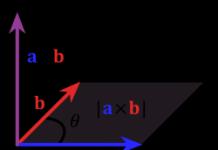

To deform the Riemannian metric on a simply connected three-dimensional manifold to a smooth metric on the target manifold, Perelman introduced new method studying the Ricci flow, which was quite rightly called the Hamilton-Perelman theory. The highlight of the method was that when approaching a singularity that arises when the metric is deformed, stop the flow applied to the manifold and cut out the “neck” (an open region diffeomorphic to the direct product) or throw out a small connected component, “sealing” the two resulting “holes” with balls . As this surgical operation is repeated, everything is discarded, each piece being diffeomorphic to a spherical spatial form, and the resulting manifold being a sphere.

As a result, Perelman managed not only to prove the Poincaré conjecture, but also to completely classify compact three-dimensional manifolds. This probably would never have happened if there had been a long list of distinctive features Perelman was not characterized by unwavering perseverance. Former mathematics teacher, candidate of physical and mathematical sciences Sergei Rushkin recalled: “Grisha began to work very hard in the ninth grade, and he turned out to have a very valuable quality for mathematics: the ability to concentrate for a very long time without much success within a task.

Still, a person needs psychological support, psychological success is needed in order to do something further. In fact, the Poincaré conjecture means almost nine years without knowing whether the problem will be solved or not. You see, even partial results were impossible there. The theorem has not been proven in full - sometimes you can even publish a twenty-page article on what actually happened. And then it’s either pan or gone.”

Eternity in your pocket

In 2003, Grigory Perelman accepted an invitation to give a series of public lectures and reports about his work in the United States. But neither students nor colleagues understood him. For several months, the mathematician patiently explained, including in personal conversations, his methods and ideas. During the “American tour,” Perelman also counted on a fruitful conversation with Hamilton, but it never took place. Returning to Russia, the scientist continued to answer questions from mathematicians via email.

In 2005, tired of the atmosphere of publicity, intrigue and endless explanations associated with the protracted verification of his calculations, Perelman resigned from the institute and actually cut off professional ties.

In 2006, all three groups of experts recognized the proof of the Poincaré conjecture as valid, to which Chinese mathematicians led by Yau Shintong, whose name appears in the name of an entire class of manifolds (Calabi-Yau spaces), responded with an attempt to challenge Perelman’s priority. True, the toolkit chosen for this turned out to be unsuccessful: it looked a lot like plagiarism. The original paper by Yau's students, Cao Huaidong, and Zhu Xiping, which filled the entire June issue of The Asian Journal of Mathematics, was annotated as the definitive proof of the Poincaré conjecture using Hamilton–Perelman theory. If you believe journalistic investigations, then even before the publication of this article, openly supervised by Yau, the latter demanded that 31 mathematicians from the journal’s editorial board as soon as possible comment on it, but for some reason did not provide the article itself.

Yau Shintun not only knew Hamilton very well, but also collaborated with him, and Perelman’s statement about successful solution The task was a surprise for both scientists: after many years of working on it, they expected, despite the temporary hitch, to reach the finish line first. Yau subsequently emphasized that Perelman's preprints were sloppy and unclear due to the lack of detailed calculations (the author provided them as needed in response to requests from independent experts), and this prevented him and everyone else from fully understanding the proof.

The attempt to belittle Perelman's merits - and Yau even kindly calculated them in percentage terms - failed, and soon Chinese scientists corrected the title and abstract of their article. Now it was to be taken not as evidence of the “crown achievement” of Chinese mathematicians, but as an “independent and detailed exposition” of the proof of the Poincaré conjecture produced by Hamilton and Perelman - without encroaching on anyone's priority. Perelman commented on Yau’s actions as follows: “I can’t say that I’m outraged, others do even worse...” Indeed, the Chinese mathematical genius can be understood: Yau later explained the zealous support of his students’ article by the desire to present the final proof in a digestible, understandable form for everyone. to consolidate in history the merits of our compatriots in solving this task of the millennium - but in fact they cannot be denied...

Meanwhile, in August 2006, Perelman was awarded the Fields Medal "for his contributions to geometry and his revolutionary ideas in the study of the geometric and analytical structure of the Ricci flow." But, like ten years ago, Perelman refused the award, and at the same time announced his reluctance to continue to remain in the status of a professional scientist. In December of the same year, Science magazine for the first time recognized Perelman’s mathematical work as “Breakthrough of the Year.” At the same time, the media burst out with a series of articles covering this achievement, although with an emphasis on the conflict that accompanied it. To defend his position, Yau turned to lawyers and threatened to sue the journalists who had “discredited his name,” but he never carried out the threat.

In 2007, Perelman took ninth place in the ranking of “One Hundred Living Geniuses” published in The Daily Telegraph. And three years later, the Clay Mathematical Institute awarded the Millennium Prize for solving the millennium problem - for the first time in history. At first, Perelman ignored the one million dollar prize, and then officially rejected it: “To put it very briefly, the main reason is disagreement with the organized mathematical community. I don't like their decisions, I think they are unfair. I believe that the contribution of the American mathematician Hamilton to solving this problem is no less than mine.”

Inflationary expansion in the representation of the Poincaré–Perelman manifold

In 2011, the Clay Institute decided to use the Millennium Prize, which Perelman refused, to pay young, promising mathematicians for whom a special temporary position was created at the Henri Poincaré Institute in Paris. At the same time, Richard Hamilton was awarded the Shao Prize in mathematics for creating a program for solving the Poincaré conjecture. The million-dollar bonus that year had to be divided equally between Hamilton and the second mathematical laureate, Demetrios Christodoulou.

Perelman retained his good attitude towards Hamilton, despite the failed dialogue and the obvious dissatisfaction of his senior colleague with the ending of this scientific history. And this says a lot about a person. According to rumors, Grigory Yakovlevich continues to live in St. Petersburg, periodically visiting Sweden, where he collaborates with a local company engaged in scientific development. Well, six problems of the millennium are still waiting for their genius.