“This is a vile, greedy, low intriguer, he needs dirt and needs money. For money he would sell his soul, and he would be right, for he would exchange a dung heap for gold” - this is how Honore Mirabeau spoke about Talleyrand , as you know, he himself was far from moral perfection. Actually, such an assessment accompanied the prince all his life. Only in his old age did he learn something like the gratitude of his descendants, which, however, was of little interest to him.

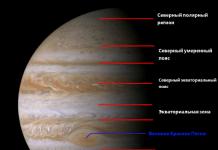

Associated with the name of Prince Charles Maurice Talleyrand-Périgord (1753-1838) an entire era. And not even alone. Royalty, Revolution, Napoleon's Empire, Restoration, July Revolution... And always, except, perhaps, from the very beginning, Talleyrand managed to be in the lead roles. Often he walked on the edge of an abyss, quite consciously exposing his head to blow, but he won, and not Napoleon, Louis, Barras and Danton. They came and went, having done their job, but Talleyrand remained. Because he always knew how to see the winner and, under the mask of greatness and inviolability, guessed the vanquished.

This is how he remained in the eyes of his descendants: unsurpassed master diplomacy, intrigue and bribes. A proud, arrogant, mocking aristocrat, gracefully hiding his limp; a cynic to the core and the “father of lies,” who never misses his advantage; a symbol of deceit, betrayal and unscrupulousness.

Charles Maurice Talleyrand came from an old aristocratic family, whose representatives served the Carolingians in the 10th century. An injury suffered in childhood did not allow him to do military career, which could improve the financial affairs of an impoverished aristocrat. His parents, who had little interest in him, directed their son along the spiritual path. How Talleyrand hated this damned cassock, which got underfoot and interfered with social entertainment! Even the example of Cardinal Richelieu could not motivate the young abbot to voluntarily reconcile with his position. Striving for a public career, Talleyrand, unlike many nobles, understood perfectly well that the age of Richelieu was over and it was too late to take an example from this great figure in history. The only thing that could console the prince was the staff of Bishop Ottensky, which brought him, in addition to its antique value, some income.

The purple cassock did not particularly interfere with the bishop's amusement. However, behind the secular leapfrog and cards, for which the prince was a great hunter, he sensitively guessed the coming changes. A storm was brewing, and it cannot be said that this upset Talleyrand. Bishop Ottensky, with all his indifference to the ideas of freedom, considered some changes necessary political system and saw perfectly well the dilapidation of the old monarchy.

The convening of the Estates General spurred the ambition of Talleyrand, who decided not to miss the chance and join the power. Bishop Ottensky became a delegate from the second estate. He quickly realized that the Bourbons were ruining themselves with indecision and stupid actions. Therefore, adhering to moderate positions, he very soon abandoned his orientation towards the king, preferring the government of the Feyants and Girondins. Not being a good speaker, Prince Talleyrand nevertheless managed to attract the attention of the now Constituent Assembly by proposing to transfer church lands to the state. The gratitude of the deputies knew no bounds. The entire dissolute life of the bishop faded into the background when he, as a faithful follower of the poor prophets, called on the church to voluntarily, without ransom, give up its “unnecessary” property. This act was all the more heroic in the eyes of citizens because everyone knew: the diocese was the only source of income for Deputy Talleyrand. The people rejoiced, and the nobles and clergy openly called the prince an apostate for his “selflessness.”

Having forced people to talk about himself, the prince still chose not to occupy the first roles in this not very stable society. He could not, and did not strive to become a people's leader, preferring more profitable and less dangerous work in various committees. Talleyrand had a presentiment that this revolution would not end well, and with cold mockery he watched the fuss of the “people's leaders”, who in the near future were to personally familiarize themselves with the invention of the revolution - the guillotine.

After August 10, 1792, much changed in the life of the revolutionary prince. The revolution has moved a little further than he would like. The sense of self-preservation took precedence over the prospects of easy income. Talleyrand realized that a bloodbath would soon begin. I had to get out of here. And he, on Danton’s instructions, wrote a lengthy note in which he outlined the principle of the need to destroy the monarchy in France, after which he preferred to quickly find himself on a diplomatic mission in London. How timely! Two and a half months later, his name was added to the lists of emigrants, having discovered two of his letters from Mirabeau, exposing his connection with the monarchy.

Naturally, Talleyrand did not go to make excuses. He remained in England. The situation was very difficult. There is no money, the British are not interested in him, the white emigration sincerely hated the defrocked bishop, who, in the name of personal gain, threw off his mantle and betrayed the interests of the king. If given the opportunity, they would destroy it. The cold and arrogant Prince Talleyrand did not attach much importance to the yapping of this pack of dogs behind his back. True, the emigrant fuss still managed to annoy him - the prince was expelled from England, he was forced to leave for America.

In Philadelphia, where he settled, the boredom of provincial life awaited him, accustomed to social entertainment. American society was obsessed with money - Talleyrand quickly noticed this. Well, if there are no secular salons, you can start a business. Since childhood, Talleyrand dreamed of becoming minister of finance. Now he had the opportunity to test his abilities. Let's say right away: he had little success here. But he began to like the developments in France more and more.

The bloody terror of the Jacobins was over. The new Thermidorian government was much more loyal. And Talleyrand persistently begins to seek the opportunity to return to his homeland, True to his rule of “letting women go first,” he, with the help beautiful ladies, and first of all Madame de Staël, managed to get the charges against him dropped. In 1796, after five years of wandering, 43-year-old Talleyrand re-entered his native land.

Talleyrand never tired of reminding the new government of himself with petitions and requests through friends. The Directory that came to power at first did not want to hear about the scandalous prince. “Talleyrand despises people so much because he studied himself a lot,” as one of the directors, Carnot, put it. However, another member of the government, Barras, feeling the instability of his position, looked with increasing attention towards Talleyrand. A supporter of the moderates, he could become “an insider” in the intrigues that the directors weaved against each other. And in 1797 Talleyrand was appointed Minister of External Relations of the French Republic. A clever intriguer, Barras did not understand people at all. He dug his own hole, first by helping Bonaparte advance, and then by securing the appointment of Talleyrand to such a post. It is these people who will remove him from power when the time comes.

Talleyrand managed to confirm his flawed reputation as a very dexterous person. Paris is accustomed to the fact that almost all government officials take bribes. But new minister foreign relations managed to shock Paris not by the number of bribes, but by their size: 13.5 million francs in two years - this was even too much for the seasoned capital. Talleyrand took everything and for any reason. It seems that there is no country left in the world that communicated with France and did not pay her to the minister. Fortunately, greed was not Talleyrand’s only quality. It was easier the more victories Bonaparte won. But the young Bonaparte would not last long. not the “sword” that Barras was counting on, but the ruler, and one should make friends with him after the victorious general returns to Paris.

Talleyrand actively supported his project of conquering Egypt, considering it necessary for France to think about colonies. The "Egyptian Expedition", a joint brainchild of the Foreign Minister and Bonaparte, was supposed to mark the beginning of a new era for France. It is not Talleyrand's fault that it failed. While the general was fighting in the hot sands of the Sahara, Talleyrand thought more and more about the fate of the Directory. Constant discord in the government, military failures, unpopularity - all these were disadvantages that threatened to develop into a disaster. When Bonaparte comes to power - and Talleyrand had no doubt that this is exactly what will happen - he is unlikely to need these narrow-minded ministers. And Talleyrand decided to untie himself from the Directory. In the summer of 1799 he unexpectedly resigned.

The former minister was not mistaken. Six months of intrigue in favor of the general were not wasted. On Brumaire 18, 1799, Bonaparte carried out a coup d'état, and nine days later Talleyrand received the portfolio of Minister of Foreign Affairs. Fate connected these people for 14 long years, seven of which the prince honestly served Napoleon. The Emperor turned out to be that rare person for whom Talleyrand felt, if not a feeling of affection, then at least respect. "I loved Napoleon... I enjoyed his fame and its reflections that fell on those who helped him in his noble cause,” Talleyrand would say many years later, when nothing connected him with the Bonapartes. Perhaps he was absolutely here sincere.

It was a sin for Talleyrand to complain about Napoleon. The emperor provided him with huge incomes, official and unofficial (the prince actively took bribes), he made his minister a great chamberlain, a great elector, a sovereign prince and the Duke of Benevento. Talleyrand became a holder of all French orders and almost all foreign ones. Napoleon, of course, despised moral qualities the prince, but also valued him very much: “He is a man of intrigue, a man of great immorality, but of great intelligence and, of course, the most capable of all the ministers I have had.” It seems that Napoleon fully understood Talleyrand. But...

1808 Erfurt. Meeting of Russian and French sovereigns. Unexpectedly, the peace of Alexander I was interrupted by the visit of Prince Talleyrand. The astonished Russian emperor listened to the strange words of the French diplomat: “Sir, why did you come here? You must save Europe, and you will succeed in this only if you resist Napoleon.” Maybe Talleyrand has gone crazy? No, that was far from the case. Back in 1807, when it seemed that Napoleon's power had reached its apogee, the prince thought about the future. How long can the emperor's triumph last? Being too sophisticated a politician, Talleyrand once again felt that it was time to leave. And in 1807 he resigned from the post of Minister of Foreign Affairs, and in 1808 he accurately determined the future winner.

The prince, showered with Napoleon's favors, played a complex game against him. Encrypted letters informed Austria and Russia about the military and diplomatic situation of France. The astute emperor had no idea that his “most capable of all ministers” was digging his grave.

The experienced diplomat was not mistaken. Napoleon's growing appetites led him to collapse in 1814. Talleyrand managed to convince the allies to leave the throne not for the son of Napoleon, whom Alexander I initially favored, but for the old royal family - the Bourbons. Hoping for gratitude on their part, the prince did the possible and the impossible, showing miracles of diplomacy. Well, gratitude from the new rulers of France was not slow to follow. Talleyrand again became minister of foreign affairs and even head of government. Now he had to decide a daunting task. The sovereigns gathered in Vienna for a congress that was supposed to decide the fate of Europe. The Great French Revolution and Emperor Napoleon redrawn the world map too much. The winners dreamed of snatching a bigger piece of the inheritance of the defeated Bonaparte. Talleyrand represented the defeated country. It seemed that the prince could only agree. But Talleyrand would not have been considered the best diplomat in Europe, "if it were so. With the most skillful intrigues, he separated the allies, forcing them to forget about their agreement during the defeat of Napoleon. France, England and Austria united against Russia and Prussia. The Congress of Vienna laid the foundations for Europe's policy on the next 60 years, and Minister Talleyrand played a decisive role in this. It was he who, in order to maintain a strong France, put forward the idea of legitimism (legality), in which all territorial acquisitions since the revolution were recognized as invalid, and the political system. European countries should have remained at the turn of 1792. France thereby retained its “natural borders.”

Perhaps the monarchs believed that in this way the revolution would be forgotten. But Prince Talleyrand was wiser than them. Unlike the Bourbons, who took the principle of legitimism seriously in domestic policy, Talleyrand, using the example of Napoleon’s “Hundred Days,” saw that it was madness to go back. It was only Louis XVIII who believed that he had regained the rightful throne of his ancestors. The Foreign Minister knew very well that the king was sitting on the throne of Bonaparte. The wave that unfolded in 1815 " white terror"When the most popular people fell victim to the tyranny of the brutal nobility, led the Bourbons to death. Talleyrand, relying on his authority, tried to explain to the foolish monarch and especially his brother, the future king Charles X, the destructiveness of such a policy. In vain! Despite his aristocratic origins, Talleyrand was so hateful new government that she did not demand his head from the king. The minister's ultimatum demanding an end to the repression led to his resignation. The “grateful” Bourbons threw Talleyrand out of the political arena for 15 years. The prince was surprised, but not upset. He was confident, despite his 62 years, that his time would come.

Work on “Memoirs” did not leave the prince aside from political life. He closely monitored the situation in the country and looked closely at young politicians. In 1830 the July Revolution broke out. The old fox remained true to himself here too. As the guns roared, he told his secretary: “We are winning.” - “We? Who exactly, prince, wins?” - “Hush, don’t say another word; I’ll tell you tomorrow.” Louis-Philippe d'Orléans won. Talleyrand, 77, was quick to join the new government. Rather, out of interest in a complex matter, he agreed to head the most difficult embassy in London. Even if the free press poured mud on the old diplomat, recalling his past “betrayals,” Talleyrand was unattainable for her. He has already become history. His authority was so high that the prince’s mere appearance on the side of Louis Philippe was regarded as the stability of the new regime. By his mere presence, Talleyrand forced the reluctant European governments to recognize the new regime in France.

The last brilliant action that the seasoned diplomat managed to carry out was the declaration of independence of Belgium, which was very beneficial for France. It was an amazing success!

Let us not judge Talleyrand as he deserves - this is the right of a historian. Although it is difficult to blame a person for being too smart and perspicacious. Politics was for Talleyrand T"

the art of the possible,” a game of the mind, a way of existence. Yes, he really “sold everyone who bought it.” His principle was always, first of all, personal gain. True, he himself said that France was in first place for him. Who knows. .. Any person involved in politics certainly turns out to be stained with dirt. And Talleyrand was a professional. So let the psychologists decide.

“Has Prince Talleyrand really died? Curious to know why he needed this now?” - joked the sarcastic mocker. This high marks a person who knows well what he needs. He was a strange and mysterious person. He himself expressed his last will: "I I want them to continue to argue throughout the centuries about who I was, what I thought and what I wanted.” These disputes continue to this day.

Talleyrand Charles(in full Charles Maurice Talleyrand-Périgord; Talleyrand-Périgord), French political and statesman, diplomat, Minister of Foreign Affairs in 1797-1799 (under the Directory), in 1799-1807 (during the Consulate and Empire of Napoleon I), in 1814-1815 (under Louis XVIII). Head of the French delegation at the Congress of Vienna 1814-1815. In 1830-1834 ambassador to London. One of the most outstanding diplomats, a master of subtle diplomatic intrigue.

Talleyrand's early life

Charles Maurice was born into a noble family. The parents were absorbed in service at court, and the baby was sent to a wet nurse. One day she left the baby on the chest of drawers, the child fell, and Talleyrand remained lame for the rest of his life. The boy received his education at the Paris College Harcourt, theological seminary and the Sorbonne (1760-78). He was ordained, and at the age of 34 he became Bishop of Autun (1788).

Bishop-defrocked

Elected to the Estates General from the clergy (1789), Talleyrand actively worked in the constitutional committee, edited the Declaration of the Rights of Man and Citizen, and initiated a decree on the nationalization of church lands (December 1789), for which the Pope excommunicated him. After the fall of the monarchy, the revolutionary bishop left France (1792), which saved him from reprisals (papers were discovered exposing his secret connections with the royal court). Talleyrand spent two years in America, where he was engaged in financial speculation.

Talleyrand the diplomat

Talleyrand the diplomat

Everything contributed to Talleyrand's success in the diplomatic field - noble manners, brilliant education, the ability to speak beautifully, unsurpassed skill in intrigue, the ability to win people over. Having taken the post of Minister of Foreign Affairs under the Directory (1797), Talleyrand quickly created an effectively working apparatus of the department. He took millions in bribes from kings and governments, not for a fundamental change in position, but just for editorial changes to some minor article in the treaty. As a minister of the Directory, Talleyrand relied on General Bonaparte and became one of the organizers of the coup on November 9, 1799. He was a minister during the period of his ascension and greatest successes (1799-1807) and played an important role in the formation of Napoleonic power. But gradually common sense began to tell Talleyrand that France’s struggle for European dominance would not bring him dividends. And then the Napoleonic nobleman, senator, Prince Benaventsky (1806), behind the back of his emperor, comes into contact with England, becomes a secret Russian agent “Anna Ivanovna”. At the time of Napoleon's abdication (1813), Talleyrand headed the provisional government, and at the Vienna Congress of European Powers (1814-15) he represented France as a minister of Louis XVIII. Having put forward the principle of legitimism (legality), Talleyrand managed to defend not only the pre-war borders of France, despite its defeat, but also to create a secret alliance of France, Austria and England against Russia and Prussia. France was brought out of international isolation. The Congress was the pinnacle of Talleyrand's diplomatic career.

After the Hundred Days, Talleyrand retired for a long time (1815-30). The returning aristocrats abhorred the stripped hair and the bribe-taker. And he, in turn, despised the ultra-royalists for their desire to turn back the wheel of history. After the revolution of 1830, Talleyrand immediately supported the new king Louis-Philippe d'Orléans. The 76-year-old diplomat was again in demand and was sent as ambassador to London (1830-1834).

Talleyrand's personality

A deeply cynical person, Talleyrand did not bind himself to any moral prohibitions. Brilliant, charming, witty, he knew how to attract women. Talleyrand was married (by the will of Napoleon) to Catherine Grand (1802), from whom he soon separated. For the last 25 years, Talleyrand had his nephew's wife, the young Duchess Dorothea Dino, at his side. Talleyrand surrounded himself with exquisite luxury and owned the richest court in Valence. Alien to sentimentality, pragmatic, he gladly recognized himself as a major owner and acted in the interests of his own kind.

Charles Mauricede Talleyran-Périgord

In politics there are no convictions, there are circumstances.

Politician and diplomat, Bishop of Autun (defrocked), Minister of Foreign Affairs of three governments.

Talleyrand was born into a noble but poor aristocratic family. The ancestors of the future diplomat came from Adalbert of Périgord, a vassal of Hugo Capet. The father of the newborn, Charles Daniel Talleyrand, was only 20 years old. His wife Alexandrina Maria Victoria Eleonora was six years older than her husband. The couple were completely absorbed in their service at court, they were constantly traveling between Paris and Versailles, and the child was sent to a wet nurse, where, apparently, he received a leg injury, which is why he limped so much for the rest of his life that he could not could walk without a cane.

According to his memoirs, Talleyrand spent the happiest years of his childhood at the estate of his great-grandmother, Countess Rochechouart-Montemar, Colbert’s granddaughter. “She was the first woman in my family who showed love for me, and she was also the first who let me experience the happiness of falling in love. May my gratitude be given to her... Yes, I loved her very much. Her memory is still dear to me,” Talleyrand wrote when he was already sixty-five years old. - How many times in my life have I regretted her. How many times have I felt with bitterness how valuable it is for a person to have sincere love for him in his own family.”

In September 1760, Charles Maurice entered the College d'Harcourt in Paris. By the time he completed his studies, in 1768, the fourteen-year-old boy had received all the knowledge traditional for a nobleman. Many character traits have already developed: external restraint, the ability to hide one’s thoughts.

He then studied at the Seminary of Saint-Sulpice (1770-1773) and at the Sorbonne. Received a licentiate degree in theology. In 1779 Talleyrand was ordained a priest.

In 1780, Talleyrand became the General Agent of the Gallican (French) Church at court. For five years, he, together with Raymond de Boisgelon, Archbishop of Aachen, was in charge of the property and finances of the Gallican Church. In 1788 Talleyrand became Bishop of Autun.

Were approaching revolutionary events 1789 Talleyrand at all costs wanted to become a deputy from the local clergy to the Estates General. He proposed a program of reforms leading to a bourgeois monarchy:

1) legally determine the rights of each citizen;

2) recognition of any public act as legal in the kingdom only with the consent of the nation;

3) the people also have control over finances;

4) the foundations of public order - property and freedom: no one can be deprived of freedom except by law;

5) punishments should be the same for all citizens;

6) conduct an inventory of property in the kingdom and create a unified national bank.

On April 2, 1789, he was elected deputy to the Estates General from the clergy of Autun. On April 12, Easter Day, he left for Paris.

French scientist Albert Soboul noted: “Talleyrand always remained Talleyrand. For him, personal interests, his lame self, stood at the center of the universe, but he was talented. In 1789-1791 he was as if drunk from the fresh air of the revolution. He objectively, regardless of his inner motives and calculations, worked for the rising class - the big bourgeoisie, to which he was attracted by the ringing of gold and the feeling of the proximity of power.

On May 5, 1789, the Estates General began its work in Versailles. There, the young bishop energetically and for good money sold his vote to one faction or another. Mirabeau spoke about him in his hearts: “Talleyrand would have sold honor, friends and even his soul for money. And I wouldn’t go wrong if I received gold for a dung heap.”

Talleyrand was one of the few who openly advocated the inviolability of the king's personality. He sincerely believed in the inviolability of the laws of France regarding the power of the king and tried to help Louis XVI. Talleyrand demanded an audience. In a conversation with the king, he proposed a project for saving the crown for consideration by Louis XVI, where main role was assigned to a military clash between the king’s army and the rebel forces. Talleyrand in his memoirs describes two ways to save the monarchy, but then states that “the king himself had already resigned himself to his fate and did not at all want to resist the impending events.” Upon learning of the capture of the Bastille, Talleyrand was horrified. He hated the crowd and was afraid of it, realizing that it would destroy all the “sweetness of life” that he loved.

On October 11, 1789, Bishop Talleyrand demanded the confiscation of the property of the clergy on behalf of the committee established on August 28 for the purpose of considering the loan project. Talleyrand's parliamentary career unfolded brilliantly; he was entrusted with reports on the most important issues. On February 16, 1790, Talleyrand was elected chairman of the Constituent Assembly as “ardently devoted to the cause of the revolution.” Talleyrand's popularity especially increased after on June 7, 1790, from the rostrum of the Constituent Assembly, he proposed from now on to celebrate Bastille Day as a national holiday of the Federation.

Having forced people to talk about himself, the prince still chose not to occupy the first roles in this not very stable society. He could not, and did not strive to become a people's leader, preferring more profitable and less dangerous work in various committees. Talleyrand had a presentiment that this revolution would not end well.

“To make a career, you should dress in all gray, stay in the shadows and not show initiative”

In 1792, Talleyrand traveled to Great Britain twice for informal negotiations to prevent war. In May 1792, the English government confirmed its neutrality. And yet Talleyrand’s efforts were not crowned with success - in February 1793, England and France found themselves drawn into war.

“...After August 10, 1792, I asked the temporary executive to give me an assignment to London for a certain period of time. To do this, I chose a scientific question that I had some right to take up, since it was related to the proposal I had made earlier Constituent Assembly. The matter concerned the introduction of a uniform system of weights and measures throughout the kingdom. Once the correctness of this system has been verified by scientists throughout Europe, it could be accepted everywhere. Therefore, it was useful to discuss this issue jointly with England."

His true goal, according to Talleyrand himself, was to leave France, where it seemed to him useless and even dangerous to stay, but from where he wanted to leave only with a legal passport, so as not to forever close his path to return. He came to Danton to ask for a foreign passport. Danton agreed. The passport was finally issued on September 7, and a few days later Talleyrand set foot on the English coast. On December 5, 1792, by decree of the Convention, charges were brought against Talleyrand and an arrest warrant was issued against him, as an aristocrat. Talleyrand remains abroad, although he does not declare himself an emigrant.

In 1794, in accordance with Pitt's decree (Aliens Act), the French bishop had to leave England. He is heading to the USA. There he earns his living through transactions with finance and real estate, worrying about the possibility of returning to France. In September 1796, Talleyrand arrived in Paris.

“Betrayal is a matter of date. To betray in time means to foresee.”

In 1797, thanks to the connections of his friend, Madame de Staël, he became Minister of Foreign Affairs, replacing Charles Delacroix in this post. In politics, Talleyrand relies on Bonaparte, and they become close allies. After the general's return from Egypt, Talleyrand introduced him to Abbot Sieyes and convinced the Count de Barras to renounce his membership in the Directory. After the coup d'état on November 9 (18 Brumaire), Talleyrand received the post of Minister of Foreign Affairs.

During the era of the Empire, Talleyrand takes part in the kidnapping and execution of the Duke of Enghien.

In 1805, Talleyrand took part in the signing of the Treaty of Presburg, but even then he was convinced that Napoleon’s unrestrained ambitions, his dynastic foreign policy, as well as ever-increasing megalomania, involve France in continuous wars. The prince, showered with Napoleon's favors, played a complex game against him. Encrypted letters informed Austria and Russia about the military and diplomatic situation of France. The astute emperor had no idea that his “most capable of all ministers” was digging his grave. In 1807, when signing the Treaty of Tilsit, he advocated a relatively soft position towards Russia. In August of the same 1807, openly speaking out against those resumed in 1805-1806. wars with Austria, Prussia and Russia, Talleyrand left the post of Minister of Foreign Affairs.

“In England there are only two sauces and three hundred denominations. In France, on the contrary, there are only two denominations and three hundred sauces."

At the Congress of Vienna 1814-1815. represented the interests of the new French king, but at the same time gradually defended the interests of the emerging French bourgeoisie. Proposed the principle of legitimism (recognition of the historical right of dynasties to decide the basic principles government system) to justify and protect the territorial interests of France, which consisted in maintaining the borders that existed on January 1, 1792, and preventing the territorial expansion of Prussia. This principle, however, was not supported, because it contradicted the plans of Russia and Prussia.

On January 3, 1815, a secret agreement was signed - a secret alliance was formed between France, Austria (Foreign Minister Clemens Metternich) and England (Foreign Minister Robert Stewart) against Russia and Prussia. The agreement was to be kept in the strictest confidence from Alexander and from anyone else at all. This treaty increased resistance to the Saxon project, so Alexander could decide to break or retreat. Having received everything he wanted in Poland, he did not want to quarrel, much less fight, with the three great powers.

A few days before the Battle of Waterloo, on June 9, 1815, the last meeting of the Congress of Vienna took place, as well as the signing of the Final Act, which consisted of 121 articles and 17 separate annexes. It took the form of a general treaty concluded by the eight powers who signed the Treaty of Paris; everyone else was invited to join him.

The return of Napoleon from the island of Elba, the flight of the Bourbons and the restoration of the empire took Talleyrand by surprise. Having restored the empire in March 1815, Napoleon let Talleyrand know that he would take him back into service. But Talleyrand remained in Vienna. He did not believe in the strength of the new Napoleonic reign. The Congress of Vienna was closed. On June 18, 1815, the Battle of Waterloo ended Napoleon's secondary reign. Louis XVIII was restored to the throne, and Talleyrand was dismissed three months later.

But before that, he had one more matter to settle. He was needed for a new diplomatic struggle. That was the name of the “second” Parisian world, worked out on September 19, 1815, which confirmed the previous treaty of March 30, 1814, except for several minor corrections of boundaries in favor of the allies. An indemnity was imposed on France.

“Coffee should be hot as hell, black as the devil, pure as an angel and sweet as love.”

On January 12, 1817, having finally made sure that he was removed from participation in government affairs for a long time, Talleyrand decided to start a profitable sale of one valuable product and wrote a letter to Metternich. He wrote that he secretly “stole” from state archives a huge mass of documents from Napoleon's correspondence. And although England and Russia, and Prussia, would give a lot, even five hundred thousand francs, but he, Talleyrand, in the name of his old friendship with Chancellor Metternich, wants to sell these documents stolen by him only to Austria and no one else. Would you like to buy it? Talleyrand made it clear that among the documents being sold there was something compromising the Austrian emperor and, having bought the documents, the Austrian government “could either bury them in the depths of its archives, or even destroy them.” The deal was completed. Talleyrand extremely shamelessly deceived Metternich: only 73 of the 832 documents sold were originals signed by Napoleon. Although, among the uninteresting official trash, Metternich still received the documents he needed, which were unpleasant for Austria.

Talleyrand's occupation at this time was writing memoirs and endless intrigues with London.

In 1829, Talleyrand began to get closer to Duke Louis Philippe of Orleans, a candidate for the throne. On July 27, 1830, a revolution broke out. Talleyrand sent a note to the sister of Louis Philippe, Duke of Orleans, with advice not to waste a minute and to immediately take the lead in the revolution, which at that moment was overthrowing the senior line of the Bourbon dynasty.

The position of Louis Philippe at first was not easy, especially in the face of foreign powers. Relations with Russia were completely ruined; all that remained was England, where in 1830 Louis Philippe sent old Talleyrand as ambassador. Soon, in the same 1830, Talleyrand's position in London became most brilliant.

Within a few months, Talleyrand manages to restore close contact between France and England: in fact, he controls the French foreign policy it was he, and not the Parisian ministers, whom Prince Talleyrand did not always honor even with business correspondence, but, to their greatest irritation, communicated directly with King Louis Philippe.

The wits joked: “Is Talleyrand dead? I wonder why he needed this?

IN recent years Talleyrand finished his memoirs, which he bequeathed to be published only after his death. These memoirs were kept by his mistress, Dorothea Sagan, Duchess of Dino.

During his life, by his own admission, he had to take 14 contradictory oaths. Talleyrand was distinguished by his phenomenal greed, took bribes from all governments and sovereigns who needed his help (thus, according to rough estimates, in 1797-1799 alone he received 13,650 thousand francs in gold; for softening some minor articles of the Treaty of Luneville of 1801 he received from Austria 15 million francs). In his memoirs, he is often extremely reluctant to talk about this or that episode of his life, but this is precisely what makes him believe more in what he speaks about openly. And yet he wrote in his memoirs: “I want people to argue about who I was many years after my death.”

His wish came true.

Left - Charles Maurice de Talleyrand-Périgord - French Foreign Minister, right - Napoleon Bonaparte

The name of Charles Maurice de Talleyrand-Périgord is considered synonymous with bribery, unscrupulousness and duplicity. During his career, this man managed to serve as foreign minister under three regimes. He advocated revolutionary ideas, supported Napoleon, and then worked for the restoration of the Bourbons. Talleyrand could have found himself on the scaffold many times, but he always escaped unscathed, and by the end of his life he also received absolution.

Charles Maurice de Talleyrand-Périgord

- Foreign Minister under three different regimes.

The fate of the brilliant diplomat could have turned out completely differently if not for a childhood trauma. The parents wanted little Charles to master military affairs, but they had to forget about this career, because the child injured his leg, which left him lame for the rest of his life. Years later he was nicknamed "The Lame Devil".

Charles Talleyrand entered the College d'Harcourt in Paris, and then began to study at the seminary. In 1778 he graduated from the Sorbonne as a licentiate in theology. A year later, Charles Talleyrand became a priest. His clergy did not prevent him from leading an active social life. Thanks to his excellent sense of humor, intelligence and passion for love adventures, Talleyrand was accepted with pleasure in any society.

Charles Maurice de Talleyrand-Périgord - politician end XVIII-early XIX centuries

In 1788, Talleyrand was elected as a deputy to the Estates General. There the priest proposed to approve a bill according to which church property should be nationalized. The clergy in the Vatican were outraged by such actions of Talleyrand, and in 1791 he was excommunicated for his revolutionary sentiments.

After the overthrow of the monarchy, Talleyrand went to England, then to the USA. When the Directory regime was established in France, Charles Talleyrand returned to the country and, with the help of his friend Madame de Stael, he was appointed to the post of Minister of Foreign Affairs. After a while, when the politician began to understand that revolutionary sentiments were gradually fading away, he bet on Napoleon Bonaparte and helped him become the head of France.

An 1815 caricature of Talleyrand, "The Man with Six Heads." Such a different Talleyrand under such different regimes.

While in the service of Napoleon, the minister was guided solely by his own interests: he weaved intrigues, conspired, and sold state secrets. Talleyrand's bribery was legendary. A lot of money for useful information the Minister of Foreign Affairs received from the Austrian diplomat Metternich, representatives of the English crown, Russian Emperor.

Napoleon Bonaparte. Hood. Paul Delaroche.

Under no circumstances did Charles Talleyrand betray his emotions. Even Napoleon wrote about this in his diary: “Talleyrand’s face is so impenetrable that it is completely impossible to understand him. Lannes and Murat used to joke that if he was talking to you, and at that time someone from behind gave him a kick, then you wouldn’t guess it from his face.”

When the regime of Napoleon Bonaparte was overthrown, Talleyrand managed to become Minister of Foreign Affairs under the next government - under the Bourbons.

Satire on the capitulation of Paris. Talleyrand, in the form of a fox, is bribed by three officers representing the Allies.

Towards the end of his life, Charles Talleyrand retired to his Valence estate. He established relations with the Pope and received absolution. When news of his death became known, his contemporaries only grinned: “How much did they pay him for this?”

Valence Castle, which belonged to Talleyrand in the Loire Valley.

Charles-Maurice Talleyrand, the greatest diplomat and cunning and “professional traitor” of the 19th century, still evokes a very ambivalent attitude among historians. On the one hand, all the nasty things said about him by enemies and envious people are absolutely true. And they called him - not even a liar, but “the father of lies”, “a man who sold everyone who bought him”, “a genius of betrayal”. He was denounced by revolutionaries and aristocrats, he was hated and despised by Emperor Alexander I and Napoleon, and romantic writers in the 30s of the 19th century (and he lived to see them) denounced him with all the uncompromisingness inherent in romantics.

But on the other hand, over time, Talleyrand also gained fans. He truly was the wittiest man of his time. His attacks - even against the emperor - spread throughout Paris instantly, his jokes - more terrible than insults - were awaited by all of Europe. Talleyrand was in this sense a real man of the “gallant 18th century”, remembering that ridicule is stronger than a bullet, that “a secular man is afraid not of dying, but of being ridiculed because of dirt on a silk stocking.”

But if Talleyrand had only been smart and witty, he would have been just one of many magnificent scum who are fun to quote, but you don’t want to respect. Talleyrand was a great diplomat. He won the Congress of Vienna - and returned to France everything that Napoleon had lost with his last defeats. Balzac, the greatest of Talleyrand's admirers, more than once noted that it would be worth making Talleyrand, not Napoleon, the idol of the nation. Napoleon drowned Europe in blood, killed hundreds of thousands of Frenchmen, more than half of all adult men in France, in battles in the name of his glory, and ultimately lost all his conquests – both his own and the republic’s. And Talleyrand, at the Congress of Vienna, without shedding a drop of blood, through flattery, intrigue, and persuasion, achieved the impossible: France remained within its natural borders, in a political union with England and Austria, and remained one of the strongest countries in Europe. For this alone, Prince Benevetsky atoned for all his sins - for very few politicians at all times could boast of such a result with such a modest investment.

In the 21st century, Talleyrand is remembered mainly for his brilliantly unscrupulous formula, which has become fashionable: “To betray in time is not to betray, but to foresee.” But we should not forget that its author lived in a time when, for loyalty to people, views, regimes, a person was deprived not of some goodies or positions, but of freedom and life. French Revolution taught those who wanted to survive it to take principles lightly, and Talleyrand learned the lesson. Replacing each other, the important Louis and Napoleons, the principled Robespierres and Marats, faded into oblivion... But Talleyrand remained - always in power, always with the strong, always with money. However, besides the ability to leave a sinking ship on time, the prince had many other useful principles in life, thanks to which he was probably the richest official in the entire history of France.

True, those who have read about the childhood and youth of Prince Benevetsky are little surprised by his famous cynicism and self-interest. “For most of my life I didn’t love anyone,” Talleyrand could say about himself. “But did anyone love me?” And indeed, little Charles-Maurice, who was born on February 13, 1754 in the noble but poor Peregor family, was not needed by anyone for a long time. Having barely recovered after childbirth, the boy’s mother gave the child to the nurse, and she herself went to have fun at court. The nurse often sat him on a huge cabinet and went out on business. The fact that one day the little boy fell and seriously injured his leg was also of little concern to anyone - and Charles remained lame forever. Finally, the 4-year-old baby was taken in by his loving great-grandmother. But she soon died, and the boy was sent to college.

Already in his youth, the precociously intelligent young man quickly “figured out” the reason for his troubles: he needed money for a social life at court and a decent upbringing of his three sons. The family was poor, and the sons had to be accommodated “as it happens.” The younger ones were destined for a military career, and Charles-Maurice, to military service because of his leg he was unfit - they gave him to the church, in the hope that over time he would become an abbot or bishop.

Young Talleyrand did not like this prospect very much. He loved life, luxury and women, was a cynic, like many in his time, and considered money to be his main talent and passion - the ability to obtain and increase it. But he soon realized that if he had money - and the French church was richer than the king - the cassock would not prevent him from enjoying all the pleasures of that time. “Whoever did not live before the Revolution,” he later said, “does not know, does not know all the sweetness of life.”

True, Charles-Maurice was not at all such a desperate fighter for the rights of the church. He just knew that there would always be an influential lady at court who would put in a good word for him.

Talleyrand loved women and never forgot that the favor of influential ladies, their friendship and sympathy is also capital. Women loved him. Yes, he was not good-looking, but in his presence the most brilliant gentlemen seemed narrow-minded and boring. He attracted people with his intelligence and wit, impeccable manners, and ability to say what he really wanted to hear. The conquered ladies were ready to do anything for him, and Talleyrand always took advantage of this. He never spared money and compliments for women.

The French Revolution found Talleyrand already the Bishop of Autun. He immediately understood what many aristocrats and clergy did not realize - this was serious and for a long time. At first, Talleyrand decided to “come to an agreement” with the revolution. He suddenly became a great defender of the interests of the people. Having been elected to the Estates General, he moved from the hall of the clergy to the hall for the third estate and became friends with Mirabeau. But after the fall of the Bastille and open confrontation between the aristocrats and the bourgeoisie, this was not enough.

And Talleyrand decided on another adventure. The “Third Estate” gathered to demand that church lands be taken away from the church and returned to the state. And Charles-Maurice decided to take the lead and, on behalf of the church, offered to simply donate these lands. The idea horrified the churchmen, but it made Talleyrand popular. True to himself, the Bishop of Autun, just in case, helped the other side - the king. But Charles-Maurice did not stay long in revolutionary France: in 1792, when the smell of blood was in the air, he cunningly obtained a diplomatic passport and left for England.

In England, Talleyrand discovered that the country was overrun with emigrants, for whom he was a traitor and a revolutionary. They did not shake hands with him and openly called him a scoundrel. But what’s even worse is that Talleyrand did not see the opportunity to make money. Ready for change, he left for America - and was very disappointed. “This is a country,” he joked later. “Where there are thirty-three religions and only one dish, and even that is inedible.” And there was no question of playing on the stock exchange in the then underdeveloped States. He earned some money, but it was incomparable with France. And Charles-Maurice decided to return to his homeland.

It was 1795 - the terror had already ended, and the then master of France Barras was friends with one of Talleyrand's former mistresses - Madame de Stael. Charles-Maurice fawned over his former passion for a long time, and she asked Barras for him. Talleyrand seemed smart, useful, a subtle politician and financier - and Barras, a weak and short-sighted politician, decided that such a talented person would be useful to him. He had an empty position as Minister of Foreign Affairs - and Talleyrand got it. Having learned about this, the “cold-blooded politician of the 19th century” was beside himself with happiness and endlessly repeated: “We have a post, now we’ll make a fortune from it! A huge fortune!”

Representatives of foreign countries were the first to learn about Talleyrand’s determination to earn a position. From now on, in order for their affairs to be resolved quickly and without bureaucratic red tape, it was necessary to respect the minister’s love for “sweets.” And donate to this “sweet” as much as you can. Since this practice was not new, the European ambassadors treated it with understanding. The exception was the uncouth Americans, who did not understand what they had to pay for - and pay decently. The US representative caused a huge scandal, but this did not change the ministry's policy.

By that time, the subtle scent of the newly-minted minister had sensed that the Directory was about to come to an end. And a young and talented General Bonaparte appeared on the horizon, who was ready to appreciate Talleyrand’s support and devotion. With the benefactor Barras, however, things turned out awkwardly: the victorious Napoleon sent Talleyrand to give Barras a bribe for abdicating power. Talleyrand arrived - and realized that Barras, frightened to death, would leave without any conditions. Therefore, Napoleon modestly kept the money - and Napoleon was not stingy.

In the mid-1790s, Talleyrand met the first of two women he truly loved. Catherine Grand was not a lady of his circle. The daughter of a merchant from India, a delightfully charming “blonde” who possessed, as envious women said, “encyclopedic ignorance”, was in fact an intelligent and practical woman, although absolutely not secular. She left her husband, left India and appeared in Paris in the 80s. At first, Catherine led a carefree life, relying on wealthy patrons. But during the revolution, when the knife of the guillotine began to fall more and more often on beautiful necks, Madame Grand fled to England in time, and the sailor in love with her returned to Paris and transported the jewelry she had hidden to London. In 1795, the 33-year-old beauty returned to France - and there she captivated Talleyrand.

Catherine Gran in the late 80s. Portrait of E. Vigée Lebrun

They had been living together for six months when the Directory suspected the former emigrant of espionage. Catherine was arrested - and then Talleyrand was the second and last time I lost control of myself in life. He wrote a desperate letter to Barras, where he called Catherine “very beautiful, very lazy, the least busy of all women,” assured that she was not capable of interfering in any affairs, said that he loved her and was ready to vouch for her with everything he had . Catherine was released.

The world marveled at the connection between an educated intellectual and a “beautiful fool,” not realizing that Madame Grand was both smart and far-sighted - just somewhat vain and not at all educated. She played on the stock exchange, helped Talleyrand “milk” the ambassadors, and could say to his face what he was never supposed to say. Napoleon insisted that Talleyrand marry her, for which both spent a year luring the Pope into giving permission for marriage for the former priest.

Catherine, wife of Talleyrand

Napoleon himself was the quickest to regret this marriage: Madame Talleyrand did not mince words, and in response to his advice to be less frivolous, she promised that “she would follow the example of Citizen Bonaparte in everything.”

The Napoleonic Empire was an inexhaustible source of wealth for Talleyrand. Trying to buy his loyalty, the Emperor showered him with titles, ranks, money, and lands. Prince Benevetsky had enormous influence in Europe. He, one might say, openly traded in the German principalities captured by Napoleon, took money from all applicants, and supported those who gave the largest amount. It got to the point where giving a bribe to Talleyrand was considered simply good manners - regardless of whether there was a request for him.

Napoleon greatly appreciated the diplomatic talent of Prince Benevetsky, but was not at all deceived about his spiritual qualities. Therefore, after an almost theatrical reconciliation between Talleyrand and his old enemy Fouche, the emperor replaced the prince with the stupid but loyal Marais, who on this occasion was promoted to Duke of Bassano. The next day, Talleyrand's joke went around all Paris: “There is now a greater fool in France than Marais. This is the Duke of Bassano.”

Talleyrand was offended by Napoleon's act, and even more so by the public reprimand when the emperor, having lost control of himself, shouted: “You are dirt in silk stockings!” Talleyrand publicly responded to this hysteria with only one phrase, which was returned to Napoleon for many years: “What a pity that such great man so poorly brought up.” Quietly, he decided that the former patron was also suitable for sale.

Since 1807, Talleyrand began to sell Napoleon - first to Austria, and then to Russia. Austria paid well, but the Russian Emperor Alexander, who hated Talleyrand, was sorry for the money, and the salary of “cousin Henri” (one of Talleyrand’s secret nicknames) had to be taken from trade licenses. Along the way, he sold his support against Russia to Poland, and he asked Alexander to marry Edmond de Perigord (his nephew) to Dorothea of Courland, one of the richest brides in Europe.

Talleyrand did not even imagine that he had given HIMSELF a delightful gift: only a few years passed, and young Dorothea de Périgord fell in love with him, became his friend, lover and assistant in all matters.

By the early 1810s, Talleyrand already understood that Napoleon's military mania could only end in disaster. After the failure of the Russian campaign, he played against Napoleon almost openly, and sold the potential owners of the country - the royal Bourbon dynasty - everything that could be sold - knowledge, influence, documents. Therefore, after the overthrow of Napoleon, Talleyrand easily became “a devoted servant of His Majesty Louis XVIII.”

The undoubted masterpiece of the diplomatic talents of Prince Benevetsky was the Congress of Vienna: if Talleyrand came there as a representative defeated country, which was about to be divided by the victors, then left with inviolable French “natural borders” (the current territory of France) and a secret alliance of France, Austria and England against Prussia and Russia. Moreover, Napoleon’s conqueror Alexander was not even given the opportunity to “reward” Prussia, loyal to him, with Saxon lands. This, however, cost the Saxon king a very decent amount.

Dorothea de Périgord

His victories at the Congress of Vienna were helped by his new love. Talleyrand had long quarreled with his wife. “This woman became his cross. He stopped loving her. Madame Grand’s vanity and talkativeness increased along with the increase in the size of her waist.” But other women were simply “different” until the nephew’s wife, the young and beautiful Dorothea, discovered that her friendship and understanding with her “uncle” had grown into something more. Madame de Périgord, whom the king, at Talleyrand's request, made Duchess of Dino, was Talleyrand's main assistant in diplomatic games in Vienna, and not only her beauty helped her - the daughter of the Duke of Courland was related to all European courts, including the Russian one. For obvious reasons, Charles-Maurice and Dorothea could not get married, but this was not necessary. They were together until the end of his life. Dorothea divorced her husband only in 1824, but left him much earlier. Her youngest daughter Pauline was Talleyrand's only child, and he adored her and spoiled her greatly.

Josephine-Pauline de Talleyrand-Périgord

But, despite all Talleyrand’s merits, King Louis had to remove him from the government - too many still remembered the revolutionary Bishop of Autun. When leaving, Talleyrand took from the ministry more than 800 securities, which he offered to buy for half a million francs to the Austrian Chancellor Metternich. The papers were advertised as "personal correspondence" of Napoleon. Austria shelled out the money - and immediately regretted it: there were less than a hundred autographs of the emperor, and everything else was of no interest.

In the 20s of the 19th century, Talleyrand lived so quietly that newspapers published his obituary several times. Dorothea helped him in everything, whose love was not hampered even by the 40-year age difference. The world has already forgotten about Talleyrand. But in vain. When at the end of the 1820s the position of Charles X was precarious, it was to Prince Benevetsky that the “contender”, the future Louis Philippe, came for advice. The 76-year-old man blessed the prince for the coup and agreed to accept the post of ambassador to England from his hands. The coup was a success, but European monarchs at first did not want to recognize Louis Philippe. Until they found out that Talleyrand supported the prince. “It’s a pity, it means this is serious and for a long time,” commented Nicholas I, reluctantly signing the note of recognition of Louis-Philippe.

In England, the old diplomat concluded a number of agreements (and also managed to make money on them). In 1834 he resigned, and in 1838 he died quietly in the arms of Dorothea, leaving her everything he had. The 84-year-old man outlived all his enemies, and during his lifetime he became a living legend, no longer called “venal,” but “great.” However, no one forgot about his greed and cunning. On the day of his funeral, there was a joke going around Paris: “You know, Talleyrand died. I wonder why he needed it?”