“The life and death of one person means nothing,” Yamamoto responded to Isoroku in response to warnings about impending assassination attempts on him. There were several years left before the war; a stream of threats against Vice Admiral Yamamoto came not from distant America, but from Japanese nationalists, who had great weight in decision-making and demanded new conquests.

Last photo of Admiral Yamamoto

Yamamoto Isoroku, the son of an impoverished samurai, was born on April 4, 1884 at the Academy navy In Japan, he was the seventh best performer in his class. After enlisting in the navy, Yamamoto took part in the Russo-Japanese War. During the Battle of Tsushima, the future admiral had two fingers torn off by an explosion.

In 1914, Yamamoto received the rank of lieutenant and entered the Naval Staff College in Tokyo. Two years later, he goes to study in the USA, where he studies economics at Harvard University. While in America, he developed a keen interest in military aviation.

After returning to Japan, Yamamoto Isoroku becomes second-in-command of the new Kasumigaura Air Corps (1923–25), but is soon sent to Washington. There he received the post of naval attaché at the Japanese Embassy (1925–27). In 1930, Yamamoto, with the rank of rear admiral, took part in the London Conference on Naval Disarmament.

The militarism of Japanese society at that time was steadily increasing. Yamamoto was one of the few officers to publicly voice his disapproval foreign policy Japan. He condemned the invasion of Manchuria in 1931 and the subsequent war with China. In December 1937, Yamamoto apologized to the US ambassador after the Japanese army attacked the American warship Panei, anchored near Nanjing. The official position was that the soldiers did not notice the American flag fluttering over the gunboat, but in essence this was another reckless step by the Japanese towards the disaster that World War II became for them.

Yamamoto was also against signing the Tripartite Pact of 1940, because he feared that an alliance with Nazi Germany could lead to war with the United States. He realized that the American economy was many times superior to the Japanese. Japan was not prepared for a long armed conflict that would deplete its already scarce internal resources. America, on the contrary, could increase its military power over time.

The admiral's fears came true. In the early months of 1941, Yamamoto was tasked with planning an attack on the United States. Being completely devoted to the emperor, like the entire Japanese military leadership of that time, he developed a plan for a swift attack, for which he paid the price a year and a half later. Even then, the admiral understood: the Japanese fleet could wage an offensive for six months, but would lose if the war dragged on.

Yamamoto shortly before the Russo-Japanese War, 1905

Yamamoto shortly before the Russo-Japanese War, 1905

Yamamoto authored the plan for the attack on Pearl Harbor, which started the war between Japan and the United States. The main advantage of the attacking side was surprise. On the morning of December 7, 414 aircraft took off from six Japanese aircraft carriers towards Hawaii. They attacked American airfields on the island of Oahu and ships that were at that time in Pearl Harbor. As a result of the operation, the Japanese sank 4 American battleships and 2 destroyers, destroyed 188 aircraft, inflicted heavy damage on four more battleships, and killed more than two thousand American soldiers. The US Pacific Fleet was temporarily neutralized, which allowed Japan to quickly capture most of the South East Asia.

Yamamoto then organized an invasion of the Solomon Islands and New Guinea. He also carried out raids on British colonies such as Ceylon. In the summer of 1942, Yamamoto decided to try to capture the US military base on Midway Island. He believed that armed forces Japan will be able to repeat the success of Pearl Harbor. However, these plans were not destined to come true: American intelligence cracked the code of Japanese radio transmissions and informed Admiral Chester Nimitz about the impending attack. As a result, Japan suffered a crushing defeat: the fleet lost 4 aircraft carriers with 248 aircraft, one cruiser and 2,500 people killed. In August 1942, American troops landed on Guadalcanal. The Japanese attempts to recapture the island were unsuccessful; the defeat in the naval battle on November 12–14 made this clear.

By the beginning of 1943, the Japanese fleet was significantly exhausted by the battles, and morale was rapidly declining. To encourage the soldiers, Admiral Yamamoto decided to conduct a personal inspection of Japanese military units located on the islands of Shortland and Bougainville in the southern part Pacific Ocean.

The American command wanted revenge on Admiral Yamamoto for the attack on Pearl Harbor, which forced the United States to enter the Second World War. world war ahead of schedule. Yamamoto's Pacific Inspection was a good chance for this. On April 14, 1943, as part of Operation Magic, American intelligence intercepted and deciphered a radiogram detailing his travel plan.

Yamamoto planned to depart from Rabaul at 6:00 and land on Bougainville Island at 8:00. At 8:40 he arrived by ship at Shortland, then at 9:45 on the same ship he returned to Balala at 10:30. From there at 11:00 he took off on a Mitsubishi G4M "Betty" bomber and arrived at Buin (Kahili) airfield at 11:10. At 14:00 he flew back from Buin and arrived in Rabaul at 15:40.

The secret plan for the American Operation Revenge included an attack on Yamamoto's bomber. To carry it out, 18 Lockheed P-38G Lightning fighters from the 339th Fighter Squadron of the 13th US Air Force were allocated. They had to fly 700 kilometers over the sea, reaching their target from the nearest American base. This is the longest interception mission of World War II carried out by coastal aircraft.

The fateful day has arrived. At 6:00 a.m. on April 18, two Japanese G4M Betty bombers took off from Vunakanau Airfield near Rabaul and flew a short distance to Lakunai Airfield to pick up passengers, which included Admiral Yamamoto and his staff. At 6:10 a.m., as planned, they took off, accompanied by six A6M Zero fighters from the 204th Aviation Group. The formation set off towards Bougainville strictly on schedule.

Meanwhile, American P-38G Lightnings took off from Cucum Airport on Guadalcanal. To overcome such a long journey, additional fuel tanks were installed on them. They spotted a Japanese formation in the south of Empress Augusta Bay on Bougainville. The P-38Gs split up to take care of the escort Zeros while the attack group attacked the mission's main target - two bombers, one of which contained Yamamoto.

At a distance of about one and a half kilometers, P-38G fighters were spotted by a Japanese formation. Yamamoto's bomber made a defensive maneuver, diving to a low altitude. It was followed by a second G4M. The Betty, carrying Admiral Yamamoto, was hit around 8:00 a.m. and crashed into the jungle near the village of Aku in southern Bougainville. The attack was carried out by two P-38G fighters, flown by Captain Thomas Lanphier and Lieutenant Rex Barber. Subsequent studies attributed the fatal shot to Barber. The second G4M bomber was attacked from behind by three fighters and crashed into the sea off Moyla Point.

Painting "The Death of Japanese Admiral Isoroku Yamamoto" by Sergeant Vaughn A. Bass

Painting "The Death of Japanese Admiral Isoroku Yamamoto" by Sergeant Vaughn A. Bass

The nearest Japanese post was at Aku. From there, Lieutenant Hamasuna saw smoke from the crash. At first he thought it was an American airplane that had crashed. Later, in order to identify the body of the deceased admiral, a patrol of the Japanese fleet was sent to the crash site. Yamamoto's body was taken to the former Australian outpost of Buin, and an autopsy was performed on April 20. Most published reports indicate that he died in his seat, having been shot twice in the back. However, there was another medical report, according to which Yamamoto had no visible wounds other than a cut above his eye. This gave rise to a lot of speculation that the admiral could have survived the crash, but died only a few hours later. The reason, according to this version, could be damage internal organs or shock.

Yamamoto plane crash site, April 1943.

Yamamoto plane crash site, April 1943.

After the autopsy, Yamamoto's body was cremated along with his uniform and buried on Buina. Some of his ashes were sent to Japan. He was first transported aboard the G4M1 "Betty" to Truk Island, where he was loaded onto the battleship Musashi, which departed for Tokyo on May 3, 1943. By this time, the news of the death of Yamamoto Isoroku was officially communicated to the Japanese press in the softened wording "died in action" on board the plane." On June 5, an honorary state funeral for the admiral took place in Tokyo. He was posthumously awarded the rank of Admiral of the Fleet and awarded the Order of the Chrysanthemum, first class. Yamamoto's remains were buried in the Tama Cemetery, a small part of which was given to his wife and rests in their family shrine in the city of Nagaoka.

Yamamoto's ashes are lowered from the battleship Musashi, May 23, 1943.

Yamamoto's ashes are lowered from the battleship Musashi, May 23, 1943.

Throughout the war, the United States did not report news of the attack on Yamamoto's plane, so as not to thereby reveal the fact that Japanese codes had been broken. At first, the murder of Yamamoto was attributed to the pilot Thomas Lanphier. Landing first, he immediately claimed that he had single-handedly shot down Yamamoto's plane. Without waiting for a post-mission briefing or interviewing other pilots, the victory was credited to him. The US Air Force has never officially denied this.

State funeral for Yamamoto, June 5, 1943

State funeral for Yamamoto, June 5, 1943

During the post-war investigation, it was revealed that Rex Barber, in his P-38G "Miss Virginia", was the only pilot to shoot down Yamamoto's G4M "Betty". This was the result of a lengthy controversy that spawned several review boards of the United States Air Force and the "Yamamoto Mission Association" dedicated to studying the Revenge mission. This version has a number of compelling evidence, including the testimony of the only surviving Zero pilot and an examination of the bomber wreckage. Lanphier himself claimed in a letter written to General Condon that Yamamoto's downed bomber fell into the sea.

Lieutenant Rex Barber

Lieutenant Rex Barber

The crash site is located in the jungle near Moyla Point, a few kilometers from the Panguna-Buin road, near the village of Aku. Today, the wreckage is strictly protected from theft and taking away for souvenirs. Since the 1960s Japanese delegations visited the crash site and installed a plaque on the admiral's seat. In the 1970s The fuselage door, part of the wing, Yamamoto's seat and one of the plane's control wheels were moved from the crash site to a memorial museum.

Yamamoto's grave

Yamamoto's grave

On April 18, 1943, during an inspection trip to the island of Bougainville, a plane with the Commander-in-Chief of the United Fleet, Isoroku Yamamoto, on board was shot down by American fighters. All crew members and passengers, including the legendary admiral, died...

Yamamoto Isoroku

April 4, 1884 - April 18, 1943

Yamamoto was born in Nagaoka on April 4, 1884.

He received his education at the Naval Academy (1904), Naval Staff College (1915) and Harvard University (1916).

Fun fact: upon entering the Naval Academy, Isoroku, when writing his application for admission, stated that his goal upon receiving an officer rank was “to respond to the visit of Commodore Perry.”

As is known, in February 1854, an American squadron under the command of Commodore Perry entered the Japanese harbor of Edo with a fleet of nine warships, where Perry demanded that Japan sign a trade cooperation agreement with the United States, threatening, in case of refusal, to return with even more powerful fleet and offer much more severe conditions...

Yamamoto graduated from the Naval Academy in 1904, and almost immediately after graduation he found himself in the center Russo-Japanese War, taking part in the famous Battle of Tsushima, where the Russian 2nd Pacific Squadron was completely destroyed and partly scattered. In this battle, a young Japanese officer lost two fingers of his left hand and was seriously wounded in the leg.

At the end of the First World War, Yamamoto was sent to the USA to Harvard University to study English language(from April 1919 to May 1921). While living in Boston, he became a top-notch poker player. This exciting card game, requiring the knowledge of a psychologist, was quite consistent with his temperament. In addition to maps and language, the Japanese officer was also interested in the problem of uninterrupted supply of fuel to the fleet, realizing that the coming conflict would inevitably be associated with the capabilities of the economies of the powers participating in it.

Upon his return to his homeland, Yamamoto soon became known as an expert in the construction and use of naval aviation, which was to play a decisive role in the next war. In June 1923 - March 1924 he traveled around Europe and the USA.

He taught at the Naval Academy, and in 1925 he was commander of a training division of naval aviation.

From 12/1/1925 to 11/15/1927 naval attaché in Washington. During his two years in this position, Yamamoto thoroughly studied the US Navy. His verdict to them was quite categorical: “This is not a navy, this is a golf and bridge club,” but he never had any illusions about the economic power of America.

From 20.8.1928 commander light cruiser"Isuzu."

12/10/1928 - aircraft carrier "Akagi".

In September of the same year, Isoroku Yamamoto was transferred to the General Headquarters of Naval Aviation. In October 1933, the admiral was appointed commander of the 1st aircraft carrier fleet.

From 10/3/1933, commander of the 1st aircraft carrier formation, he led the creation of a well-trained naval aviation in Japan. He achieved the adoption of a new program for the construction of aircraft for naval aviation (by 1940 their number reached 4,768).

In October 1933, the admiral was appointed commander of the 1st aircraft carrier fleet. Two years later, he received the rank of vice admiral and at the same time became deputy secretary of the navy and commander-in-chief of the 1st Fleet.

One of the initiators of the war with the United States, however, insisted that the war should end within two to three years, since, in his opinion, Japan would not be able to withstand a longer conflict. “In the first 6-12 months of the war I will demonstrate an unbroken chain of victories. But if the confrontation lasts 2-3 years, I have no confidence in the final victory,” Yamamoto said. It was from this that Yamamoto proceeded when planning the destruction by an unexpected strike of the main forces of the American fleet at the base in Pearl Harbor. In 1941-43, starting with the bombing of Pearl Harbor (12/7/1941), he personally supervised the actions of the Japanese Navy (flagship - battleship"Yamato")

At Pearl Harbor, the United States lost 6 battleships, a cruiser, 2 tankers, 13 ships were damaged, and approx. 300 aircraft, approx. lost. 1500 people Japanese losses amounted to 28 aircraft.

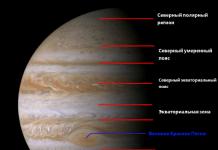

The victory at Pearl Harbor was followed by successes of the combined fleet in operations in the East Indies in January-March 1942 and in the Indian Ocean in April 1942. In June of the same year, Yamamoto led the operation to capture Midway Atoll, the purpose of which was to force a pitched battle on the Americans. Japan entered it with forces unprecedented in military maritime history. Yamamoto's fleet consisted of eight aircraft carriers, ten battleships, twenty-one cruisers, nine destroyers and fifteen large submarines. On the decks of the carrier force there were 352 famous Zero fighters and 277 bombers.

The Americans had only three aircraft carriers (one of which had been badly damaged just the day before), eight cruisers and fourteen destroyers. The balance of forces was one to three in favor of Japan, but the result, due to an almost incredible combination of circumstances, was the death of the flower of Japanese naval aviation and the hasty retreat of the Japanese fleet. This battle predetermined the impending defeat of Japan, which now, with the irreparable losses it suffered, became a matter of time. Yet Yamamoto continued to lead naval operations in the Pacific and remained the most dangerous naval commander for the United States.

When American codebreakers reported the admiral's planned inspection trip to the Japanese-defended island of Bougainville, the American command gave the order to destroy the Japanese admiral's plane using fighter aircraft.

What follows is an excerpt from the diary of Vice Admiral Ugaki Matome, Chief of Staff of the United Fleet, who was with the admiral at the time of his death.

“At 6.00 Admiral Yamamoto left Rabaul airfield on the lead aircraft, the Betty bomber. On the second plane with me were: Rear Admiral Kitamura of the quartermaster service, Captain 2nd Rank Imanaka, flag signalman, Captain 2nd Rank Muroi from the aviation department of the headquarters and our meteorologist Lieutenant Unno.

I could see our escort fighters shaking their wings. 3 fighters were flying to our left, 3 remained above and slightly behind, and 3 more stayed to the right. In total, we were accompanied by 9 fighters. Our bombers were flying very close, almost touching their wings. My plane remained to the left and slightly behind the lead one. We were flying at about 5,000 feet.

We reached the western shore of Bougainville, flying at 2200 feet above the jungle. One of the pilots handed me a note: “Estimated time of arrival at Ballala 7.45.” I involuntarily looked at my watch and noted that the time was 7:30 sharp. There were 15 minutes left before landing.

Without warning, the engines roared and the bomber dove down toward the jungle, trailing the lead plane. We leveled off at less than 200 feet. Nobody knew what happened. We anxiously scanned the sky in search of enemy fighters, which dive, attacking us. The senior pilot answered our questions: “It looks like we made a mistake. We shouldn't have dived." He was, of course, right. Our pilots should not have left their original altitude.

Our fighters spotted a group of at least 24 enemy fighters approaching from the south. They dived towards the bombers to warn them of the enemy's approach. However, at this time the bomber pilots noticed the enemy and rushed down without orders.

Already when we came out of the dive and again flew horizontally over the very jungle, our escort fighters rushed at the enemy planes. These were large Lockheed Lightning fighters. The numerically superior enemy broke through the Zero and attacked our bombers. My plane turned sharply 90 degrees. I saw the crew chief lean forward and grab the pilot's shoulder, warning him of approaching enemy fighters.

Our plane took off from the lead bomber. For several moments I lost sight of Yamamoto's bomber and finally saw it far to the right. I saw with horror that he was slowly flying just above the trees, heading south. A bright orange flame quickly engulfs its wings and fuselage. About 4 miles away, the bomber released a thick tail of thick black smoke, descending lower and lower.

The next day, a reconnaissance plane discovered the wreckage of the lead bomber in which Admiral Yamamoto met his death. Army headquarters immediately dispatched a rescue team, which found the wreckage on April 19. They picked up the bodies and headed back.

Army rescuers found Admiral Yamamoto's body in the pilot's seat, thrown from the plane. In his right hand he held his sword tightly. His body was not decomposed at all. Even in death great naval commander has not lost its greatness. For us, Yamamoto Isoroku was truly a god.

The death of Yamamoto, who was extremely popular in the Navy, had a largely negative impact on the general level of morale of the Japanese army.

On 27 May 1943 he was posthumously awarded the Knight's Cross with Oak Branches and Swords - the only foreigner to receive this German award.

Another man's story

Warrant Officer Kenji Yanagiya

Kenji Yanagiya was not the worst pilot of the Zero, but his entire life was marked by the stain of the only surviving pilot from the escort of Admiral Yamamoto's plane.

Yanagiya was born in March 1919. In January 1940, he volunteered to join the Navy; in March 1942, he completed training as a fighter pilot at Oita Air Base, after which he was assigned to the 6th Air Group.

In October 1942, Yanagia was transferred to the 204th Air Group, which was based in Rabaul. He scored his first victories on January 5, 1943, shooting down a Lightning and a Flying Fortress over Bougainville. In fact, the Americans lost two Lightnings in that air battle. Interestingly, the pilot identified the Lightning as a twin-engine Grumman XF5F-1 Skyrocket fighter. Undoubtedly, the Japanese was seriously interested in the enemy's new aircraft technology: the experimental Skyrocket was never in service with the US Air Force or Navy and did not take part in battles.

On April 18, Yanagiya and five other pilots were assigned to escort two Betty bombers, one of which was carrying an inspection visit to the theater of operations by the commander of the Combined Fleet, Admiral Isoroku Yamamoto. Sixteen Lightnings from Guadalcanal intercepted the Japanese off the southwest coast of Bougainville. The bomber carrying Admiral Yamamoto was shot down by 1st Lt. Rex Barber. Barber's attack was so swift that the Zeros did not have time to do anything. The second Betty was damaged by fire from Barber's wingman.

In the ensuing air battle, Yanagiya shot down one Lightning, but this did not change or solve anything...

After the death of Yamamoto, the Zero pilots of the escort wanted only one thing - death in battle. Over the next three months, they got their wish. Everyone except Yanagiya.

On June 8, 1943, Yanagia was seriously wounded in an air battle over Guadalcanal. He had to amputate right hand, after which the war ended for him. The pilot had eight American aircraft shot down.

In April 1988, Yanagia had the opportunity to shake hands with Rex Barber. The event took place at the Admiral Nimitz Museum in Fredericksburg, Texas. It is unlikely that Yanagiya himself experienced great satisfaction from the handshake...

Recent years Yanagiya lived in Tokyo.

In April 1943, American Lockheed P-38 Lightning fighters of the 339th Attack Squadron, operating at the maximum distance from the island of Guadalcanal, shot down a Japanese Mitsubishi Betty bomber over Kahili Atoll. Everyone on board was killed, including one very important passenger: Admiral Isoroku Yamamoto, Commander-in-Chief of the Imperial Japanese Navy and Commander-in-Chief of all Japanese military forces in the Pacific.

Yamamoto was the architect of the attack on Pearl Harbor, as well as the strategist of Japan's lightning conquests in the early months of the Pacific War. He left behind a mystery that continues to haunt historians today: was the planning of attacks in the Pacific his own work, or did he rely heavily on strategic military plans proposed by American and British naval experts before the war?

When the Japanese struck in the Pacific, they did so without fail. Some of the information was clearly provided by agents, but most intelligence could only be obtained through extensive aerial reconnaissance. It was only after the war, when Allied experts were able to study Japanese military archives, that they learned the truth. For many months before the start of the Pacific offensive, a secret flying unit of the Imperial Japanese Navy made secret flights over American bases and collected detailed photographic information. The secret unit was called the 3rd Air Corps and consisted of three squadrons total number thirty-six Mitsubishi G3M2 Nell long-range reconnaissance bombers. In April 1941, under strict secrecy, they were assembled at Takao on the island of Formosa.

On April 18, 1941, the 3rd Air Corps carried out its first mission. It was a 1200 mile flight (including way back) to photograph the harbor, airport and barracks at Legazpi on the southeastern tip of Luzon in the Philippines. The aircraft successfully circled the target at an altitude of 28,000 feet and were not detected.

On April 23, a formation of twenty-one G3M2 aircraft flew 1,400 miles across the ocean to Peleliu Airfield in the Palau Islands east of the Philippines. From there they flew secret reconnaissance flights over Jolo Island and some sites in Mindanao. Then in June, part of the Third Air Corps moved to Tinian, from where it began flying very cautious sorties at a maximum altitude of 29,500 feet over the strategic island of Guam. Over the course of three days, planes photographed the entire island in great detail. One of the planes was probably spotted because the United States government protested that a plane, believed to be of Japanese origin, had flown over the island at a very high altitude. The Japanese, of course, denied any involvement. Nevertheless, they considered it prudent to stop secret flights over the Pacific Ocean, although they increased the number of reconnaissance missions over French Indochina just before the Japanese invasion in July 1941. After this, the 3rd Air Corps was disbanded and reorganized into a combat one. unit By this time, he had provided the command of the Japanese fleet with all the necessary photographic materials, Admiral Yamamoto could now implement his plans.

Yamamoto had two qualities that were rare among Japanese officers: firstly, he perfectly understood the militaristic mentality of Japan and, secondly, he could speak and read English.

In the early 1920s he was Japan's naval attaché in Washington, during which time he had ample opportunity to read works on naval strategy written by Western experts.

One such work was a remarkable document entitled "Sea Power in the Pacific", written by a British war correspondent and former officer intelligence officer named Hector Bywater. Part of his work was devoted to the course of the future war in the Pacific Ocean and, as subsequent events showed, the predictions turned out to be highest degree accurate. The book, first published in London in 1925, has been translated into several languages, including Japanese. It began to be recommended for reading in naval colleges of leading powers. Soon after its first publication, the work, or at least that part of it, which dealt with the course of the future war in the Pacific, was expanded and expanded, becoming a full-length book. For Bywater, the hypothetical war in the Pacific begins not with a surprise attack on Pearl Harbor, but with a major battle between the Japanese and American fleets off the Philippines.

Bywater foresaw that naval guns would become the main weapons, but Bn also predicted the use of sea-based aircraft. This was not surprising, since in the mid-1920s both the British and American navies already had prototype aircraft carriers, and a spectacular demonstration of what an airplane could do to a warship was carried out in July 1921, when the joint force American army and naval bombers sank several captured German ships, including the battleship Ost Friesland.

What was surprising was the accuracy of Bywater's descriptions of future Japanese attacks on Guam and the Philippines. Guam, he predicted, would be bombarded from the air and sea, after; whereupon Japanese troops would land on the eastern and western sides of the island, capturing it in a pincer movement. The Americans will not be able to organize effective resistance and will soon be forced to surrender. This is almost exactly what happened in December 1941.

The similarities between Bywater's description of the Japanese invasion of the Philippines and actual events are truly astonishing. He predicted that the offensive would begin with massive air attacks carried out by aircraft from aircraft carriers heading to the West - and so it was; this would be followed by a trident-shaped invasion with Japanese landings at Lingayen Gulf and Lamon Bay, Luzon and Sindangan Gulf in Mindanao.

The Luzon landings happened exactly as Bywater had predicted, with the Japanese pushing in and capturing Manila from both sides. Only the Xindangan Bay landing was not a successful one: instead of landing there, on the western side of Mindanao, the Japanese invaded the shore from Davao Gulf on the southeastern tip of the island at one of the locations explored by III Air Corps aircraft. Bywater foresaw how the Americans would eventually retake the Pacific through naval power, advancing steadily toward Japan through elaborate island-hopping tactics. He also foresaw how the Japanese, in the face of defeat, would throw all available resources into battle, including suicide pilots.

Oddly enough, he could not evaluate the roles air force in this decisive naval battle. When it did occur in 1944, the opposing sides traded blows from naval aviation units while naval ships were rarely within sight of each other.

Overall, it seems that the predictions made by Bywater and the strategy adopted by Yamamoto at the beginning of the Pacific Campaign are too similar to be a coincidence.

Bywater also predicted that torpedo bombers would become the main type of aircraft used in naval combat, and in this he was completely correct. If Yamamoto needed any proof of this theory, the British provided it. In November 1940, about a year before the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, twenty Royal Navy Swordfish biplanes carrying torpedoes and bombs struck the Italian fleet at Taranto in a night attack and brilliantly destroyed the most modern battleships. ships of Italy, as well as two heavy cruisers. The battleships and one of the cruisers were put out of action for many months, and the other cruiser never went to sea again. Yamamoto learned Taranto's lessons in preparation for the attack on Pearl Harbor. The same could be said about the lessons he gleaned from the highly publicized US naval maneuvers in Hawaii in 1932, when the Americans themselves showed that several aircraft carriers could approach Pearl Harbor undetected and launch a devastating attack at dawn.

But whether Yamamoto's grand strategy in the Pacific War was based on the writings of a little-known Englishman will forever remain the most intriguing mystery of the war.

Robert JACKSON

http://ruzikrus.ru/general-yamamoto.html#more-691

Yamamoto Isoroku

(04/04/1884-04/18/1943) - Japanese admiral. Participant in the Russian-Japanese (1904-1905) and World War II (1939-1945) wars

Isoroku Yamamoto was the commander of the combined Japanese fleet during the first stage of World War II. The skillful combination of naval and air combat, of which he was a master, allowed the Japanese to win a number of victories, and Yamamoto himself became famous as the best admiral in Japan.

Yamamoto was born in Nagaoka on April 4, 1884, into the family of an impoverished samurai turned commoner. school teacher. Isoroku's parents had the surname Takano, and Isoroku later took his adoptive father's surname. In 1904, Isoroku graduated from the Naval Academy and almost immediately after graduation took part in the famous Battle of Tsushima, where the young Japanese navy almost completely destroyed the 2nd Russian Pacific Squadron.

At the end of the First World War, Isoroku Yamamoto was sent to the United States for three years at Harvard University to study English. He then served again in Japan and served as an observer on some ships. European countries. Yamamoto was interested in everything, especially the provision of fuel to the fleet, since he understood that in a future war this issue would occupy a key place in planning operations. Yamamoto soon became an expert in naval aviation, a new type of naval formation that was to play a decisive role in naval battles in the vastness of the Pacific Ocean.

In 1925, the government sent him to the United States again, this time as a naval attaché. During his two years in this position, Yamamoto carefully studied the state of the US Navy.

Returning to his homeland in 1929, he received the rank of rear admiral and took command of the aircraft carrier Akagi.

In 1930, Yamamoto took part in the London Naval Conference, at which Japan managed to achieve an equal standard in submarines with the United States and England and a fairly favorable ratio in destroyers and cruisers. But even this state of affairs seemed unfair to the Japanese.

Yamamoto quickly moved up the ranks. In September 1930 he was transferred to the General Headquarters of Naval Aviation. In October 1933, Admiral Yamamoto was appointed commander of the 1st Carrier Fleet. And two years later he received the rank of vice admiral and at the same time became deputy minister of the navy and commander-in-chief of the 1st fleet.

Unlike most of his colleagues, Yamamoto believed that the future belonged to naval aviation. Thanks to his innovation and ability to obtain significant government funds for new military programs, the admiral created one of the most powerful and strong fleets in the world by the end of the 1930s. The core of the new Japanese fleet was aircraft carriers.

By 1939, most Japanese military and political leaders began to realize that the only obstacle to gaining dominance in East Asia was the United States. Yamamoto did everything to prepare the Japanese Navy for successful solution any combat missions. But at the same time, he tried to avoid war and even opposed the signing of the Tripartite Pact with Germany and Italy. Working in the USA, he understood perfectly well that thanks to powerful industry and unlimited resources, this country would be able to defeat little Japan. Yamamoto's anti-war statements led to the fact that a conspiracy began to mature in the army with the aim of physically eliminating the admiral, which was discovered in July 1939. When asked by Konoe, who was Prime Minister at the time, about Japan’s chances in a war with the United States, the admiral answered honestly: “In the first six to twelve months of the war, I will demonstrate an unbroken chain of victories. But if the confrontation lasts two or three years, I have no confidence in the final victory.” Konoe sent Yamamoto to sea, appointing him commander-in-chief of the Combined Fleet. It is possible that by doing this he wanted to save the life of his admiral.

Admiral Yamamoto conducted staff exercises at sea, which showed that the Japanese had a chance to achieve an advantage only by delivering a surprise attack on the Hawaiian base of Pearl Harbor, where the main forces of the US Pacific Fleet were based. The admiral began to develop a plan for a surprise attack on this base. Initially main role The operation was assigned to submarines; the use of aviation was not planned. In August 1941 the situation changed. Yamamoto proposed using aircraft carriers to attack Hawaii. The decision to start the war was made by Emperor Hirohito of Japan on December 1, 1941.

Back on November 26, 1941, a fleet of six aircraft carriers and auxiliary ships under the command of Yamamoto sailed to Hawaii on the Northern sea route, which was used extremely rarely. The aircraft carriers carried about 400 aircraft. This formation was tasked with launching a surprise attack on Pearl Harbor in order to cause as much damage as possible to the US Pacific Fleet. The naval command gave this operation the code name "Operation Z". According to intelligence data, the American fleet was at its base. However, the operational plan provided for striking American ships even if they left the harbor. According to the operation plan, the Japanese fleet was supposed to secretly approach the Hawaiian Islands and destroy American ships aircraft from aircraft carriers. Aviation had to operate in two echelons with an interval of one and a half hours. If the enemy tried to strike or the Japanese met a stronger group, a preemptive strike should have been carried out. At the end of the operation, the maneuver unit was to immediately return to Japan for repairs and replenishment of ammunition.

On the morning of December 7, Japanese aircraft carriers launched a surprise attack on the American fleet at Pearl Harbor. Most of the American aircraft located on the islands were destroyed. The Japanese also managed to sink four battleships and put as many more out of action. In addition, the Americans lost a cruiser and two tankers, and many ships were seriously damaged. The first two Japanese attacks were so successful that the admiral abandoned his original intention of striking the docks and oil storage facilities. In two hours, Yamamoto managed to inflict the heaviest defeat on the American fleet in its entire history.

However main task attack - the destruction of American aircraft carriers - was not carried out. These ships were not in Pearl Harbor, since they were on maneuvers at that time. Yet the Japanese leadership perceived Yamamoto's almost flawless attack as a triumph.

In January 1941, the commander of the United Fleet, Admiral Yamamoto, received a directive from Headquarters on the main directions of attack of the Japanese army. Imperial Army and the Navy was to capture the Philippines, Thailand, Malaya and Singapore. According to the directive fighting The combined fleet was divided into three successive stages: the occupation of the Philippines, then British Malaya and finally the Dutch East Indies. To maintain supremacy at sea, Yamamoto specially created the Southern Expeditionary Fleet, whose task was to destroy American and British ships in the combat zone, as well as support operations ground forces. The commander of this formation was Vice Admiral Dzisaburo Ozawa.

The Malayan operation was considered by the Japanese command as the most important in capturing the South Seas region. During the war, the Japanese encountered virtually no resistance from the Allies. The operation ended with the surrender of the English fortress of Singapore, after which the small East Anglian Fleet was forced to leave this base and enter the Gulf of Thailand. During the battle that followed on December 10, the Japanese Navy, having lost only three aircraft, sank the battleship "Prince of Wales" and the battleship "Repulse", which basically consisted of all naval forces British in this region.

In the Philippine direction, contrary to Yamamoto's expectations, the Japanese did not encounter ships of the American fleet. At the same time, large-scale preparations were launched for offensive operations in the central and southern parts of the Pacific Ocean, which were entrusted to Admiral Yamamoto.

For this purpose, the South Seas Task Force was assigned under the command of Vice Admiral Shigiyoshi Inoue. This group was supposed to carry out patrol duty, ensure the security of maritime communications, and also capture the Wake Islands and the Rabaul base. The group's aircraft destroyed American airfields on three islands, and then the island of Guam was occupied on December 10, Wake on December 22, and Rabaul a day later. Japanese planes launched from aircraft carriers destroyed Allied aircraft in the Solomon Islands and New Guinea.

By March 1942, as a result of military operations at sea, the losses of the US fleet amounted to 5 battleships, 2 aircraft carriers, 4 cruisers and 8 destroyers. The small English fleet in this region was almost completely destroyed. On the Japanese side, only two cruisers received minor damage. One got the impression that the danger of waging an exhausting, protracted war had passed.

The Naval General Staff and the Navy Ministry, not wanting to lose the strategic initiative, insisted on the beginning of active actions against Australia. But the army advocated conducting strategic defense, refusing to seize new territories. The naval command eventually had to agree with the army's position. A compromise was reached, which consisted of conducting active operations on communications connecting the United States and Australia, in order to prevent the concentration of American troops in Australia and a subsequent attack on Japan. To achieve this, it was planned to capture the islands of Fiji, Samoa, New Caledonia and Port Moresby.

Port Moresby, located in the southeastern part of New Guinea and a major Allied air and naval base, covered northern Australia. Yamamoto set the start of the operation to capture this base on May 10, 1942. But on May 7, Allied planes sank the Japanese aircraft carrier Seho, which forced the landing to be postponed for several days. The next day, the Americans heavily damaged the aircraft carrier Shokaku and again forced Inoue to postpone the invasion, this time indefinitely.

As a result of the two-day battle in the Coral Sea, the Americans won their first victory over Yamamoto. The commander of the Combined Fleet sent orders to Admiral Inoue to continue the operation, but they were never carried out.

The operation to capture Fiji, Samoa and New Caledonia, developed by the naval department of Headquarters, was called “FS”. But first, Yamamoto wanted to capture Midway Island and the Aleutian Islands, which caused new disagreements between the army and navy. The Operations Directorate of the General Staff suspected that the Navy was going to land troops on Hawaii. The command's plans previously considered the issue of capturing Midway, so that later, having created a base on it, they could begin to capture the Hawaiian Islands. Only after lengthy explanations and assurances that the capture of the Hawaiian Islands was not currently part of the Navy's plans was permission received to begin the operation to invade Midway.

By the beginning of 1942, the United States had gradually made up for the losses it had suffered at Pearl Harbor. Therefore, the prevailing opinion in the Japanese Navy was the need for a general battle with the American fleet, as a result of which the enemy fleet would either be destroyed or weakened so much that it could not interfere with operations.

By April 1942, large Japanese Navy forces allocated for the upcoming operation began to concentrate in the area near Hashira Island in the western part of the Inland Sea of Japan. The flagship battleship Yamato, on which the headquarters of Admiral Yamamoto was located, was also located here. The combined fleet was preparing for a decisive battle.

Admiral Yamamoto's fleet consisted of 8 aircraft carriers, 10 battleships, 21 cruisers, 9 destroyers and 15 large submarines. Carrier-based aircraft consisted of 352 Zero fighters and 277 bombers. The Japanese command decided to throw all these powerful forces into capturing the island. The Americans had only 3 aircraft carriers, 8 cruisers and 14 destroyers. The ratio was one to three in favor of Japan. The admiral hoped to force the American fleet to leave Pearl Harbor, move north to the Aleutian Islands, and then try to relieve Midway and thereby fall into the trap set by Yamamoto's main units north of the atoll. The admiral did not know that American cryptographers managed to decipher the codes of the Japanese Navy and Nimitz, the commander of the US Navy, was well aware of the plans of the Japanese command. In addition, Japanese intelligence had incorrect information about the number of American aircraft carriers that survived the Battle of the Coral Sea.

On June 4, Yamamoto's fleet approached Midway, but the Japanese were met there by American aircraft carriers. Having set a trap for the Japanese, American planes attacked enemy ships and their aircraft while they were on the decks of the ships to refuel and replenish ammunition. As a result of the battle, the Americans managed to sink four of nine Japanese aircraft carriers and put an end to Yamamoto's triumphant march across the Pacific Ocean. This was the first defeat of the Japanese fleet in 350 years of existence. The war became protracted. And although the American fleet was already significantly stronger than the Japanese, Yamamoto himself remained the most dangerous enemy in the Pacific.

Having been defeated at Midway Island, the Japanese command still did not give up the fight on Australian communications. On the island of Guadalcanal, part of the Solomon Islands chain, back in May 1942, the Japanese decided to build an airfield and place a garrison. But on August 8, 1942, even before construction was completed, 13,000 US Marines suddenly landed on the island and captured the air base. Nevertheless, the Japanese managed to retain the western part of Guadalcanal. Admiral Yamamoto, given the seriousness of the situation, decided to concentrate most of his forces for a decisive blow against the enemy. On August 17, the main forces of the Combined Fleet, led by the flagship Yamato, left the Inland Sea of Japan and headed for Guadalcanal to support the ground forces and recapture the entire island.

In the following months, fierce fighting broke out around this small piece of land. The Japanese never managed to recapture the airfield and knock out marines USA from the island.

In November 1942, two battles took place, during which both sides suffered heavy losses; in February 1943, the Japanese were forced to evacuate their troops from Guadalcanal.

After the evacuation of the troops, the current situation required the urgent transfer of Japanese troops to the southeastern part of the Pacific Ocean. But the convoy accompanying the reserve units was completely destroyed by American aircraft. The danger she posed became increasingly serious. To put an end to this, Admiral Yamamoto developed a plan codenamed Operation I. More than three hundred aircraft took part in this operation. The commander-in-chief arrived in Rabaul to personally lead the fighting.

On April 7, 1943, 188 Japanese bombers raided enemy ships off Guadalcanal. In the following days, the actions of Japanese aviation were very successful. But this was Admiral Yamamoto's last operation.

The American command had been developing a plan to eliminate the Japanese admiral for some time. And when the codebreakers transmitted a message about Yamamoto’s supposed trip to units located on the island, the command decided to act.

On April 18, 1943, the commander-in-chief left Rabaul for Buin. The plane Yamamoto was flying in was attacked by specially trained and instructed American fighter pilots, and after a short battle he was shot down. This was the only attempt on the life of an enemy commander made by the Allies during the war, indicating a real fear of his name.

Skritsky Nikolay Vladimirovich

ISOROKU YAMAMOTO Yamamoto, commanding imperial fleet, achieved significant successes in the first stage of World War II thanks to a skillful combination various types Japanese navy. Naval aviation became the main force. The future naval commander was born on April 4, 1884 in

From the book World history in sayings and quotes author Dushenko Konstantin VasilievichDeath of Admiral Yamamoto

Great value The death of Admiral Isoroku Yamamoto on April 18, 1943 had a significant impact on the course of the war in the Pacific. Two days earlier, American codebreakers had deciphered an intercepted radiogram indicating that the commander of the Combined Fleet would fly from Rabaul to Buin Island to inspect the state of the defenses. His visit was kept in the strictest confidence, and many precautions were taken. The admiral was even forced to change his white uniform to the less conspicuous khaki uniform worn by most naval officers in the area. However, the commander of the seaplane base on the Shortland Islands off the southern coast of Bougainville notified his command that Yamamoto was going to visit the area. It was his radiogram that the Americans intercepted.

On April 17, a directive arrived from Washington at Henderson airfield, ordering every effort to be made to finish off the admiral. It was determined that Yamamoto's plane would take off from Rabaul at 6.00 and land at Buina on the southern tip of Bougainville at 9.45. Admiral Yamamoto was then to cross Shortland Harbor in a submarine chaser. The distance from Henderson Airfield to Buin, including turns to avoid detection by the enemy, is 435 miles. This was too much for the Navy fighters, but not for the Army P-38 Lightning fighters with drop tanks. But it was necessary to deliver these tanks on time.

On the night of April 17/18, 4 transport aircraft arrived at Henderson airfield. They delivered 18 drop tanks of 310 gallons each. Mechanics worked all night to install these tanks on twin-engine Lightnings. The most experienced pilots from 3 Lightning squadrons based at Henderson Airfield were assembled. Their aircraft were equipped with 310-gallon drop tanks and standard 165-gallon auxiliary tanks. 14 Lightnings were supposed to cover a strike group of 4 fighters, which were tasked with shooting down 2 Betty bombers, on which Yamamoto was flying with his headquarters.

Of the 4 aircraft of the strike group, one failed immediately - its tire burst on takeoff. Another P-38 was forced to return due to problems with additional tanks. 2 other aircraft were transferred from the cover group to the strike group. At 9.35 American fighters saw their desired target.

The Lightnings dropped their drop tanks and began to gain altitude. One of the strike force's P-38s failed to jettison its 310-gallon drop tank and turned back, followed by its wingman. The strike group was again reduced to 2 fighters.

Admiral Yamamoto and his staff, flying on 2 Betty bombers, were accompanied by 6 (or according to some sources 9) Zeros. The bomber pilots, noticing the Lightnings, dropped their planes down to the very tops of the trees to avoid the attack. The Zeros dropped their drop tanks and turned towards the Americans.

The Lightnings entered the fray. 2 American fighters chose Betty as their target, while the rest fought with Zero. One P-38 shot down a Zero before diving onto Admiral Yamamoto's plane. "Betty" was quickly hit, caught fire and fell into the jungle. The second Betty was also shot down and fell into the sea. 2 staff officers and the pilot of the second bomber were the only people who managed to escape. More than 20 Japanese officers were killed. During the battle, one Lightning was shot down, and most of the others were damaged. 2 American fighters were unable to reach Henderson airfield on one engine and were forced to land on another island.

The commander of the Combined Fleet and several of the best Japanese staff officers were killed in this air battle. Yamamoto's successor was Admiral Mineichi Koga, a good officer who served as Deputy Chief of the Naval General Staff and commanded the Japanese fleet in Chinese waters at the beginning of the war. Compared to Yamamoto, he was considered conservative and unflappable. Admiral Koga once remarked in a private conversation: “Admiral Yamamoto died at the right time. I envy him for this."

The next operation in the Solomon Islands area was carried out by Allied aircraft carriers in the summer of 1943 with the participation of the American aircraft carrier Saratoga and the British aircraft carrier Victorias. In December 1942, the British withdrew Victories from the Home Fleet to replenish the battered American carrier force in the Pacific. He crossed the Atlantic, passed through the Panama Canal and arrived at Pearl Harbor in March 1943. March and April were spent training with American-built aircraft. Victories received F4F Wildcat fighters and TBF Avenger torpedo bombers. In May, she arrived in Noumea, replacing the battered Enterprise for 10 weeks. This aircraft carrier was undergoing repairs at Pearl Harbor. Victories, with an American air group on board, conducted several joint exercises with Saratoga, the only American aircraft carrier in the southwest Pacific. Both aircraft carriers achieved excellent synergy. They conducted several raids against Japanese bases without encountering serious resistance from Japanese aircraft or ships.