The creator of the most profound and influential theories of intelligence development became a Swiss scientist Jean Piaget(1896-1980). He transformed the basic concepts of other schools: behaviorism (instead of the concept of reaction, he put forward the concept of operation), Gestaltism (Gestalt gave way to the concept of structure) and Janet (adopting from him the principle of interiorization, dating back to Sechenov).

Piaget puts forward the position of the genetic method as the guiding one methodological principle psychological research.

Focusing on formation of a child's intelligence, Piaget emphasized that in scientific psychology every investigation must begin with a study of development, and that it is the formation of mental mechanisms in the child that best explains their nature and functioning in the adult. According to Piaget, not only individual sciences, but also the theory of knowledge should be built on a genetic basis. This idea became the basis for his creation genetic epistemology, those. science about the mechanisms and conditions for the formation in humans of various forms and types of knowledge, concepts, cognitive operations, etc.

It is known that representatives of different approaches had different understandings of the essence of mental development. Proponents of the idealistic, introspective approach took the self-contained mental world as their starting point; Representatives of behavioral psychology understood the development of the psyche, according to M.G. Yaroshevsky, “as filling an initially “empty” organism with skills, associations, etc. under the influence of environmental conditions." Piaget rejected both of these approaches, both genetically and functionally, i.e. in relation to consciousness, mental life of an adult.

Piaget considered the starting point of his analysis interactthe effect of the whole individual- and not the psyche or consciousness - with the surrounding world. He defined intelligence as a property of a living organism, formed in the process of material contacts with the environment.

According to Piaget, in the course of ontogenetic development, the external world begins to appear to the child in the form of objects not immediately, but as a result of active interaction with him. In the course of an increasingly complete and deep interaction between the subject and the object, as the author believed, their mutual enrichment occurs: more and more new aspects and characteristics are identified in the object, and the subject develops more and more adequate, subtle and complex ways of influencing the world in order to knowledge and achievement of consciously set goals.

In his experimental and theoretical studies of the genesis of intelligence, Piaget studied only the elementary forms of activity of a developing person. The main material for the study was various forms of child behavior in the outside world. But unlike representatives of the behaviorist movement, Piaget did not limit himself to describing actions, but tried to reconstruct on their basis those mental structures, the manifestation of which is behavior. Piaget's many years of research on the reconstruction of the psyche on the basis of behavior also led him to the conclusion that mental processes themselves, not only intellectual, but also perceptual, represent a specific activity.

Piaget's main task was to study human structuressky intelligence. He considered its structure as a natural development during the evolution of less organized organic structures. However, the psychological views of J. Piaget were formed on the basis of a general biological understanding of the development process as an interconnection assimilation And accommodation. During assimilation, the organism, as it were, imposes its own patterns of behavior on the environment; during accommodation, it rearranges them in accordance with the characteristics of the environment. In this regard, the development of intelligence was thought of as a unity of assimilation and accommodation, because through these acts the organism adapts to its environment.

Piaget’s first books were published in the 20s: “Speech and Thinking of the Child” (1923), “Judgment and Inference in the Child” (1924), “The Child’s Idea of the World” (1926).

M.G. Yaroshevsky, analyzing these initial views of Piaget, writes the following: “On the way from an infant to an adult, thought undergoes a number of qualitative transformations - stages, each of which has its own characteristics. Trying to reveal them, Piaget initially focused on children's statements. He used the method of free conversation with the child, trying to ensure that the questions asked of the little subjects were as close as possible to their spontaneous statements: what makes clouds, water, wind move? where do dreams come from? why does the boat float? etc. It was not easy to find in the multitude of children's judgments, stories, retellings, replicas unifying principle, which gives grounds to distinguish “what a child has” from the cognitive activity of an adult.

So common denominator Piaget believed peculiar egocentrism of a child. little child is the unconscious center of his own world. He is not able to take the position of another, to look at himself critically, from the outside, to understand that other people see things differently.

Therefore, he confuses the objective and the subjective, the experienced and the real. He attributes his personal motives to physical things and endows all objects with consciousness and will. This is reflected in children's speech. In the presence of others, the child thinks out loud as if he were alone. He is not interested in whether he will be understood by others. His speech, expressing his desires, dreams, “logic of feelings,” serves as a kind of companion, an accompaniment to his real behavior. But life forces the child to leave the world of dreams, to adapt to the environment... And then the child’s thought loses its originality, becomes deformed and begins to obey another, “adult” logic, drawn from the social environment, i.e. from the process of verbal communication with other human beings” [Yaroshevsky M.G.].

In the 1930s, a radical change occurred in Piaget's approach to problems of mental development. In order to describe the structure of intellectual acts, he develops a special logical-mathematical apparatus.

Piaget defined the stages of development of intelligence, their content and meaning differently. Now he believed that it was not communication with other people, but the operation (logical-mathematical structure) that determined the cognitive development of the child. In 1941, in collaboration with A. Sheminskaya, the book “Genesis of Number in a Child” was published by J. Piaget, and in the same year, together with B. Inelder, “Development of the Concept of Number in a Child.” The center of the second work is the question of how a child discovers the invariance (constancy) of certain properties of objects, how his thinking assimilates the principle of conservation of matter, weight and volume of objects. Piaget found that the principle of conservation is formed in children gradually, first they begin to understand the invariance of mass (8-10 years), then weight (10-12 years) and, finally, volume (about 12 years).

To come to the idea of conservation, the child's mind, according to Piaget, must develop logical schemes representing the level (stage) of specific operations. These specific operations, in turn, have a long history. Mental action (arising from external objective action) is not yet an operation. To become such, it must acquire very special characteristics. Operations are distinguished by reversibility and coordination into the system. For each operation there is an opposite, or inverse, operation, through which the original position is restored and equilibrium is achieved. The interconnection of operations creates stable and, at the same time, mobile integral structures. Gradually, the child’s ability to make inferences and form hypotheses increases. After the age of 11, a child’s thinking moves to a new stage - formal operations, which ends by the age of 15.

When studying intelligence, Piaget used the so-called cutting method: he presented children of different ages with the same problem and compared the results of solving it. This method made it possible to detect certain shifts in the child’s intellectual activity and to see in the previous stage the emergence of prerequisites and some elements of the subsequent stage. However, this method could not ensure the disclosure of the child’s psychological formation of a new intellectual technique, concept, knowledge.

Piaget's main idea is that a child's understanding of reality is a coherent and consistent whole, allowing him to adapt to the environment. As the child grows, he passes several stages, on each of which “equilibrium” is achieved:

1. The first turning point, at about one and a half to two years, is also the end of the “sensorimotor period”. At this age, the child is able to solve various non-verbal tasks: looking for objects that have disappeared from sight, i.e. understands that the outside world exists constantly, even when it is not perceived. The child can find the way by making a detour, uses the simplest tools to get the desired object, can foresee the consequences of external influences (for example, that the ball will roll downhill, and if you push the swing, it will sway and return to its previous position).

2. The next stage, the “pre-operational stage,” is characterized by a conceptual understanding of the world and is associated with language acquisition.

3. Around the age of seven, the child reaches the stage of “concrete operations”, for example, he understands that the number of objects does not depend on whether they are arranged in a long row or in a compact pile; Previously, he could decide that there were more objects in a long row.

4. The last stage occurs in early adolescence and is called the “formal operations” stage. At this stage, a purely symbolic idea of objects and their relationships becomes available, and the ability to mentally manipulate symbols appears.

Period 1925-1929 is important in the formation of the psychological concept of J. Piaget. At this time, J. Piaget moves from the analysis of verbal thinking to a direct study of the active side of the thinking process ( It took some time, Piaget later wrote, to understand that the roots of logical operations lie deeper than linguistic connections and that my early study of thinking was too strongly focused on the linguistic aspect (See J. Piaget. Comments on Vygotsky's critical remarks)). Research materials from 1925-1929. were published by J. Piaget in the books: “The Emergence of Intelligence in the Child” (1936), “The Construction of Reality in the Child” (1937), “The Formation of the Symbol in the Child” (1945), as well as in a number of articles. Center for research in the period 1925-1929. was centered around the analysis of the structure of intelligence in the initial, pre-symbolic sensorimotor period of its development and in the subsequent period of symbolic thinking.

In 1929, Piaget began a new cycle of research (it ended around 1939). In the course of these studies, Piaget, firstly, continuing the main line of work of 1925-1929, supplemented the analysis of children's intelligence early age research intellectual development in middle age (primarily based on the analysis of the genesis of number and the concept of quantity), secondly, he formulated the main ideas of his psychological theory of thinking (the operational concept of intelligence), and, thirdly, he built his logical concept. The results of these studies were published by Piaget in the books “Genesis of Number in a Child” (together with A. Sheminskaya, 1941), “Development of Number in a Child” (together with B. Inelder, 1941), “Psychology of Intelligence” (1946), “Logic and psychology" (1953). The works “Classes, Relations and Numbers” (1942), “Logical Treatise” (1949) and others are devoted to a special presentation of the logical theory of J. Piaget. The works of J. Piaget, completed in 1929-1939, express in the clearest form the essence of his psychological and logical concept.

According to the operational concept of intelligence, the development and functioning psychic phenomena represents, on the one hand, assimilation, or assimilation of this material by existing behavioral patterns, and on the other, the accommodation of these patterns to a specific situation. Piaget views the adaptation of the organism to the environment as a balancing of subject and object. The concepts of assimilation and accommodation play a major role in the explanation of the genesis of mental functions proposed by Piaget. Essentially, this genesis acts as a sequential change of various stages of balancing assimilation and accommodation ( See J. Piaget. La psychologic de l'intelligence. Paris, 1952, p. 13-15).

Piaget emphasizes the great difficulties of developing a theory of the development of mental functions. The main one is the extreme difficulty of separating internal factors of development4 (maturation) from its external factors (actions of the environment). Classical psychology, notes Piaget, operated on three main factors of development - heredity, physical environment and social environment, but it could neither isolate them in their “pure” form, nor establish the nature of the relationships between them.

Consideration of the fundamental dependence of external and internal factors of development, Piaget continues, leads to the conclusion that all behavior is the assimilation of the given by pre-created schemes and at the same time the accommodation of these schemes to the present situation. It follows from this that “the theory of development must necessarily turn to the concept of balance, for all behavior essentially expresses a balance between internal and external factors or, more generally, between assimilation and accommodation” ( J. Piaget. Le role de la notion d"equilibre dans l"explication en psychologie. - "Actes du quinzienie congress Internationale de psychologic. Bruxelles, 1957." Amsterdam, 1959, p. 53).

Piaget proposes to consider the balance factor as the fourth main factor of development. It does not join the three preceding factors simply additively, for none of them can, strictly speaking, be separated from the others. At the same time, balance as a fourth factor has an important advantage over others: according to Piaget, balance is a more general factor and can be analyzed relatively independently ( Ibid., pp. 53-54).

Piaget emphasizes that equilibrium can be understood in two ways - as a result and as a process of balancing. Moreover, equilibrium as a process is strictly connected by Piaget with the principle of activity. Any changes external to the body can only be compensated through activity. Because of this, the maximum value of equilibrium corresponds not to a state of rest, but to the maximum value of activity, which compensates for both actual and virtual changes ( Ibid., page 53).

The concept of balance, according to Piaget, should be used as an explanatory principle for all mental functions of the body. Intelligence, or thinking, is one of these functions, the most developed and perfect (in the sense of the possibility of mastering the external world), moreover, possessing such forms of balance to which all other mental structures gravitate.

Raising the question of the genesis of intelligence and its relationship with other mental functions, Piaget clearly formulates the principle, prepared by his early research, of the derivative of internalized mental structures from external objective actions.

From Piaget's point of view, it makes no sense to talk about a "starting point" mental development, in which intelligence first appears. But it makes sense to talk about various intellectual structures that replace one another in the process of development; one can compare these structures with each other and use the concept of “degree of intelligence”; one can argue that in the process of development behavior becomes more and more intellectual.

Intelligence cannot be defined by specifying its “boundaries,” Piaget believes. The definition of intelligence can be given only through an indication of its development towards the greatest balance of cognitive structures. From this it follows, in particular, that the method of studying intelligence can only be the genetic method, since the intellectual structure, torn out of the chain of development, taken outside of its relationship to previous and subsequent forms of balancing, cannot be correctly understood.

The genesis of intelligence is expressed in the formation of such intellectual structures, each of which can be considered as a special form of equilibrium between the organism and the environment, and intellectual development leads to the formation of more and more stable forms of equilibrium.

The analysis of the sequential development of intelligence should begin, according to Piaget, with elementary sensorimotor actions. The latter, as they become more complex and differentiated, lead to the formation of a pre-operational form of intelligence associated with representation, and then to thinking of a concrete operational type and, finally, to intelligence itself, i.e., to the ability to manipulate formal operations.

The task of psychology, according to Piaget, is to give a detailed description of this process, to show how external objective actions are gradually internalized, leading to the formation of intelligence.

The essence of intellect, according to Piaget, lies in the system of operations that form it. Higher forms balancing the organism and the environment are expressed in the formation of operational intellectual structures.

According to Piaget, an operation is an internal action of a subject, derived from an external, objective action and coordinated with other operations in such a way that together they form a certain structural whole, a system.

The system of operations is characterized by the fact that in it some operations are balanced by others, reverse in relation to the first (the reverse operation is considered to be the one that, based on the results of the first operation, restores the original position). Depending on the complexity of the operating system, the forms of reversibility that occur between operations change. The psychological criterion for the emergence of operating systems is the construction of invariants, or concepts of conservation (for example, for the appearance of operations A+A"=B and A=B-A" it is necessary to realize the conservation of B) ( See J. Piaget. La psychologie de l'intelligence, p. 53-55).

Thus, the principles of activity and the derivation of internalized mental structures from external objective actions, the idea of genesis and the operational (systemic) nature of intelligence form the initial foundations of the psychological theory of J. Piaget.

The way in which Piaget tries to reveal the essential connections of intelligence is by analyzing mental operations and their systems. How is this analysis carried out?

Psychological and logical methods of studying intelligence

When analyzing intelligence, it is necessary, Piaget believes, to combine psychological and logical research plans. This statement and its clear implementation is one of the most important features of Piaget’s theory of thinking.

Although already when writing his early works, J. Piaget was well aware of the principles of the new logic - mathematical, or logistics, he, striving for the "purity" of psychological analysis, believed that attempts at a hasty deductive presentation of experimental data easily lead to the fact that the researcher finds himself " at the mercy of preconceived ideas, facile analogies suggested by the history of science and the psychology of primitive peoples, or, what is even more dangerous, at the mercy of the prejudices of a logical system or an epistemological system" ( J. Piaget. Speech and thinking of a child, p. 64) (our discharge. - V.L. and V.S.). “Classical logic (i.e., the logic of textbooks) and the naive realism of common sense,” he wrote, “are two mortal enemies of healthy cognitive psychology...” ( Ibid.).

J. Piaget's critical attitude to the “logic of textbooks” is, to a large extent, a reaction against the logicalization of the psychology of thinking, widespread in the 19th century. Piaget himself characterizes the situation that took place during that period as follows. Classical formal logic (i.e. pre-mathematical logic) believed that it was possible to reveal the actual structures of mental processes, and classical philosophical psychology in turn believed that the laws of logic are implicit in the mental functioning of every normal individual. There was no basis for disagreement between these two disciplines at that time ( J. Piaget. Logic and psychology. Manchester University Press, 1953, p. 1).

However, in the subsequent development of experimental psychology, logical factors were excluded from it as “alien” to the subject studied in it. Attempts to preserve the unity of psychological and logical research, as they took place, for example, among supporters of the Würzburg psychological school, were not successful. The use of logic in the “causal explanation of the actual psychological facts” ( J. Piaget. Logic and psychology, p. 1) was called “logicism” in psychological research and, starting from the end of the 19th century, was considered one of the most important dangers that an experimental psychologist must avoid. “Most modern psychologists,” writes J. Piaget, “are trying to explain intelligence without any recourse to logical theory” ( Ibid., page 2).

This state of affairs was also facilitated by changes in the theoretical interpretation of logic that occurred in late XIX V. Instead of understanding logic as a part of psychology, the laws of which are derived from the empirical facts of the intellectual life of people ("psychologism" in logic), the dominant consideration has become the consideration of logic as a set of formal calculi that establishes rules for transforming one linguistic form into another, which are independent of empirical psychological material and not are related to the analysis of the thinking process. Piaget quite rightly notes that “most modern logicians no longer touch upon the question of whether the laws and structures of logic have any kind of relation to psychological structures” ( Ibid.). Since the beginning of the 20th century, a seemingly insurmountable wall has formed between the psychology of thinking and modern formal logic.

Speaking in his early works for the “purity” of psychological analysis and against introducing elements of logic into psychological research, J. Piaget undoubtedly paid tribute to the prevailing views of that period. But his position, even at that time, can in no way be considered as an acceptance of the point of view of the absolute separation of psychological and logical research. Piaget fought against the introduction of elementary, “school” logic into psychology and against the interpretation of a child’s thinking from the point of view of the logical structures of an adult’s thinking, and not against the use of logic in psychology in general. In his early works, he proceeds from the fact that the thinking of an adult is logical thinking, that is, subject to a set of skills “used by the mind in the general conduct of operations” ( J. Piaget. Speech and thinking of a child, p. 97), and Piaget turns his main attention to the analysis of the specific features of a child’s logic, which is not reducible to the logical thinking of an adult ( Ibid., pp. 370-408).

Thus, already the early works of J. Piaget were essentially characterized by the desire for the unity of psychological and logical analysis. However, the real implementation of such a unified analysis was given by Piaget only in the 30s.

The main task that J. Piaget solves in his studies of problems of logic is to resolve the question of whether there is a correspondence between logical structures and the operational structures of psychology. If this issue is resolved positively, the real development of mental operations receives a logical basis.

According to J. Piaget, three main difficulties arise when comparing axiomatic logical theories with a psychological description of the real development of intelligence: 1) the thinking of an adult is not formalized; 2) the deployment of axiomatic logic in a certain respect is opposite to the genetic order of construction of operations (for example, with an axiomatic construction, the logic of classes is derived from the logic of statements, while from a genetic point of view, propositional operations are derived from the logic of classes and relations; 3) axiomatic logic has an atomic character (it is based on atomic elements) and the method of proof used in it is necessarily linear; real operations of the intellect, on the contrary, are organized into certain integral, structural formations, and only within this framework do they act as operations of thinking ( See J. Piaget. Logic and psychology, p. 24).

The axiomatic construction of logic is not, however, the starting point of logic itself. Both historically and theoretically, it is preceded by some meaningful consideration of logical concepts - in the form of an analysis of systems of logical operations (algebra of logic). It is these operational-algebraic structures that can act, according to J. Piaget, as an intermediary link between psychological and logical structures.

Taking into account the above, Piaget believes that logic and its relationship to the psychology of thinking can be given the following interpretation ( See J. Piaget. La psychologica de l'intelligence, p. 37-43).

Modern formal logic, with all its formalized and very abstract nature, is ultimately a specific reflection of thinking that actually occurs. This means that logic can be considered as an axiomatics of thinking, and the psychology of thinking as an experimental science corresponding to logic. Axiomatics is a hypothetico-deductive science that tries to minimize appeals to experience and reproduces an object using a series of unprovable statements (axioms), from which it derives all possible consequences using predetermined, strictly fixed rules. Axiomatics can be considered as a kind of “scheme” of a real object. But precisely because of the “schematic” nature of any axiomatics, it can neither replace the corresponding experimental science, nor be considered to lie at the “basis” of the latter, since the “schematism” of axiomatics is evidence of its obvious limitations.

Logic, being an ideal model of thinking, does not feel any need to appeal to psychological facts, since the hypothetico-deductive theory does not directly analyze the facts, but only at some extreme point comes into contact with experimental data. However, since a certain connection with factual data is still inherent in any hypothetico-deductive theory, since any axiomatics is a “scheme” of some really existing object, there must be some correspondence between psychology and logic (although there is never parallelism between them). This correspondence between logic and psychology occurs to the extent that psychology analyzes the final equilibrium positions that a developed intellect reaches.

In order for the data of modern formal logic to be used for explanatory purposes in psychology, it is necessary to highlight the operational-algebraic structures of logic. The solution to this problem was given in a number of works by Piaget ( See J. Piaget. Classes, relations et nombres. Essai sur les groupements de la logistique et sur la reversibilite de la pensee. Paris, 1942; J. P i a-get. Traite de logique. Paris, 1949).

The most important role in these studies of J. Piaget is played by the concept of grouping, derived from the concept of group. In algebra, a group is understood as a set of elements that satisfy the following conditions: 1) the combination of two elements of the set gives new element given set; 2) each operation applied to the elements of the set can be undone by a reverse (inverse) operation; 3) set operations are associative, for example: (x+x")+y =x+(x"+y); 4) there is one and only one identical operator (0), which, when applied to an operation, does not change it, and which is the result of applying its inverse to a direct operation (x+0=x; x-x=0). The grouping is obtained if a fifth condition is added to the four group conditions: 5) the presence of a tautology: x+x=x; y+y=y.

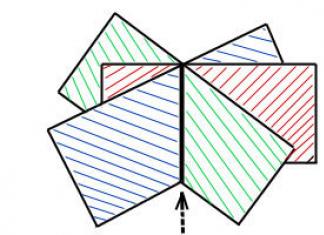

Let us consider, for example, a simple classification, where B is divided into A and not =A (A"), C into B and B", etc. Schematically, a simple classification can be represented as follows:

The laws of formation of simple classification are as follows:

The fulfillment of the first four conditions shows that simple classification represents a group. But it also fulfills a fifth condition, which can be interpreted as follows: the group operation “+” means the connection of all elements of two sets connected by this operation into one set, in which all elements appear once (if any element is contained in both sets, then this element appears in the resulting set only once). Based on what has been said, it is clear that A + A = A, because all the elements of the second set are contained in the first. Thus, a simple classification is a grouping, or more precisely, one of the elementary groupings of class logic.

Piaget establishes eight such elementary groupings of the logic of classes and relations. Each of these groupings has a precisely defined structure; Some of these structures are quite elementary (as in the example given with a simple classification), the rest are more complex. For relations there is a grouping (additive grouping of asymmetric relations), an isomorphic grouping of a simple classification. Let us characterize this group.

Let A->B be the relation “B is greater than A”, which is asymmetric and transitive. We will write it like this: A a -> B, where a is the difference between B and A; respectively: A b -> C, B a" -> C, C b" -> D, C c" -> D, etc.

The addition of asymmetrical relations forms a grouping:

Logical groupings of classes and relations represent, according to Piaget, certain structures that serve as a standard to which real operations of thinking “strive” at a certain level of their development (the so-called level of concrete operations). Psychologically, therefore, they can be considered as defining a form of equilibrium of the intellect. In this case, each grouping condition receives a corresponding psychological interpretation: the first condition speaks of the possibility of coordinating the actions of the subject, the second asserts a certain freedom of action direction (condition of associativity), the third (the presence of an inverse operation) - the ability to cancel the result of a previous action (what is in the intellect and what no, for example, in perception), etc.

According to Piaget, the subject's mastery of the corresponding logical operations is a criterion of his intellectual development. All eight groupings of the logic of classes and relations belong to Piaget’s so-called concrete operational level of intelligence development. A fourth level is built on top of it and from it is formed - the stage of formal operations, where the subject masters the logical connections that take place in the logic of statements.

In this regard, Piaget faces the question of the logical structures of this more high level development of intelligence - stages of formal operations. When studying this problem, carried out, in particular, in the “Logical Treatise”, Piaget came to the following conclusions ( See J. Piaget. Traite de logique, ch. V, Paris, 1949).

1. For each operation of the propositional calculus there is an inverse operation (N), which is a complement to the complete statement. Thus, for р∨q, whose normal form is pq∨pg∨pq, the operation pq will be inverse; for p⊃q - pq, etc.

2. For each operation there is a reciprocal operation (R), i.e. the same operation, but performed on statements of inverse signs: for p∨q - p∨, for pq-pq, etc.

3. For each operation there is a correlative operation (C), which is obtained by replacing in the corresponding normal form V sign to sign; and back. For p∨q the correlative operation will be p q, and vice versa.

4. Finally, if we add to N, R and C an identical operation (I), i.e., an operation that leaves the expression the same, then the set of transformations (N, R, C and I) form a communative group defined by the equalities

N=RC(=CR); R=NC(=CN); C⇔NR(=RN); I=RCN

or table

The RCNI group, however, does not cover the entire two-digit utterance count; it expresses only part of it. Piaget solves the problem of the logical organization of propositional calculus as a whole - the most important component of the stage of formal operations - by generalizing the concept of grouping introduced by him. In particular, he builds a special grouping that expresses the logical structure of propositional calculus ( See ibid., §§36-40). At the same time, Piaget shows that the two-valued logic of statements is based exclusively on the relationship of the part to the whole and the addition of the part to the whole. It, therefore, examines the relationship of the parts to each other, but only through the relationship to the whole and does not take into account the direct relationship of the parts to each other ( Ibid., pp. 355-356. See also: F. Kroner. Zur Logik von J. Pia-get.- "Dialectica", 1950, vol. 4, N 1).

The constructed logic gives Piaget an important criterion for psychological research. Once the logical structures of the intellect that must be developed in the individual have been established, the task of psychological research is now to show how, in what way this process occurs, what is its mechanism. In this case, logical structures will always act as the final links that must be formed in the individual.

Successive stages of intelligence formation

The central core of the genesis of intelligence, according to Piaget, is the formation of logical thinking, the ability for which, according to Piaget, is neither innate nor preformed in the human spirit. Logical thinking is a product of the growing activity of the subject in his relationship with the outside world.

J. Piaget identified four main stages of development of logical thinking: sensorimotor, pre-operational intelligence, concrete operations and formal operations ( When presenting the stages of development of intelligence, we rely mainly on the final work of J. Piaget and B. Inhelder: J. Piaget und B. Inhelder. Die Psychologic der friihen Kindheit. Die geistige Entwicklung von der Geburt bis zum 7 Lebensjahr. - In: "Handbuch der Psychologic" hrsg. D. und R. Katz. Basel - Stuttgart, 1960, S. 275-314).

I. Intellectual acts at the stage of sensorimotor intelligence (up to two years) are based on the coordination of movements and perceptions and are performed without any representation. Although sensorimotor intelligence is not yet logical, it forms a “functional” preparation for logical thinking itself.

II. Pre-operational intelligence (from two to seven years) is characterized by formed speech, ideas, internalization of action into thought (action is replaced by some sign: a word, an image, a symbol).

At one and a half years old, the child begins to gradually master the language of the people around him. However, initially the mutual relationship between designation and thing is still uncertain for the child. At first he does not form concepts in the logical sense. Its visual concepts, or “pre-concepts,” do not yet have any precisely described meaning. A small child does not conclude either deductively or inductively. His thinking is based primarily on conclusions by analogy. By the age of seven, a child thinks well visually, that is, he experiments internally with the help of ideas. However, in contrast to logical-operational thinking, these thought experiments remain irreversible. At the stage of preoperational intelligence, the child is not able to apply the previously acquired scheme of action with constant objects either to distant objects or to specific sets and quantities. The child lacks reversible operations and concepts of conservation applicable to actions at a higher level than sensorimotor actions. The child's quantitative judgments during this period, notes J. Piaget, lack systematic transitivity. If we take the quantities A and B, and then B and C, then each pair is recognized as equal - (A = B) and (B = C) - without establishing the equality of A and C ( J. Piaget. La psychologie de l'intelligence, p. 102).

III. At the stage of concrete operations (from 8 to 11 years), various types of mental activity that arose during the previous period finally reach a state of “moving equilibrium,” that is, they acquire the nature of reversibility. During this same period, the basic concepts of conservation are formed, the child is capable of logically specific operations. It can form both relations and classes from concrete objects. During this period, the child is able to: arrange sticks in a continuous sequence from smallest to largest or vice versa; accurately establish an asymmetric sequence (A “However, all logical operations at this age still depend on specific areas of application. If, for example, a child already at seven years old manages to arrange sticks along their lengths, then only at nine and a half years old is he able to perform similar operations with weights, and with volumes - only at 11-12 years old" ( J. Piaget und B. Inhelder. Die Psychologie der friihen Kindheit, S. 284). Logical operations have not yet become generalized. At this stage, children cannot construct logically correct speech regardless of real action. IV. At the stage of formal operations (from 11-12 to 14-15 years) the genesis of intelligence is completed. During this period, the ability to think hypothetically and deductively, theoretically, appears, and a system of operations of propositional logic (logic of statements) is formed. With equal success, the subject can now operate with both objects and statements. Along with the operations of propositional logic, during this period the child develops new groups of operations that are not directly related to the logic of statements (the ability to perform combinatorial operations of any kind, to operate broadly with proportions); operational schemes arise related to probability, multiplicative compositions, etc. The appearance of such systems of operations indicates, according to J. Piaget, that the intellect is formed. Although the development of logical thinking forms the most important aspect of the genesis of intelligence, it, however, does not completely exhaust this process. In the course and on the basis of the formation of operational structures of varying complexity, the child gradually masters the reality around him. “During the first seven years of life,” write Piaget and Inelder, “the child little by little discovers the elementary principles of invariance relating to object, quantity, number, space and time, which give his picture of the world an objective structure” ( J. Piaget und V. Inhelder. Die Psychologic der fruhen Kindheit, S. 285). The most important components in the interpretation of this process proposed by Piaget are: 1) analysis of the child’s construction of reality depending on his activity; 2) the spiritual development of the child as an ever-increasing system of invariants he masters; 3) the formation of logical thinking as the basis of all intellectual development of the child. Piaget, together with his collaborators, subjected many aspects of this process to a detailed experimental analysis, the results of which are presented in a series of monographs. Without being able to go into the intricacies of these studies, we will give a summary of the results of these studies. The formation in a child of the concept of an object and the basic physical principles of invariance goes through the same four main stages as in the case of the development of logical thinking. At the first stage (sensorimotor intelligence), the formation of a sensorimotor scheme of an object occurs. Initially, the world of children's ideas consists of images that appear and disappear; there is no constant subject here (first and second stages). But gradually the child begins to distinguish known situations from unknown ones, pleasant from unpleasant. During the second stage (pre-operational intelligence), the child develops a visual concept of set and quantity. He is not yet able to apply the previously acquired scheme of action with a constant object either to individual objects or to sets and quantities. Multiple objects (for example, a mountain) appear to the child of this phase to increase or decrease depending on their spatial location. If a child is given two plasticine balls of equal shape and mass and one of them is deformed, then he believes that the amount of matter has increased (“the ball has now become so long”) or decreased (“it is now so thin”). Thus, children at this stage deny both the invariance of matter and the invariance of quantity of matter. At the stage of operational-concrete thinking, the child forms logical-operational concepts of set and quantity. This process ends at the stage of formal operational intelligence. During this period, the child is able to mentally convert the perceived changes in Multitude and Quantity; Thus, he confidently asserts that, despite the change in shape, there is an equal amount of plasticine (in the example just discussed). This is the result of operations of thinking, more precisely, the coordination of reversible relations ( See ibid., p. 288). In a similar way, Piaget traces the process of a child’s mastery of the concepts of number, space, and time. The main thing in this genesis is the formation of certain logical structures, and on their basis - the possibility of constructing a corresponding concept. In this case, the experimental technique usual for Piaget is used: special tasks are selected for children, the degree of their mastery of these tasks is established, then the task is complicated in such a way that it makes it possible to establish the next stage of the child’s spiritual development. On this basis, the entire analyzed process is divided into phases, stages, substages, etc. So, for example, when analyzing the genesis of number in a child, it is established that the arithmetic concept of number is not reduced to individual logical operations, but is based on the synthesis of the inclusion of classes (A+A"=B) and asymmetric relations (A In his research, J. Piaget considers not only the actual development of intelligence in a child, but also the genesis of his emotional sphere. Feelings are viewed by Piaget (as opposed to Freud) as developing, as a result of active spiritual construction. In this regard, the genesis of feelings falls into three phases, corresponding to the main phases of the development of intelligence: sensorimotor intelligence corresponds to the formation of elementary feelings, visual-symbolic thinking corresponds to the formation of moral consciousness, which depends on the judgment of adults and on the changing influences of the environment, and, finally, logically specific thinking corresponds to the formation of will and moral independence ( J. Piaget. Le jugement moral chez l "enfant. Paris, 1932). During this last period, life in children's society develops independence of moral judgment and a sense of mutual responsibility. Piaget especially emphasizes the fact that “the will develops together with moral independence and the ability to think consistently logically.” “The will really plays a role in the sensory life of a child similar to the role of thinking operations in intellectual cognition: it maintains balance and constancy of behavior” ( J. Piaget und B. Inhelder. Die Psychologic der fruhen Kindheit, S. 312). Thus, a single principle of analysis is consistently applied through the entire system. We have outlined the basic principles of J. Piaget's psychological concept. Let us now move on to consider the issues that arise in connection with the interpretation of the operational concept of intelligence. Attempts to construct such interpretations have appeared ( See A.G. Comm. Problems of the psychology of intelligence in the works of J. Piaget; V. A. Lektorsky, V. N. Sadovsky. The main "ideas of" genetic epistemology" by J. Piaget. - "Questions of Psychology", 1961, No. 4, etc.), and it is natural to assume that work in this direction will continue. Below we will try to offer an interpretation of a number of important aspects of Piaget's concept. To construct an interpretation of the operational concept of intelligence means, firstly, to reconstruct its subject, secondly, to establish the fundamental results obtained in the course of its development, and, thirdly, to correlate the theoretical representation of the subject studied by J. Piaget with the modern understanding of this object. To reconstruct the subject studied in the operational concept of intelligence, it is necessary to highlight the starting point of J. Piaget’s psychological research. As such, as already noted, is the task of analyzing the mental development of an individual depending on changes in the forms of social life. Schematically, this subject of research can be represented as follows: where ⇓ means the direct impact of various forms of social life on individual mental development. Regarding the subject of research highlighted in diagram (1), it is necessary to emphasize the following. 1. From the very beginning, the mental development of an individual is understood by J. Piaget, firstly, as a certain specific form of activity and, secondly, as something derived from external non-mental (objective) activity. 2. In real research (as, for example, it was carried out in the first books of J. Piaget), it is not the entire structure depicted in diagram (1) that is analyzed, but its relatively narrow “slice”. 3. When studying a subject (1), the understanding of the psyche as a specific activity derived from objective activity, being accepted in principle, is actually replaced by consideration of only verbal activity (children's conversations), which, as we know, Piaget himself was soon forced to abandon. Distracting for now from the fact of the evolution of Piaget's concept (i.e., from the modification of the subject studied within the framework of this concept), we consider it necessary to pay special attention to the original structure, the analysis of which J. Piaget tried to give in his first works. Isolation of the subject (1) in as an object of psychological analysis, Piaget is at the forefront of contemporary psychological science. Moreover, this structure contains all the fundamental elements necessary for constructing the psychology of thinking from the point of view of today’s theoretical concepts in this regard. Particular mention should be made of the awareness of the fact that mental development depends on changes. social reality and the principle of activity, i.e., understanding the psyche not as some static internal state of the individual, but as a product of a special form of activity of the subject. However, having set structure (1) as the initial subject of research, Piaget essentially found himself in an insoluble (at least for the period of the 20s) situation. The fact is that such a subject of research is an extremely complex structural formation, research methods for which are not sufficiently developed today. The success of the analysis of the subject (1) is possible only in the case of constructing detailed theories of the genesis of mental functions and the evolution of forms of social activity, and on this basis - a detailed representation of the ways in which social reality influences the individual’s psyche. Piaget had neither the first, nor the second, nor the third. At that time he did not have a specific apparatus for analyzing each of these components. In this situation, it seems quite natural for Piaget to make the transition from the original subject of research to its significant modification, much simpler in structure and therefore amenable to detailed analysis. This modification concerned primarily three points: 1. The connection between the generation of mental states of the individual by forms of social activity is replaced by the relationship of mutual expression of the first in the second, and vice versa. 2. To strictly represent the various stages of an individual’s intellectual development, the apparatus of modern formal logic is used in such a way that logical structures correspond to certain intellectual structures identified in psychology, and vice versa. As a result of this, a relationship of mutual expression is established not only between mental and social structures, but also between social structures and logical structures. 3. In genetic terms, intellectual structures are generated by external objective actions; for its part, the form of organization of intellectual structures expresses in a clear form the organization to which the structures of external objective actions strive, in other words, the structure of systems of external actions anticipates (expresses in implicit form) the logical organization of the intellect. Taking into account these modifications, we can give the following image of the subject of research in the works of J. Piaget: In diagram (2), the arrow ↔ depicts the relationship of mutual expression of one component of an object in another, dotted arrow --> characterizes the relationship between systems generating external actions of intellectual structures, and the arrow ⇒ indicates the area of science from which Piaget in his research proceeds when constructing, in one case, the theory of logical structures, and in the other, the theory of the genesis of intelligence. The multicomponent structure (2) is largely imaginary. By introducing the relationship of mutual expression, J. Piaget essentially reduces structure (1) to an object in which each component is only a different form of expression of the other, i.e., to an object in which there are only different expressions of the same structure. This actually simplifies the subject of analysis; it is reduced to a structure that lends itself - to modern level development - detailed research. To understand the position defended by Piaget on the relationship between social structures and structures of the intellect (both logical and actually mental), it is extremely interesting to pay attention to his formulation of this problem in the book “Psychology of Intelligence”. The question here is posed as follows: is logical grouping a cause or a result of socialization? ( See J. Piaget. La psychologie de l'intelligence, p. 195) According to Piaget, two different, however, complementary answers should be given to this question. First, it must be noted that without the exchange of thoughts and without cooperation with other people, an individual would never be able to co-organize his mental operations into a single whole - “in this sense, operational grouping presupposes social life” ( Ibid.). But, on the other hand, the exchange of thoughts itself is subject to the law of equilibrium, which is nothing more than a logical grouping - in this sense, social life presupposes a logical grouping. Thus, grouping acts as a form of equilibrium of actions - both interindividual and individual. In other words, a group is a certain structure that is contained in both individual mental and social activity. That is why, Piaget continues, the operational structure of thought can be isolated both from the study of the individual’s thought at the highest stage of its development and from the analysis of the methods of exchange of thoughts between members of society (cooperation) ( See J. Piaget. La psychologica de l'mtelligence, p. 197). “Internal operational activity and external cooperation... are only two additional aspects of one whole, that is, the equilibrium of one depends on the equilibrium of the other” ( Ibid., p. 198). The central link of the subject presented in diagram (2) undoubtedly lies in the nature of the relationship between logical and real mental structures. This problem and the method of solving it, proposed in the operational concept of intelligence, express the most specific features of J. Piaget’s approach to the study of the psyche. If structure (1) is adopted, the researcher has two possible ways of further analysis - either in terms of elucidating the impact of forms of social activity on individual mental development (which, as we found out, significantly exceeded the real capabilities of psychology in the 20-30s), or in the direction of uncovering the patterns of “internal” mental activity. The transition to structure (2) indicates that Piaget solves the problem in favor of the second term of the alternative, which inevitably raises the question of the apparatus of such research. Like any specifically scientific research, Piaget's analysis of the psychology of the development of intelligence is based on some - perhaps not always clearly formulated - premises. In this regard, we should first of all mention the concretization of the idea of intellect as activity (intelligence as a certain set operations, i.e. acceptance of the thesis that operation is an element of activity). The next step is to define what the operation is. This issue is resolved by attributing the operation to some integral system, only as a result of entering into which the action is an operation. Finally, the last prerequisite is to adopt a genetic approach to the analysis of intellectual activity as various systems of operations. The indicated prerequisites for Piaget’s psychological research represent a certain abstraction from the experimental material accumulated in the thinking of psychology (including in the works of Piaget), and as such they should act as a means of further theoretical analysis. But at the same time - and this is no less obvious - these principles are not directly contained in the experimental psychological material itself: the process of identifying them (and especially further development) is necessarily connected with the involvement of a special apparatus, which may not be directly related to psychology child, but, however, must be able to clearly express these principles and have sufficient “capacity” to specify them. Now we can clearly formulate, following J. Piaget, the main premises of his approach to the analysis of the psychology of intelligence only because the author of this concept “found” such an apparatus, and the choice turned out to be very promising. Thus, in terms of the formation of the very concept of J. Piaget, the following relationship between its logical and psychological aspects took place: The logical structures included in the operational concept of intelligence represent a special reformulation of the content of certain sections of formal logic. The nature of this reformulation is determined, however, not only and not so much by the corresponding formal logical theories, but by the structure of those intuitively distinguished mental structures, a special way of describing which logical structures should ultimately act. Therefore, when constructing Piaget’s concept, along with the relation “formal logic ⇒ logical structures,” the most important role was played by the influence of intuitively identified mental structures on the formulation of the theory of logical structures so that subsequently - after constructing the basis of the theory - these latter acted as a description apparatus (and not an intuitive idea) of the former. A similar mechanism for the formation of the concept led to the fact that in the created theory a relationship of mutual expression was established between logical and psychological structures. A “formed” theory removes the processes that led to its creation, and leaves only the final result - the correspondence of one structure to another. In this regard, how is the problem of the status of logic and the psychology of thinking solved within the framework of Piaget’s concept? In contrast to various interpretations of the subject of logic, which refuse it to be a way of describing thinking - platonism, conventionalism, etc. ( See J. Piaget. Logic and psychology. Manchester, 1953), Piaget puts forward the thesis that both traditional and modern formal logic ultimately describe certain patterns of thinking. Depending on the method of construction, the degree of formalization, and axiomatization, the relevance of logical systems to the real process of thinking varies. This relationship is very indirect in the case of, for example, axiomatic calculi of modern formal logic and is significantly closer to the operational interpretation of logic. To the extent that psychology analyzes the final states of equilibrium of thought, there is, Piaget argues, a correspondence between psychological experimental knowledge and logistics, just as there is a correspondence between a diagram and the reality that it represents ( See J. Piaget. La psychologica de 1"intelligence, p. 40). At the same time, the partial parallelism between logic and psychology does not mean that logical rules are psychological laws thoughts, and one cannot without ceremony apply the laws of logic to the laws of thought ( J. Piaget, E. Beth, J. Dieudonne, A. Lichnerowicz, G. Choquet, C. Gattengo. L'enseignement des Mathematiques. Neuchatel - Paris, 1955). Thus, there is no parallelism between logic and psychology, taken literally. The relationship of mutual expression and correspondence of logical structures takes place only for those final states of equilibrium that are formed in the course of individual mental development. In all other respects, the psychology of thinking and logic belong to different areas and solve problems that differ from each other. Based on the above, it is necessary to add the following specification to structure (2) (we take only one fragment of the whole subject): Logical structures S 1 S 2, S 3 .... included in the operational concept of intelligence, represent a set of algebraic formations between which logical-mathematical relationships are established, ultimately based on the use of deductive inference techniques. Thus, there is nothing specifically psychological in this area. Structures S 1 , S 2 , S 3 ,... describe certain ideal conditions of equilibrium and as such correspond (with proper psychological interpretation) to the real intellectual structures S 1 ", S 2 ", S 3 ",... formed during genetic development. Particular parallelism, or more precisely, mutual expression, the correspondence of some “final products” - this is the real meaning of the connection between logic and psychology in the works of J. Piaget. There is no doubt that the idea of the unity of psychological and logical research is the most important merit of J. Piaget and his significant contribution to the development of the psychology of thinking ( See V. A. Lektorsky, V. N. Sadovsky. The main ideas of "genetic epistemology" by Jean Piaget. - "Questions of Psychology", 1961, No. 4, pp. 167-171, 176-178; G. P. Shchedrovitsky. The place of logic in psychological and pedagogical research. - "Theses of reports at the II Congress of the Society of Psychologists", vol. 2. M., 1963). Only as a result of widespread involvement in psychological research logical apparatus, Piaget was able to make great progress in analyzing the most important problems of modern psychology: the idea of activity and the genesis of the psyche, issues of the derivative of intellectual structures from external objective actions and the systematic nature of mental formations. It is well known that the concept of activity underlies many modern psychological interpretations of thinking. However, as a rule, this concept is taken as intuitively obvious and further undefined, which inevitably leads to the fact that it essentially drops out of the analysis. Piaget, starting with such an intuitively accepted concept of activity, then through the prism of his logical apparatus introduced a certain rigor and certainty into this concept. The logical apparatus in his concept serves precisely to give a breakdown of activity and turn this concept into a valid means of psychological analysis. But, following the path to achieving this goal, Piaget - due to the logical apparatus he uses - gives only an extremely one-sided representation of activity. The activity analyzed within the framework of the operational concept of intelligence is an object constructed on the basis of the application of logical structures, and as such, on the one hand, it can be analyzed within the framework of the possibilities inherent in psychologically interpreted logical structures, and on the other, in no way can serve as a depiction of the activity as a whole. After all, even for Piaget himself, logic is just some ideal scheme that never represents reality in its entirety. This was very clearly manifested in the nature of J. Piaget’s genetic research. To reveal the causal mechanism of genesis, this means, according to Piaget, “firstly, to restore the initial data of this genesis... and, secondly, to show how and under the influence of what factors these initial structures are transformed into the structures that are the subject of our research "( J. Piaget and B. Inelder. Genesis of elementary logical structures. M., 1963, p. 10). Giving a more detailed presentation of the criteria for genetic analysis, B. Inelder writes that the development of intelligence goes through a number of stages. In this case: 1) each stage includes a period of formation of genesis and a period of “maturity”; the latter is characterized by a progressive organization of the structure of mental operations; 2) each structure is at the same time the existence of one stage and the starting point of the next stage, a new evolutionary process; 3) the sequence of stages is constant, the age of reaching one or another stage varies within certain limits depending on the experience of the cultural environment, etc.; 4) the transition from early stages to later ones is accomplished through special integration: previous structures turn out to be part of subsequent ones ( V. Inhelder. Some aspects of Piaget's genetic approach to cognition. - In: "Thought in the Young Child", p. 23). What actually results from research built on such principles? Fixation of the successive stages that, according to this concept, a child goes through in his development, both in the field of logical thinking and mastery of reality, and in the field of affective life. The only working criterion in this case is again logical structures. They not only correspond to real mental structures, but also predetermine - at each stage of development - what should be formed in the individual. Genetic research of intelligence, thus, acts as a fixation of the stages of achieving the corresponding logical structures. As a result of this, the analysis of the internal mechanisms of the development process falls out of the study, and genetic consideration, at best, gives an idea of pseudogenesis, built in accordance with the requirements arising from a system of logical structures. The same difficulty, but in a slightly different form, appears when considering the process of generation of primary intellectual structures by external objective actions. Sensorimotor intelligence, according to Piaget, is an undeveloped form of balance. But in this case, as A. Vallon noted, there is an error in anticipating the investigation. Unable to derive intelligence and personality from the system of actions, Piaget, according to Vallon, introduced intellectual structures into the actions themselves ( See A. Vallon. From action to thought. M., 1956, pp. 43, 46-50). To a large extent this argument is valid. It, of course, should not be understood in the sense that the very idea of deriving intellectual structures from sensorimotor is false. The systematic consideration of this possibility is the most important positive part of Piaget's work. The point is different - normative logical requirements here act as the only real research principle, thereby reducing genetic analysis to a deliberately one-sided pseudogenetic reconstruction. Great difficulties remain for Piaget in his interpretation of intelligence as a system of operations. Piaget shares with a number of other modern researchers the merit of putting forward the problem of systematicity as one of the central problems of science. He also did a lot on the concrete application of this idea to the analysis of the psyche. Piaget repeatedly emphasizes the idea of constructing a “logic of integrity” in the form of logical-algebraic structures: “... it is necessary to construct a logic of integrity if one wants it to serve as an adequate scheme for equilibrium states of the spirit, and to analyze operations without returning to isolated elements that are insufficient from the point of view of psychological requirements" ( J. Piaget. La psychologie de l'intelligence, p. 43; J. Piaget. Methode ixiomatique et metiiode operationnelle. - "Synthese", vol. X, 1957, No. 1). The algebraic apparatus used by Piaget in this regard undoubtedly acts, to a certain extent, as a systematic alternative in relation to atomized axiomatics. Group, grouping and other algebraic structures define elements, their connections and relationships depending on the whole. But it is obvious that in the case of algebraic systems we are dealing with a very narrow and simplest class of system formations. Piaget sees intelligence only through the prism of these algebraic structures, the inadequacy of which in terms of analyzing mental activity does not even require detailed justification. Thus, the extremely important problem of the systematic nature of mental functions received the first real results from Piaget, which, however, essentially led to the need for a new “approach” in its analysis. Concluding the consideration of the interpretation of the psychological theory of J. Piaget, it is necessary to emphasize that the reconstruction of the subject studied in this theory helped us to establish both the real area being analyzed and the conceptual apparatus used for this, as well as the main difficulties in constructing the psychology of thinking that J. could not overcome Piaget. We can obtain additional considerations on this matter in the course of analyzing the principles of “genetic epistemology.” Propositional, or formal, operations (from 11-12 to 14-15 years). The last period of operational development begins at the age of 11-12 and leads to a state of equilibrium at the age of 14-15, when the child develops the logic of an adult. At the fourth stage of operational development, a new property appears - the ability to think with hypotheses.

Such hypothetico-deductive reasoning is characteristic of verbal thinking, characteristic, among other things, from the point of view that it creates the opportunity to accept any data as something purely hypothetical and build reasoning around them. Let us imagine, for example, that a child was given the following series of meaningless sentences from the Ballard test to read: I am very glad that I do not eat onions, because if I like them, I will have to always eat them, and I hate eating unpleasant ones. things. If this child is at the level of concrete thinking, then he will begin to criticize the initial premises: onions are not unpleasant, it is wrong not to like them, etc. But if he is at the level we are considering, then he accepts these premises without discussion and simply points out the contradiction between I love them and the bulbs are unpleasant. A subject of this level operates with hypotheses not only verbally. The new ability that has emerged has a profound effect on his behavior in laboratory experiments. When he is given one of the devices that my colleague B. Inelder used in her research physical output, he acts with it in a completely different way from how the subject acted at the level of concrete thinking. For example, when given a pendulum and allowed to change the length and amplitude of its oscillations, its weights and initial impulses, then subjects aged 8 to 12 years simply randomly select facts, classify them, build series and establish correspondences between the achieved results. Subjects between the ages of 12 and 15 try, after a few trials, to formulate all possible hypotheses about the factors that need to be taken into account, and then order their experiments as a function of these factors. This new attitude gives rise to a number of consequences. Firstly, in order to establish or verify the actual relationships between objects, thought no longer moves from the actual to the theoretical, but immediately begins with theory. Instead of an exact coordination of facts relating to the actual world, hypothetico-deductive reasoning builds conclusions from possible positions and, thus, leads to a general synthesis of the possible and necessary. Jean Piaget, Psychology of Intelligence / Selected Psychological Works. Psychology of intelligence. Genesis of number in a child. Logic and psychology, M., Education, 1969, p. 587-588. .Piaget. ; (from 2 to 7 years) and (from 7 to 11 years); period of formal operations. Definition of Intelligence Intelligence The main stages of development of a child’s thinking Piaget identified the following stages of development of intelligence. 1) Sensorimotor intelligence (0-2 years) During the period of sensorimotor intelligence, the organization of perceptual and motor interactions with the outside world gradually develops. This development goes from being limited by innate reflexes to the associated organization of sensorimotor actions in relation to the immediate environment. At this stage, only direct manipulations with things are possible, but not actions with symbols and ideas on the internal plane. Preparation and organization of specific operations (2-11 years) · Sub-period of pre-operational ideas (2-7 years) At the stage of pre-operational representations, a transition is made from sensorimotor functions to internal - symbolic ones, that is, to actions with representations, and not with external objects. This stage of intelligence development is characterized by the dominance of preconceptions and transductive reasoning; egocentrism; centralization on the striking features of an object and neglect in reasoning of its other features; focusing on the states of a thing and not paying attention to it transformations. · Sub-period of specific operations (7-11 years) At the stage of concrete operations, actions with representations begin to unite and coordinate with each other, forming systems of integrated actions called operations factions(For example, classification Formal Operations (11-15 years) The main ability that emerges during the formal operations stage (from about 11 to about 15 years of age) is the ability to deal with possible, with the hypothetical, and perceive external reality as a special case of what is possible, what could be. Cognition becomes hypothetico-deductive. The child acquires the ability to think in sentences and establish formal relationships (inclusion, conjunction, disjunction, etc.) between them. A child at this stage is also able to systematically identify all the variables essential to solving a problem and systematically go through all possible combinations these variables. Basic mechanisms cognitive development baby 1) assimilation mechanism: an individual adapts new information (situation, object) to his existing patterns (structures), without changing them in principle, that is, he includes a new object in his existing patterns of actions or structures. 2) the mechanism of accommodation, when an individual adapts his previously formed reactions to new information (situation, object), that is, he is forced to rebuild (modify) old schemes (structures) in order to adapt them to new information (situation, object). According to the operational concept of intelligence, the development and functioning of mental phenomena represents, on the one hand, assimilation, or assimilation of this material by existing behavioral patterns, and on the other, the accommodation of these patterns to a specific situation. Piaget views the adaptation of the organism to the environment as a balancing of subject and object. The concepts of assimilation and accommodation play a major role in the explanation of the genesis of mental functions proposed by Piaget. Essentially, this genesis acts as a sequential change of various stages of balancing assimilation and accommodation .