White armor- This is the armor of the late XIV-early XV centuries.

White armor is any armor that is a natural metal color.

White armor - any armor that is not blued, covered with fabric or painted.

White armor (English white armor, German alwite) - the first and early full armor, late XIV-early XV centuries, named to distinguish them from brigantines. They evolved in Italy into the “pot-bellied” Milanese armor, and in Germany into the angular caste-breast.

Early armor, called white armor, shows similarities with both Milanese armor and caste-breast, while in appearance they are more similar to Milanese armor, and in the way the upper part of the cuirass breastplate is connected to its lower part, they are more similar to caste-breast . Dividing the cuirass breastplate into two large segments allows for bending and unbending. In Milanese armor it is located on top of its upper part, while in white armor the lower part of the breastplate (if there was one) was located, as in the caste-breast, under the upper part. Moreover, depending on the region, the cuirass could be either round, like the Milanese armor, or with a “sagging” chest (convex at the bottom), like a cast-in-breast, but without the angularity inherent in a cast-in-brest.

The plate skirt (belly) was similar to the Milanese one, but without thigh guards (tassets), also the caste-breasts were characterized by a very long plate skirt, but some variants had a short skirt. Unlike Milanese armor and caste-breasts, white armor was worn not with plate gauntlets, but with plate gloves. The grand bascinet was usually worn as a helmet - a reliable helmet resting on the shoulders, characteristic of both caste-breasts and Milanese armor in the Italic style. alla francese (a la French). But at the same time, the visor of the grand bascinet often had not the classic round shape, but the pointed shape of a Hundsgugel, again combined with a pointed nape, instead of a round one.

Complete early armor, unfortunately, has not survived to this day, and individual surviving parts can also be interpreted as parts of early Milanese armor.

Such armor was made throughout the 15th century and reached its peak in the 1480s, when it was considered the best in Europe. Their appearance bore the features of Gothic architecture and Gothic art. The armor had many pointed shapes and graceful lines, in addition, as a rule, this type of armor had corrugations and corrugations - the so-called stiffening ribs, which increased the strength of the armor. As a rule, Gothic armor used a salad with a long and sharp backplate, which protected the back of the neck and head. Bouviger protected his chin. In addition to steel plates, these armors included chainmail elements attached to the underarmor to protect the body at the inside of the joints and crotch.

Sometimes this type of armor is called German Gothic, and the contemporary Milanese armor is called Italian Gothic, on the basis that outside of Germany and Italy, Italian and German parts of armor were sometimes mixed (this was especially often done in England), resulting in armor that had mixed features. The argument against this use of terminology is that Milanese armor existed (with minor design changes) both before and after Gothic armor (Gothic armor existed from the middle of the 15th century, and in the early years of the 16th century - before the appearance of Maximilian armor, and Milanese armor with end of the 14th century and continued to be worn at the beginning of the 16th century).

By style, Gothic armor is divided into high and low Gothic, as well as late and early. About some misconceptions:

Some people mistakenly believe that Gothic armor is characterized by the absence of tassets, but in fact this is a feature of the most famous examples - there are lesser known examples of Gothic armor in which tassets are not lost.

It is usually believed that high Gothic must have abundant fluting, but there are examples of high Gothic that have the characteristic silhouette of high Gothic, but do not have fluting (in particular, these are found both among those forged by Prunner and among those forged by Helmschmidt, who were at that time one of the most famous armor smiths).

Late Gothic and high Gothic are not the same thing; cheap examples of late Gothic sometimes have signs of low Gothic.

AND Talian armor of the late 14th - early 16th centuries, sometimes called “Italian Gothic”. The export version was called alla francese (ala French) and had a grand bascinet helmet and pointed sabatons. A characteristic difference from the German “Gothic” was its smooth, rounded shape, a cuirass fastened with belts, shoulder pads and elbow pads of different sizes (the left one is much larger), and the use of plate gauntlets to protect the hands (in German armor, plate gloves were mainly used).

AND Talian armor of the late 14th - early 16th centuries, sometimes called “Italian Gothic”. The export version was called alla francese (ala French) and had a grand bascinet helmet and pointed sabatons. A characteristic difference from the German “Gothic” was its smooth, rounded shape, a cuirass fastened with belts, shoulder pads and elbow pads of different sizes (the left one is much larger), and the use of plate gauntlets to protect the hands (in German armor, plate gloves were mainly used).

German armor of the first third of the 16th century (or 1505-1525, if characteristic corrugation is considered mandatory), named after Emperor Maximilian I.

German armor of the first third of the 16th century (or 1505-1525, if characteristic corrugation is considered mandatory), named after Emperor Maximilian I.

The armor is characterized by the presence of an armet-type helmet and a closed helmet with a corrugated visor, fine fan-shaped and parallel corrugations, often covering most of the armor (but never the greaves), engraving, a strongly convex cuirass, and peculiar blunt-nosed sabatons.

The armor itself was designed to emulate the pleated clothing that was fashionable in Europe at the time. The creation of armor that not only provided the maximum level of protection, but also was visually attractive was a trend in Europe in the 15th and 16th centuries. She combined the Italian rounded style of armor with the German fluted style.

Maximilian armor is indeed somewhat similar to Italian armor in the Italic style. alla tedesca (ala Germanic), but created in Germany/Austria under the influence of Italian armor, famous for its reliability and protection (in return for sacrificing freedom of movement). With external outlines that make it similar to Milanese armor (adjusted for the different curve of the cuirass), it has design features inherited from German Gothic armor. The abundance of stiffening ribs (made by embossing) gave a more durable structure, which made it possible to reduce the thickness of the metal and significantly reduce weight! At the same time, the armor, unlike the Gothic, like the Milanese, was made not from small, but from large plates, which is associated with the spread of firearms, which is why it was necessary to sacrifice the famous flexibility and freedom of movement of the Gothic armor for the sake of the ability to withstand a bullet fired from a distance . Due to this, a knight in such armor could be reliably hit from the hand-held firearms of that time only by shooting at point-blank range, despite the fact that very strong nerves were needed in order not to prematurely shoot at an attacking knight on an armored horse, which could trample without resorting to weapons . Also playing a role was the low accuracy of the firearms of that time, and the fact that they fired with a slight and, most importantly, almost unpredictable delay (the gunpowder on the seed shelf does not ignite and burn instantly), which made it impossible to target the vulnerable spots of a moving rider.

In addition to creating stiffening ribs by corrugation, another method of creating stiffening ribs was widely used in Maximilian armor. The edges of the plates were bent outward and wrapped into tubes (along the edges of the armor), which in turn, through additional corrugation, were shaped in the form of ropes, as a result of which the plates received very strong stiffening ribs along the edges. It’s interesting that the Italians have Ital. alla tedesca (a la Germanic) the edges of large plates also curved outward, but were not always wrapped. In Gothic armor, instead of arching, the edges of the plates were corrugated and could have a riveted gilded edging as decoration.

The term "Maximilian armor" does not mean that every armor worn by Maximilian I is Maximilian. The most famous armor worn by Maximilian was not Maximilian, but the Gothic armor worn by Maximilian when he was a young prince and later presented as a noble wedding gift for his uncle Sigmund. Maximilian I became Emperor in 1493 and died in 1519, but classic Maximilian armor is known from 1515 to 1525, and similar shaped armor with less or different fluting is known from 1500.

Transitional Scott-Sonnenberg style

Early types of this armor, which were not fluted or had wolfzahne ("wolf teeth") style fluting (which differs from the classic Maximilian fluting style), and could be worn with a sallet, are distinguished from Oakeshott's typology into Scott-Sonnenberg style armor. According to Oakeshott, such transitional armor was worn from 1500 to 1520, and true Maximilian armor was worn from 1515 to 1525. However, some other historians trace the Scott-Sonnenberg style from the Maximilian armor.

Italian “alla tedesca” (“a la German”) armor

Italian “alla tedesca” (“a la German”) armor is Italian armor from 1500 to 1515 with a fluted and Maximilian-shaped chest, knee-length thigh guards, often worn with a salat with an accordion-type visor. This type of armor is considered by Oakeshott to be a type of Scott-Sonnenberg style armor made by the Italians for the German market.

A characteristic feature of Maximilian armor is considered to be plate gauntlets, capable of withstanding a blow to the fingers with a sword, but with the spread of wheeled pistols, Maximilians with plate gloves appeared that allowed them to shoot pistols. At the same time, although the plate gauntlets consisted of large plates, these plates were still somewhat smaller than in the Milanese armor, and their number was greater, which provided a little more flexibility with approximately equal reliability. In addition, the thumb protection corresponded in design to the thumb protection of Gothic armor and was attached to a special complex hinge that ensured greater mobility of the thumb.

Another characteristic feature is the “Bear Paw” sabatons (plate shoes), corresponding to the very wide-toed shoes fashionable at the time, from which the expression “living large” came. Later, after going out of fashion, these sabatons and shoes were nicknamed “Duck Paws.”

One of the most notable features that catches the eye is the visor, which had the following shapes:

“Accordion” (English bellows-visor) - a ribbed visor made of horizontal ribs and slits.

“Sparrow beak” (eng. sparrow beak) is a classic pointed-nosed form of visor, which was widespread over two centuries - in the 15th-16th centuries.

Classic design with a single visor.

A design that appeared in the 20s of the 16th century, in which the “beak” is divided into upper and lower visors, so that you can tilt up the upper visor (“open the beak”), improving visibility, with the lower visor lowered (naturally, such a visor was found only among the later Maximilians) .

“Monkey face” (English monkey-face), also known as “pug-nose” (English pug-nose) - having a protruding volume below the optic slits, similar to a radiator)))

“Grotesque” (English grotesque) - a visor that is a grotesque mask in the form of a human face or the muzzle of an animal.

The helmet itself had corrugation and a stiffening rib in the form of a low ridge. As for its design, there were four options for protecting the lower part of the face:

with a chinrest that flips up like a visor, and is often attached to the same hinge as the visor;

with a chinrest that was not hinged, but simply fastened in front;

with two cheekpieces closing with each other at the chin like doors (the so-called Florentine armet) in which the lower part of the helmet consisted of left and right halves that folded upward like a bomb bay, when closing they closed with each other in front and with a relatively narrow backplate at the back.

In Germany, the most popular option was the one with a folding chinrest and the slightly less popular option with two cheekpieces, while in Italy options were popular in which the protection of the lower part of the face consisted of left and right parts. In addition, the version with a folding chinrest did not need a disk sticking out like a nail with a huge head from the back of the head, and designed to protect against cutting (with a blow to the back of the head) the belt that holds the lower part of the helmet together.

Throat and neck protection - gorje (plate necklace) existed in two versions:

In fact, consisting of a traditional chinrest and backrest attached to the helmet. Unlike the design of the 15th century, the chinrest is not rigidly attached to the cuirass and closes with the backplate, forming a continuous armored neck protection, under which there is a real gorje; so it turned out to be two movable cones.

The so-called Burgundy, which provides the best protection for the neck of the head: a flexible gorge, consisting of plate rings, capable of tilting in any direction. A freely rotating helmet is attached to it using a characteristic fastening in the form of two hollow rings (often made like twisted ropes), freely sliding one into the other.

The increase in the plates of German armor, which led to the appearance of maximilians, was also accompanied by an increase in the size of the shoulder pads, as a result of which the need for the mandatory presence of a pair of rondels (round discs to protect the armpits) was eliminated. As a result, in addition to Maximilians with a traditional pair of rondels, there were also Maximilians with only the right rondel covering the cutout in the shoulder pad for the spear, since the left shoulder pad completely covered the armpit in front. As for the Maximilians without rondels, there is no consensus whether they had a right rondel (which was later lost), or no rondels at all.

Armor for ceremonial trips and ceremonies. It could be unsuitable for combat; in Europe it was often used as tournament armor at the same time.

Armor for ceremonial trips and ceremonies. It could be unsuitable for combat; in Europe it was often used as tournament armor at the same time.

The only known armor of the early Middle Ages that has survived to this day is the cataphract armor, it belonged to the Sarmatian king, made of pure gold (and therefore unsuitable for battle).

In Mesoamerica (pre-Columbian Central America), armor was unknown, but the rulers were dressed in gold, which, in addition to decorative purposes, provided some protection from weapons in case of danger, and can, with some degree of convention, be called ceremonial armor.

In Japan, as ceremonial armor, it was very prestigious to wear antique family armor that had been in some famous battle. Some of the expensive armor was for intimidation, covered entirely in bearskin and adorned with huge buffalo horns. During the reign of the regents from the house of Hojo (when there were no wars), lamellar armor made of elaborately small plates was fashionable, which, although not considered ceremonial, could nevertheless be called ceremonial due to its extreme cost and pretentiousness. Moreover, the production of such armor from elaborately small plates gradually came to naught with the beginning of internecine wars.

Interestingly, horse armor in Japan appeared in the Edo era and was intended only for parades and ceremonial rides. In the Edo era, ceremonial armor covered with chasing and engraving also became widespread.

In India, ceremonial armor was made from special small chain mail, the ends of the rings in which were bent, but not riveted or welded, which would cause the rings of such chain mail to crumble at the first blow.

In the East (Central Asia and the Middle East), it was common to wear over-armor clothing (robes and sometimes headdresses) over armor, which, in addition to protection from the sun, also performed ceremonial functions. At the same time, mirrors were worn over clothes.

In Medieval Europe, until the 15th century, combat armor was used as ceremonial armor, additionally decorated with heraldry: helmet figures (made of papier-mâché, parchment, fabric, leather, wood), shoulder shields, and coats of arms on a surcoat, mantle, horse blanket and brigantine. Some wore a real crown over a helmet or chainmail hood. In addition, the chain mail was decorated with woven copper rings, polished to a golden shine. Helmets were sometimes painted with a solution of gold in mercury, after the evaporation of which a golden design remained on the helmet. Additionally, a richly decorated knight's belt made of gold or gilded plaques (actually a sword belt in the form of a wide belt) was worn, and in the 14th century chains appeared (for hanging weapons and helmets), which could also be decorated.

In the 15th century, due to the widespread spread of armor, separately manufactured ceremonial armor based on combat armor appeared, differing from them primarily in that it was painted with gold. At the same time, in Germany, expensive armor, even if it was not ceremonial, had abundant corrugation, and plate shoes were equipped with extravagantly long toes that could be detached. And in Italy, richly decorated ceremonial helmets with an open face were in circulation.

In the 15th-16th centuries, some ceremonial armor was covered with elegant fabric decorated with heraldry and nailed to the metal with figured rivets. Moreover, some of these armors had a metal base hidden under the fabric that was heavily perforated to lighten the weight, so that such lightweight armor was unsuitable for combat, although it could be used for tournament duels with maces. What is noteworthy is that metal cuirasses covered with fabric actually appeared at the end of the 14th century, being then a type of large-plate brigantines (coracins), transitional from brigantines to armor.

At the end of the 15th - beginning of the 16th centuries, as a result of the influence of the Renaissance, ceremonial armor in the ancient style appeared, created in imitation of Roman and ancient Greek armor. Moreover, the Italians, who loved armor in the Italic style. alia romana (that is, Roman), one did not have to travel far to see what kind of armor the Romans wore.

At the beginning of the 16th century there was a real peak in fashion for ceremonial armor in the form of clothing, called costume armor.

Some ceremonial armor of the 16th century, called grotesque armor, either had a visor in the form of a human face, or was even made in the form of animals and mythological creatures. In the same 16th century, some armor was painted with enamel, drawing real pictures on them in the style of contemporary Renaissance paintings. Naturally, when the armor was hit, the enamel could not withstand and crumbled, which is why this armor, although it could withstand the blow of a weapon, was intended for parade, and not for battle. At the same time, in addition to gold painting, armor covered with chasing and engraving, as well as applications of gold and silver plates, became widespread.

In the 16th-17th centuries in Poland and Lithuania (as well as among the Belarusian and Ukrainian gentry), in connection with the very fashionable theory of “Sarmatism” from the time of Jan Sobieski about the Sarmatian origin of the gentry (other peoples were considered the ancestors of slaves), armor made of karacena (strong riveted scales), stylized as the scaled armor of Sarmatian cataphracts. Moreover, even ceremonial helmets of such armor were often made from caracena. Like contemporary hussar armor, it usually protected only the body and arms, sometimes having leg guards, but full-length armor was also available. One of such full-length armor is kept in the Armory Chamber of the Moscow Kremlin, and another exactly the same, belonging to the Uniszowski family, is kept in Wawel Castle in Krakow.

Suit armor

Armor in the form of clothing, often in the form of Renaissance clothing (for example, Landsknecht clothing), but armor stylized after the robes of the ancient Greeks and Romans was also found.

Armor in the form of clothing, often in the form of Renaissance clothing (for example, Landsknecht clothing), but armor stylized after the robes of the ancient Greeks and Romans was also found.

The peak of fashion for such armor occurred in the first quarter of the 16th century - the heyday of the Renaissance, the rise of landsknechts and cuirassiers and the beginning of the decline of knighthood. It was the last knights, inspired by the spirit of the Renaissance, who were the owners of such armor; It was precisely the insane high cost of such armor that led to the fact that many nobles, instead of being knighted according to tradition at the age of 21, preferred to remain squires and serve not as knights, but as cuirassiers, gendarmes, reiters, hussars, etc. ., and even go as officers to the infantry, which just a hundred years ago was unthinkable for many nobles. Possession of such extremely expensive armor was a matter of prestige for a knight, because every knight, arriving at a tournament or other formal event, tried to impress those around him. And if in previous centuries - during the times of chain mail and brigantines - this cost an acceptable amount (to do this, they simply decorated the helmets with painted coat of arms figures made of papier-mâché, wood or parchment, and put an elegant surcoat over the armor, also covering the horse with an elegant blanket), then in the 16th century, trying to impress others was ruinous. Moreover, in earlier times, tournament armor was also used in battle, but in the 16th century, few people wore tournament armor into battle. There were also special armor sets in which additional parts were attached to ordinary armor, turning it into tournament armor, but such sets were also very expensive and looked worse than costume armor. However, not all suit armor was suitable for tournaments. So, very fashionable and prestigious armor, stylized as antiquity, for example in the Italian style. alia romana (a la Roman), due to insufficient protection they were unsuitable for tournaments, and despite the fact that such armor was much more expensive than combat armor. The owner of such armor, although he sported it at the tournament, still put on another armor for the duel. Not every tournament participant could afford to have, in addition to tournament armor, “antique” armor, suitable only for a parade. Other types of costume armor, for example in the “de fajas espesas” style, were also suitable for tournament battles, as they provided good protection, and therefore armor that looked like clothing from the 16th century was very popular. The price of such armor was determined not only by the abundance of gold decorations and quality, but also by the complexity of manufacturing: since clothing of that era often had elaborate elements (for example, huge puffy sleeves), not every blacksmith could forge such armor - so the most impressive armor was also the most expensive.

Armor for tournament fights. Could, but not necessarily, be ceremonial armor at the same time. Classic tournament armor (of the late 15th and entire 16th centuries), due to its too narrow specialization, was unsuitable for real combat. Thus, the classic armor for foot combat was not suitable for mounted combat, and the armor for spear fighting was not suitable not only for foot combat, but also for hacking on horseback. In addition to highly specialized armor, there were also armor sets, which were a real constructor made of plate parts. It could be used to assemble any tournament or battle armor, and even ceremonial armor.

Armor for tournament fights. Could, but not necessarily, be ceremonial armor at the same time. Classic tournament armor (of the late 15th and entire 16th centuries), due to its too narrow specialization, was unsuitable for real combat. Thus, the classic armor for foot combat was not suitable for mounted combat, and the armor for spear fighting was not suitable not only for foot combat, but also for hacking on horseback. In addition to highly specialized armor, there were also armor sets, which were a real constructor made of plate parts. It could be used to assemble any tournament or battle armor, and even ceremonial armor.

Since the emergence of tournaments, it was customary to use ordinary armor as tournament and ceremonial armor; the only difference was that additional chain mail was worn for the tournament, not counting the elegant cloak.

Mantels and surcoats, which appeared during the Crusades and were originally intended for protection from the sun, quickly gained popularity as a way to give armor an elegant look by decorating it with heraldry. The popularity of mantles and surcoats made horse blankets popular, also decorated with heraldry. Later, with the advent of the potted helmet, which had a comfortable flat or slightly convex platform on top, heraldic helmet figures made of papier-mâché, parchment, fabric, leather on a wooden frame began to be attached to this platform.

Over time, in the 12th-13th centuries, the surcoat, by attaching plates under it, turned into a brigantine (lentner), which was also decorated with heraldry. With the spread of the brigantine, the potted helmet, which by that time began to rest on the shoulders, during spear clashes on horses began to be fixed with chains, pulled to the brigantine in the position of the chin pressed to the chest. This reduced the risk of breaking the neck if the spear failed to hit the head.

In the last third of the 13th century, shoulder shields appeared, worn more often in tournaments than in battle, intended not so much to protect the shoulders, but to decorate with heraldry. However, despite their flimsiness, they still provided some protection for the shoulders.

In the 14th century, with the spread of visors for bascinets, the potted helmet gradually ceased to be worn in battle, continuing to be worn in tournaments, and by the end of the 14th century it turned into a purely tournament helmet. With the spread of armor, the pot helmet turned into the so-called “Toad Head”, screwed to the cuirass. The appearance of the “Toad Head” led to the fact that if earlier, during a horse collision, they bowed their heads, pressing their chin to their chest, then in a toad head, screwed to the cuirass, they straightened up so that the spear did not even accidentally hit the visual slit. In a helmet not screwed to the cuirass, getting hit in the head with a spear at full gallop was fraught with the risk of breaking your neck.

The armor for equestrian combat was characterized by an extremely narrow specialization, which made it unsuitable for anything else. Often weighing twice as much as battle armor, it offered much less complete protection combined with minimal mobility and minimal visibility. It consisted of a thick cuirass to which the Toad's Head tournament helmet was screwed, which, in addition to reliable protection, had extremely poor visibility.

Since the armor weighed a lot, neither a plate gauntlet nor a plate glove was usually worn on the hand holding the spear, and protected by a huge shield of the spear, the size of a shield. Since the blow of the spear, according to the rules, was angled upward and forward, the legs could be hit either intentionally or in an accident. Therefore, in order to lighten the weight, the legs were either not protected at all, or their protection was limited to thigh guards, instead of which sometimes there were leg guards fastened to a cuirass or a plate skirt. However, if desired (for example, for a ceremonial exit), it was possible to wear full leg protection from other armor.

The spear hook on the cuirass was much more powerful than usual, and often, unlike usual, stuck out not only forward, but also back. Since active movements in the armor were not expected, the protection of the hand holding the reins was unique - instead of a plate gauntlet, an extension of the bracer with a U-shaped profile was used. The shields protecting the armpits were larger than usual, due to the lack of the need to actively move. The shield was initially simply attached as usual, then it began to be attached with cords to the cuirass supported by a special support. Later they began to screw it in place with screws.

Initially, it was distinguished by a very long plate skirt with a bell, for reliable protection of the genitals. But later, with the development of armor art, options appeared that provided reliable protection without a long plate skirt.

Initially, it was distinguished by a very long plate skirt with a bell, for reliable protection of the genitals. But later, with the development of armor art, options appeared that provided reliable protection without a long plate skirt.

Another characteristic feature was the shoulder-supported helmet, in which the impulse of the impact on the helmet was transferred not to the head, but to the shoulders to avoid concussions. Moreover, for fights with blunt weapons like a mace (i.e., when there is no danger that the tip of the weapon will accidentally hit the eye), instead of a visor, a large lattice made of thick rods was used, which gave a good view.

To protect the fingers, plate gauntlets were usually used, which could withstand blows to the fingers well. What is curious is that the helmet sitting on the shoulders, gauntlets and a long plate skirt made this armor similar in general outline to a cast-in-breast.

(English Greenwich Armour) - armor of the 16th century, produced in Greenwich in England, brought there by German gunsmiths.

(English Greenwich Armour) - armor of the 16th century, produced in Greenwich in England, brought there by German gunsmiths.

Greenwich workshops were founded by Henry VIII in 1525, and had their full name in English. “The Royal “Almain” Armories” (literally “Royal “German” Arsenals”, French Almain - the French name for Germany). Since the workshops were created for the production of “German” armor, the production was headed by German gunsmiths. The first Englishman to head the production was William Pickering in 1607.

Although the armor was supposed, according to Henry VIII, to reproduce the German ones, they nevertheless carried both German and Italian features, and therefore the Greenwich Armor, although made by German craftsmen (with the participation of English apprentices), are distinguished by researchers into a separate “English” style.

The pattern of borrowings from various styles in Greenwich Armor is as follows:

The cuirass (including both shape and design) is in the Italian style.

The helmet (before about 1610) is in the German style with a “Burgundian” gorge.

Hip guards and legguards are in the South German and Nuremberg style.

Shoulder protection - Italian style.

The execution of other details is in the Augsburg style.

It is important to mention that experts note the difference between the Nuremberg and Augsburg styles of German armor.

Incomplete armor worn by Landsknechts, the configuration and price of the armor depended on the rank and salary of the Landsknecht. A typical landsknecht's armor consisted of a cuirass with a necklace and legguards, which provided the only protection for the legs. Plate bracers of a simplified design were often part of the armor. Attached to the necklace were shoulder pads that reached to the elbow. The landsknecht's head was protected by a burgignot helmet; a little later (in the middle of the 16th century) the morion appeared. Shooters often used a special cassette helmet. By the 17th century armor in the form of simplified cuirasses and helmets was used only by pikemen.

Incomplete armor worn by Landsknechts, the configuration and price of the armor depended on the rank and salary of the Landsknecht. A typical landsknecht's armor consisted of a cuirass with a necklace and legguards, which provided the only protection for the legs. Plate bracers of a simplified design were often part of the armor. Attached to the necklace were shoulder pads that reached to the elbow. The landsknecht's head was protected by a burgignot helmet; a little later (in the middle of the 16th century) the morion appeared. Shooters often used a special cassette helmet. By the 17th century armor in the form of simplified cuirasses and helmets was used only by pikemen.

Armor worn both by Landsknechts on double pay and by poor cuirassiers.

It had the same design as cheap cuirassier and expensive Landsknecht armor. In the 16th century there was no longer a special design of armor “for landsnechts”, “for cuirassiers”, “for reiters” and so on. There was only full knightly armor, worn at that time only by the highest aristocracy and the gendarmes of the French king, and incomplete armor, worn by everyone else, including the reitar. Armor and weapons were purchased at their own expense, and therefore the difference between Landsknecht and cuirassier armor stemmed from who could afford what kind of armor. The usual landsknecht was often limited to an open helmet, a cuirass with shoulder pads and leg guards. A cuirassier, as a rule, a nobleman, could buy himself a closed helmet with a visor (armé or heavy burgignot), a cuirass, full hand protection, long legguards with knee pads and a pair of strong good boots, reinforced with steel plates - which was the difference between typical Landsknecht or Reitar armor. The similarity between Landsknecht and cuirassier armor appeared if the nobleman was impoverished, and the Landsknecht received a “double” salary. Reitar, in this regard, was much better off than an infantryman, but since his main weapon - wheeled pistols - were very expensive (for comparison: in the infantry only officers could afford pistols), he had to save on armor, since, unlike cuirassiers , for a reiter it was preferable to have good, expensive pistols and inexpensive armor than vice versa.

It had the same design as cheap cuirassier and expensive Landsknecht armor. In the 16th century there was no longer a special design of armor “for landsnechts”, “for cuirassiers”, “for reiters” and so on. There was only full knightly armor, worn at that time only by the highest aristocracy and the gendarmes of the French king, and incomplete armor, worn by everyone else, including the reitar. Armor and weapons were purchased at their own expense, and therefore the difference between Landsknecht and cuirassier armor stemmed from who could afford what kind of armor. The usual landsknecht was often limited to an open helmet, a cuirass with shoulder pads and leg guards. A cuirassier, as a rule, a nobleman, could buy himself a closed helmet with a visor (armé or heavy burgignot), a cuirass, full hand protection, long legguards with knee pads and a pair of strong good boots, reinforced with steel plates - which was the difference between typical Landsknecht or Reitar armor. The similarity between Landsknecht and cuirassier armor appeared if the nobleman was impoverished, and the Landsknecht received a “double” salary. Reitar, in this regard, was much better off than an infantryman, but since his main weapon - wheeled pistols - were very expensive (for comparison: in the infantry only officers could afford pistols), he had to save on armor, since, unlike cuirassiers , for a reiter it was preferable to have good, expensive pistols and inexpensive armor than vice versa.

Typical Reitar armor consisted of a cuirass with segmented legguards (usually knee-length), plate arm protection, a plate necklace and a helmet. Plate hand protection, depending on the wallet, could be complete, or it could be limited to segmented shoulder pads up to the elbows and plate gloves, also up to the elbows. The compromise version consisted of the same elbow-length shoulder pads and plate gloves, complemented by elbow pads. In addition to elbow pads, there could also be knee pads, which, if available, were usually attached to the thigh pads. As for the helmet, at first the burgignot with a visor and cheek pads, called the “assault helmet” (German: Sturmhaube), was popular. Usually the face was open, but if desired, if funds allowed, one could buy an option with a folding chin guard that covered the face like a visor, but not from top to bottom, but from bottom to top. The purely cuirassier version of the helmet - arme - did not enjoy noticeable popularity among the Reitar. Subsequently (German: Sturmhaube) gave way to the reiters, as well as arquebusiers, to the morion, and then to the shishak (kapelina), as it was more convenient for shooting. Since the reitar sat in the saddle and, as a rule, did not dismount in battle, the groin was well covered by the saddle and the horse, which made the codpiece practically unnecessary. Although, if there was a strong desire to wear it for ceremonial purposes, and the codpiece was often given a grotesquely large shape in order to emphasize the masculinity of its owner, it could be purchased additionally.

As for the black color of the armor, this color was found not only among the “Black Horsemen” and, in addition to aesthetic and psychological reasons, there were also practical reasons. On the one hand, an ordinary mercenary, not having a personal servant, monitored the condition of the armor himself, and therefore armor painted with oil paint was preferable to unpainted armor, since it was less susceptible to rust, and on the other hand, the blacksmiths who made the armor often used the paint themselves so that hide existing defects in cheap armor. As a rule, expensive armor was polished, and if it was necessary to give it a black color, it was not painted, but blued, which even better protected the armor from the effects of rust.

Cheap armor usually weighed about 12 kg, while expensive bulletproof armor was gray. The 16th century could weigh 30-35 kg, for comparison: the armor of the beginning of the 16th century weighed about 20-25 kg and covered the entire body.

The armor of a winged hussar, consisting of a segmented cuirass with long shoulder pads and wings attached to the back, bracers, and a shishak-type helmet (kapalin). Used mainly in the 17th century.

The armor of a winged hussar, consisting of a segmented cuirass with long shoulder pads and wings attached to the back, bracers, and a shishak-type helmet (kapalin). Used mainly in the 17th century.

The early hussars of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth of the early 16th century did not have metal armor, but wore only quilted caftans. Soon they had chain mail and chapels, borrowed from the Hungarians. Everything changed at the end of the 16th century - with Stefan Batory. This was cuirassier style cavalry. They often wore the skins of various animals over their armor, and also wore wings, which they wore on the side or back of the saddle, or even on the shield. But the armor itself, as a rule, was imported from Western Europe. The armor acquired its classic appearance only by the middle of the 17th century - during the reign of Vladislav IV. But firearms developed, and therefore hussars in metal armor lost their importance. In the 18th century, the hussars gradually turned into a ceremonial army. And finally, in 1776, the duties of the hussars were transferred to the lancers, along with which the armor was no longer used.

Before the reform of Stefan Batory, the cuirass was optional, and often instead of a cuirass a bakhterets, or even just chain mail, was worn, but the reform made the cuirass mandatory. Early varieties of hussar cuirass could be either solid (without segments) or completely consisting of many segments.

In the classic type of cuirass, the chest protection was not divided into separate segments for strength, while the lumbar protection was divided into several segments for flexibility. At the same time, the classic hussar cuirass is divided into Polish. typ starszy (“old type”) - from 1640 to 1675, and Polish. typ mlodszy (“new type”) - from 1675 to 1730. Both of these types differ not in design, but in the execution and finishing of parts noticeable only to a specialist (for example, in the “old” type the edges of the armor plates were bent inward, while in the “new” type they were left straight, etc., etc.). A more noticeable difference initially was that the “old” type had wings attached to the saddle, and not to the cuirass - like the “new” one. But this difference was leveled out back in the 17th century by attaching wing mounts to the “old” type of armor. And the fact that the mounts for the wings are not original, but newly made ones - again, only a specialist can notice.

The cuirass was forged with a thickness of 2 to 3.5 mm, and provided good protection against many types of bladed weapons. Weight was no more than 15 kg. The cuirass consisted of a backrest and a breastplate, a collar (necklace) and shoulder pads were connected to the cuirass with leather straps or steel loops. Bracers were worn to protect the forearms and elbows, so mobility was high. All elements of armor could often be decorated with copper or brass. The quality of finishing depended on the price of the armor. For example, armor bought according to the common practice in the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, by a rich hussar for a poor one, often had a crude finish that looked impressive only from a distance. While the armor of the master captain (who usually acted as one or another magnate) was distinguished by its subtlety and luxurious finish.

Classic hussar armor had bracers to protect the arms from wrist to elbow, and earlier, depending on the price, could be limited to chain mail sleeves, sometimes worn with plate gloves. As for the protection of the legs of poor nobles, whose armor (and often the war horse too) belonged to a comrade (and there were often more than two-thirds of such nobles in a hussar company, since a rich noble, becoming a hussar, was obliged to bring with him several warriors equipped at his own expense , and naturally, he did not bring slaves at all, but simply impoverished nobles), there was no separate protection for the legs. But those who owned the armor of the poorer hussars often had plate leg protection in the cuirassier style - from segmented leg guards ending in knee pads. In the early version, the upper part of the thighs could be covered with chain mail, both with chain mail worn under a cuirass, and with armor consisting of chain mail and a helmet, there could also be a chain mail hem worn with chain mail hands in addition to the cuirass.

During the time of Jan Sobieski, in connection with the very fashionable theory according to which the gentry descended not from the Slavs, but from the Sarmatians, armor in the “Sarmatian style” became popular among the rich gentry (with which, for greater “Sarmatism”, they wore... bows and arrows) , made from riveted scales and called karacena (Polish: Karacena). Such armor was very prestigious and cost so much that not every nobleman, who equipped two others with armor at his own expense, could afford such armor. Unlike hussar armor, whose leg protection (if any) was limited to legguards with knee pads, among the caracena armor there was full-length armor (with full leg protection). One of such full-length armor is kept in the Kremlin Armory, and another exactly the same, belonging to the Uniszowski family, is kept in Wawel Castle.

Initially, in the 16th century, the wing was a trapezoidal shield, which at first was simply painted by drawing feathers on it, and then they began to decorate it with real feathers. During the reform of the hussars by Stefan Batory, shields were replaced by a cuirass by royal decree. But, nevertheless, the wing did not disappear, but turned into a wooden strip with feathers, held in the hand like a shield. It was these wings that were sketched by German artists during the “Stuttgart Carousel”, which took place in 1616 in honor of the christening of the son of Friedrich von Wüttemberg. At the same time, for reasons of practicality and convenience, by the end of the 16th century (that is, more than a decade and a half before the “carousel”), the wing began to be attached to the left side of the saddle, and soon a second wing appeared, attached to the right. And by 1635, both wings crawled behind the back, remaining attached to the saddle. During the years of the “bloody flood,” when, due to the protracted war, according to eyewitnesses, only every tenth hussar was dressed in armor, wings also became a rarity. After the end of the protracted war, when the economy began to recover, the hetman, and then the king, John III Sobieski, made every effort to dress all the hussars in armor again, at the same time a fashion arose to attach wings not to the saddle, but to the cuirass. However, the Lithuanian hussars (and Lithuania and Poland constituted one state, the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth) even then continued to attach their wings to the saddle, and not to the cuirass.

Feathers - eagle, falcon, crane or ostrich, or brass plates instead of feathers - were attached to a wooden frame or a metal tube from 110 to 170 cm long.

According to different theories of wings, the following functions are attributed:

Protection from the lasso, which was actively used by the Cossacks, Turks and Tatars.

Additional protection of the back against blows from cold weapons.

When riding, the wings made a sound that could frighten enemy horses.

In case of a fall from the saddle, the impact on the ground was absorbed.

These wings were attached to the back of the cuirass on brackets, or were held on belts and, if necessary, were quickly unfastened. But they still had several drawbacks. This is, first of all, aerodynamic resistance and additional mass, which complicates the movement of the rider. It was also impossible to carry anything on your back. In addition, there were options not with two, but with one wing. This significantly reduced efficiency and looked worse, but it reduced weight and cost. The wings could also be attached not to the back, but to the saddle. This significantly increased the mobility of the rider, in which case they did not have to be removed. But at the same time, they could no longer protect themselves when falling from a horse. In addition, the wings could be not only of natural color, but also painted in different colors. The most widespread use of wings was among the Poles. Along with them, the wings were also used by some Serbian, Hungarian and Turkish cavalrymen.

Shishak, or kapelina (Polish kapalin), is a hemispherical helmet with a visor, ears, backplate and enlarged nosepiece, in some versions similar in size to a mask or half-mask. It was made from two welded plates, to which a visor was riveted, a segmented backplate was attached, the ears were held on leather straps, and the nosepiece passed through the crown and was movable. This type of helmet came to Poland from Hungary, as a modification of the Russian erikhonka, which in turn arose on the basis of eastern shishaks. The top of the Polish helmet was decorated with either a spire or a high crest, which had a protective function. Then from Poland this type of helmet came to Europe, spread in France as “Capeline”, in Germany as “Pappenheimer” (German: Pappenheimer-Helm), and, later, other popular helmets were developed on its basis. But many of them still retained the transliterated name “shishak”. Therefore, the hussars wore not only Polish-made helmets, but also captured ones, including German and Turkish ones.

The worlds of D&D are a wide tapestry woven from diverse cultures, each at a different level of technology. Therefore, adventurers can come across a wide variety of armor, from leather jackets and chain mail to expensive armor. The "Armor" table below lists the characteristics of the most common armor, divided into three categories: light, medium and heavy. Many warriors add a shield to their armor.

The Armor table shows the cost, weight, and other properties of the most common armor in D&D worlds.

Mastery of armor. Anyone can don armor or strap a shield to their arm. But only those who know how to wear armor can wear it effectively. Your class grants proficiency in certain types of armor. If you wear armor that you do not wield, you have disadvantage on all ability checks, saving throws, and attack rolls that use Strength or Dexterity, and you cannot cast spells.

Armor Class (AC). The armor protects the wearer from attacks. The armor (and shield) equipped determines the base Armor Class.

Heavy armor. Heavier armor makes it difficult for the wearer to move freely and quietly. If the armor column says "Str 13" or "Str 15", the armor reduces the wearer's speed by 10 feet if the wearer's Strength is less than that value.

Stealth. If the armor column says “Handle,” the wearer has disadvantage on Dexterity (Stealth) checks.

Shields. The shield is made of wood or metal and is carried with one hand. Using a shield increases AC by 2. You only benefit from one shield at a time.

| Armor | Price | Armor class (AC) | Strength | Stealth | Weight |

| Light armor | |||||

| Quilted | 5 gp. | 11 + DOC modifier | - | Interference | 8 lb. |

| Leather | 10 gp. | 11 + DOC modifier | - | - | 10 lb. |

| Studded leather | 45 gp. | 12 + DOC modifier | - | - | 13 lb. |

| Medium armor | |||||

| Shkurny | 10 gp. | 12 + VOC modifier (max 2) | - | - | 12 lb. |

| Mail shirt | 50 gp. | 13 + VOC modifier (max 2) | - | - | 20 lb. |

| Scaly | 50 gp. | - | Interference | 45 lb. | |

| Cuirass | 400 gp. | 14 + VOC modifier (max 2) | - | - | 20 lb. |

| Half armor | 750 gp. | 15 + DOC modifier (max 2) | - | Interference | 40 lb. |

| Heavy armor | |||||

| Kolechny | 30 gp. | 14 | - | Interference | 40 lb. |

| Chainmail | 75 gp. | 16 | 13 | Interference | £55 |

| typesetting | 200 gp. | 17 | 15 | Interference | 60 lb. |

| Armor | 1,500 gp. | 18 | 15 | Interference | 65 lb. |

| Shields | |||||

| Shield | 10 gp. | +2 | - | 6 lb. | |

LIGHT ARMOR

Light armor, made from lightweight, thin materials, is favored by agile adventurers as it provides protection without restricting mobility. If you wear light armor, you add your Dexterity modifier to the base number provided by the armor when determining your Armor Class.

Quilted. Quilted armor consists of stitched layers of fabric and batting.

Leather. The breastplate and shoulders of this armor are made of leather boiled in oil. The remaining parts of the armor are made of softer and more flexible materials.

Studded leather. Made from tough but flexible leather, studded armor is reinforced with closely spaced spikes or rivets.

MEDIUM ARMOR

Medium armor offers better protection than light armor, but slightly restricts movement. If you wear medium armor, you add your Dexterity modifier, up to a maximum of +2, to the base number provided by the armor when determining your Armor Class.

Selfish. This crude armor is made of thick furs and hides. They are usually worn by barbarian tribes, evil humanoids and other peoples who do not have the tools and materials to create better armor.

Chain shirt. Made from interlocking metal rings, a chain mail shirt is worn between layers of clothing or leather. This armor provides moderate protection to the torso and muffles the ringing of rings with an outer covering.

Scale armor. This armor consists of a leather jacket and leggings (and possibly a separate skirt) covered in overlapping pieces of metal that resemble fish scales. The set includes mittens.

Cuirass. This armor consists of a fitted metal shell worn lined with leather. Despite the fact that the arms and legs are left with virtually no protection, this armor protects vital organs well, leaving the wearer with relative mobility.

Half armor. Half armor consists of molded metal plates that cover most of the wearer's body. They do not include leg protection other than simple greaves secured with leather straps.

HEAVY ARMOR

Of all types of armor, heavy armor provides the best protection. These sets of armor cover the entire body and are designed to protect against a wide variety of attacks. Only the most trained warriors can withstand their weight and load.

Heavy armor does not allow you to add a Dexterity modifier to your Armor Class, but it also does not give a penalty if your Dexterity modifier is negative.

Ring armor. This is leather armor with thick rings sewn onto it. These rings strengthen your armor against blows from swords and axes. Ring armor is inferior to chainmail and is usually worn only by those who cannot afford better armor.

Chain mail. Made from interlocking metal rings, chainmail also includes a layer of quilted fabric underneath to prevent chafing and cushion blows. The set includes mittens.

Set armor. This armor consists of narrow vertical metal plates riveted to a leather backing worn over a layer of batting. The connections are protected by chain mail.

Armor. Plate consists of formed metal plates that cover the entire body. The armor set includes gauntlets, heavy leather boots, a helmet with a visor, and a thick layer of batting. Straps and buckles distribute weight throughout the body.

PUTTING ON AND REMOVING ARMOR

The time required to put on and take off armor depends on its type.

Putting on. This is how long it takes to put on armor. You only get AC from the armor if you spent the required time putting it on.

Removal. That's how long it takes to remove the armor. If you have help, cut the time in half.

EQUIPMENT FIT

In most campaigns, you can carry and use any equipment you find within the bounds of common sense. For example, a bulky half-orc will not be able to squeeze into the leather armor of a halfling, and a gnome will get tangled in the robes of a cloud giant.

The master can enhance this realism. For example, armor made for one person may not fit another without significant modification, and a guard's uniform may look noticeably alien if an adventurer wears it for camouflage.

These additional rules require that when adventurers find armor, clothing, or other similar items that are meant to be worn, they must visit an armor maker, tailor, tanner, or other specialist who will have the item tailored for them. The cost of this work ranges from 10 to 40 percent of the market value of the item. The GM can determine the cost using the 1d4 x 10 method, or decide what price to charge based on the total.

- Material taken from the pdf version of the translation "Player's handbook" from the studio "

Good afternoon dear Assembly.

Not long ago, I made a fascinating trip to sunny Europe, where I visited a number of museums and castles; having managed to work with native Renaissance artifacts.

However, the main event of my trip was visiting the world's largest exhibition of defense and weapons Hofjagd- und Rüstkammer(National Library), located in the city of Vienna in Austria.

Having already been there in November 2012 and collected a lot of photographic material, I went there again.

The cards worked out in such a way that I was able to meet very good and important people in Europe, who led me to the director of the museum, Herr Matthias Pfafenbichler.

That day the museum was closed to tourists, but they let me in and allowed me to study the armor of Georg von Frundsberg in detail.

I was taken to their restoration workshop and given white rubber gloves and the necessary tools.

The museum staff removed George's armor from the mannequin and tapped me on the shoulder and said go ahead!

GETTING STARTED

I spent more than four hours studying the artifacts in detail. The objects of my research were the following parameters: dimensions, geometry, weight and thickness of the armor of Georg Von Frundsberg and the Arme helmet of Patricius Tucher.

The question of the thickness of the bibs of the early 16th century in the field of modern reconstruction has always remained a mystery to many. No matter the specialists I talked to, many of them agreed on 1.5mm about the thickness issue. An analogue of what modern armor makers now make. The figure of 1.5 mm was taken, probably, based on the thickness of the rolled steel sheet. Well, let's turn to the artifacts for the truth.

What is Georg's armor like at the moment?

1) cuirass with back and skirt

2) tasetas.

the rest, according to Matthias, was lost over the years.

During the research, I had the following tools: many rulers; roulette; centimeter; calipers, protractors and thickness gauges, unfortunately, with a small radius of measuring “whiskers”.

Below I provide diagrams. All dimensions are indicated in millimeters. I drew the geometry on the diagram as close as possible to the original.

BIB

The breastplate has two round holes: one almost in the center, the other in the center at the top. The diameter of both is approximately 5 mm.

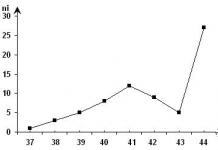

Gray dots indicate approximate locations for taking thickness measurements.

The measurement error, I think, is minimal.

Thickness.

I did not draw a diagram of the backrest, because it is the same thickness as the breastplate. Also from 4.5mm closer to the tops and a smooth decrease in thickness towards the edges to 0.8-0.9mm.

By the way, when wearing a cuirass, I think everyone knows about the overlap of the sides of the breastplate and the backrest. Therefore, the total thickness in this zone will be 0.9 + 0.9 = 1.8 mm.

MOVING PLATES

their thickness turned out to be small: from 0.9 (top and bottom) - 1.2 (center) mm.

extend beyond the bib by 30.5mm.

rolling width 16 mm. in the center.

The total width of the plates is 47 mm.

SKIRT

Weight of cuirass, breastplate and skirt.

The total weight of the assembled cuirass turned out to be about 12 kg.

The tassets turned out to be very light due to the small thickness of the plates.

TACETS

the cases turned out to be “paper”(((

so, for example, in the center 0.9-1.2 and at the edges from 0.5 to 0.7.5 mm.

GENERAL IMPRESSION

Comparing the horizontal and vertical dimensions of the bib, you can see that, for example, one side of the bib is shorter than the other, almost two centimeters. The moving plates are also of different sizes. The skirt plates are different from each other.

If the width of the bottom plate of the skirt at the edge on the left is 61mm, then on the right it is 52mm.!!! This is a 9mm difference. That is actually 20%!!!

The plates are not the same width and length. And the total length of the two belts is 4 cm different!!!.. This can be attributed to the restorers who used belts of this length. But they are still crooked.

The main conclusion.

Having studied the armor of Georg von Frundsberg, I finally dissuaded myself of any standardization of the exact armor structure, that all the dimensions of the elements were measured with great accuracy. This is wrong! To put it mildly, they were measured by eye. That is, visually, approximately exactly, if you don’t look closely, it means the piece of hardware is good and can be worn. The main thing is to protect it and not rub it too hard.

Moreover, George’s armor is not the armor of an ordinary soldier, who would have been given the same treatment. Frundsberg was a wealthy military commander and nobleman who was able to pay for the services of quality craftsmen. Therefore, they did it well and beautifully for him. By the way, the rich etching classifies its iron as a higher caste of armor. And if you don’t look closely, George’s armor is beautiful. However, having measured it, it is crooked.

As for the armor for ordinary soldiers, for example, for comparison, the skirt of an infantry cuirass from 1500 on an ordinary soldier (bollard).

It’s also all crooked and embarrassing to wear. Our squeamish reenactor wouldn’t wear one)))

Thickness

Cuirasses of the early 16th century were quite thick. Holding Georg's cuirass in my hands, I realized that it was impossible to penetrate it with anything.

Even firearms of that period, for the most part, would hardly have penetrated 4.5 mm of hardened steel. Not to mention melee melee weapons.

This fact, by the way, once again confirms our theory about the ineffectiveness of “sports” spitting at Soviet fencing tournaments. No matter how you “spit” small and quick blows at this cuirass, there will not be a scratch.

By the way, about scratches! They weren't on the armor! Except for one thing: on the backrest, on the left, there is a barely noticeable dent, no more than 0.5 mm deep, as it seemed to me. And the thickness of the “armor plate” in that place was about 4mm.

Someone nevertheless caught Georg in the battle in the area of the kidneys, but this did not cause any harm to his health or armor.

In addition to a detailed study of the armor of Georg von Frundsburg in the Vienna National Library, I was able to study (though without changing instruments) by eye the Maximillian cuirass of 1515. Exhibited in the Neuburg Castle Museum. It hung outside the display case and Kostya and I were able to touch it.

short video about max.cuirass

So here it is. The thickness, by eye, seemed to be about 2.5-3mm at the top of the cuirass and 3mm in the center, gradually tapering down to about 1.5mm towards the sides.

Other artifactsAlso, in the restoration workshop I held in my hands the famous Negrolli helmet; parts of Kaiser Max's tournament armor set and a hand from costume armor (guess who?), etc.

Also, at my request, Matthias removed the helmet of the army of Patricius Tucher and I studied it in detail.

Preempting the article about the geometry of arme, I will immediately state that in the USSR there is not a single correctly made arme at the moment. Even my combat helmet has some errors in the geometry of the back of the head, for example.

RESULT

We gained, albeit initial, but still gigantic experience in the basics of armor science in Europe in the 16th century. Based on this, one can make assumptions about armor-building technologies.Now, our Frundsberg Army can proudly say that it cooperates with leading European museums and medievalists. After looking at the photographs of the Army, exhibition director Matthias Pfafenbichler highly appreciated our success in reconstructing the Landsknechts of the early 16th century and praised our armor, made in our Tula workshop.

I couldn’t resist Georg’s cuirass and tried it on myself. In terms of height, I was just right, but in terms of width, I turned out to be thinner in the shoulders than the famous Landsknecht leader.

Cuirass(French “cuirasse”, Latin “coriaceus”, “made of leather, of corium”, since in the original the breastplate was made of leather) - plate armor, structurally representing a single piece of metal or other hard material, or consisting of two or more parts that protect the wearer's chest. In full armor, however, since this important piece was usually worn along with a corresponding back protector, the term "cuirass" usually meant a complete torso protection package, including both chest and back plates. Thus this full armor in the Middle Ages was often described as a pair of plates. Corslet (French "corselet", a diminutive form of the French word for "body"), a relatively light cuirass, is strictly speaking only a breastplate. For example, Elizabeth I of England often wore a cuirass.

As part of the military equipment of classical antiquity, cuirasses and corslets were made of bronze, and in later periods also of iron or some other hard material commonly used. Although some additional chest protection had been worn by warriors in earlier times, in addition to chain mail hauberks and clothing reinforced with plates and rivets, it was not until the 14th century that plate torso protection could be said to have become a standard component of medieval armour. .

Over the course of the 14th century, the cuirass gradually began to be used everywhere, together with plate protection of the limbs, and by the end of the century it was practically not found in the armor of knights, with the exception of the chain mail pendant of the bascinet and on the edges of the hauberk.

Cuirass, worn in the 14th century, was always made of just enough length to rest on the hips; otherwise, if it were not thus supported, it would have to be supported on the shoulders, which would interfere with the free and energetic movements of the owner.

At the beginning of the 15th century, all plate armor, including the cuirass, began to be worn without a surcoat; but in the last quarter of a century a short, short-sleeved surcoat, known as a tabard, has come into common use in armour. At the same time, when the disuse of the surcoat became general, small plates of various shapes and sizes (and not always made symmetrically: plates for the right hand, i.e. the one in which the sword was held, were often smaller and lighter than the pair them on the other side) were attached to the armor in front of the shoulders to protect the most vulnerable points, where the plate protection of the upper arms and cuirass formed a gap on each side.

Around the middle of the century, instead of being formed from a single plate, the breastplate of the cuirass began to be made in two parts, with the lower part being overlapped with the upper by means of straps or movable rivets, which gave flexibility to the armor. In the second half of the 15th century, the cuirass was sometimes replaced by the brigandine, an armor formed from textile fabric, mostly expensive material, lined with metal scales that were attached to the fabric with rivets, with the heads visible from the outside.

In the 16th century, sometimes high-ranking persons wore luxurious surcoats over their armor. During the first half of the century, the chest part of the cuirass, spherical in shape, was constantly strengthened with additional plates attached to it with rivets or screws.

Around 1550, the chest portion of the cuirass had a vertical central ridge, called a "tapul", which had a projecting apex near the middle; this apex was later moved lower, and eventually the apex was moved to the base of the cuirass, which led to the appearance of a distinctive form of cuirass - the "peascod" cuirass.

Corslets, having a chest and a back section, were worn by infantrymen in the 17th century, while horsemen were equipped with heavier and more durable cuirasses; these armors continued to be used after other pieces of armor were gradually discarded one by one. Their use, however, never completely ceased, and in modern armies the mounted cuirassiers, protected as in early times by chest and back plates, imitated to some extent the glorious brilliance of the armor of the era of medieval chivalry. Both French and German heavy cavalry were equipped with cuirasses until World War I.

A few years after Waterloo, some historical cuirasses were taken from the Tower of London, and fitted for service by the Life Guards and Horse Guards. For ceremonial purposes, the Prussian Garde du Corps and other corps wear cuirasses made of richly decorated leather.

Japanese cuirass

Breastplates have been made in Japan since the 4th century. Tanko, worn by foot soldiers, and keiko, worn by horsemen, were pre-samurai types of early Japanese cuirass, made of iron plates connected to each other by leather straps. During the Heian period (794-1185), Japanese cuirasses developed into a more recognizable style worn by samurai, known as "dou" or "do". Japanese craftsmen began to use leather and varnish to protect elements of armor from the effects of precipitation. Towards the end of the Heiyan period they took on a form clearly associated with samurai. For the manufacture of cuirasses, leather and iron scales were used, connected by leather (sometimes silk) cords. The advent of firearms in Japan in 1543 led to the emergence of a new type of cuirass - steel plates completely replaced leather plates as bullets completely replaced arrows and spears. Breastplates were used in Japan until the 1860s, when the end of the samurai era and the emergence of a national army using traditional uniforms ended the use of armor in that country.

Breastplates have been made in Japan since the 4th century. Tanko, worn by foot soldiers, and keiko, worn by horsemen, were pre-samurai types of early Japanese cuirass, made of iron plates connected to each other by leather straps. During the Heian period (794-1185), Japanese cuirasses developed into a more recognizable style worn by samurai, known as "dou" or "do". Japanese craftsmen began to use leather and varnish to protect elements of armor from the effects of precipitation. Towards the end of the Heiyan period they took on a form clearly associated with samurai. For the manufacture of cuirasses, leather and iron scales were used, connected by leather (sometimes silk) cords. The advent of firearms in Japan in 1543 led to the emergence of a new type of cuirass - steel plates completely replaced leather plates as bullets completely replaced arrows and spears. Breastplates were used in Japan until the 1860s, when the end of the samurai era and the emergence of a national army using traditional uniforms ended the use of armor in that country.

Thorax or Muscular Cuirass (decorated stylization).

St3, thickness 1.5mm, Polished.

Lorica Musculata is an anatomically shaped Dverne-Roman shell that is derived from the ancient Greek thorax. The very first Roman armor looked like two plates (chest and back) held on over-the-shoulder straps, a kind of sword belt.

And only over time, after several contacts between Roman and Greek civilization, Lorica Musculata appeared. This armor completely replaced the first armor of the Roman legionnaires of the early republic, and was used as standard armor until the end of the 2nd and beginning of the 1st centuries. BC Lorica Musculata showed itself all this time as a reliable and practical armor that did not greatly restrict movement, but a more interesting option appeared that gave greater freedom of movement, while not being much inferior in protective qualities. Lorica Hamata was more expensive to produce than the Muscle Carapace, but it lasted longer and was cheaper to repair, which is why Lorica Hamata became the standard protection. Lorica Musculata remained as the armor of senior officers, in contrast to Lorica Plumata, which was used by middle-ranking officers. During the Roman Empire, only generals, legates and the emperor himself could wear armor.

The first types of Roman thorax for soldiers of the republic were made of bronze and consisted of two parts (chest and back), which were fastened together using belts. They differed in length from the imperial versions only in that they covered the warriors' torso only up to the hips. Imperial officer's armor was very different because it was made not only from bronze (which became one of the rarest options at the time), but also from leather and iron (later versions began to be created from steel). Also, leather strips, often with sewn metal plates, began to be attached to the lower part of the armor in a vertical position, which made the armor approximately knee-length and in this case the protection extended not only to the torso, but also to the upper legs. Among other things, some of Lorik Musculat's armor was made not only consisting of 2 parts, but also monolithic (of course, with the exception of leather strips). In any case, after being removed from service, the Lorica Musculata became more of a ceremonial armor than a combat one.