From the editors of Skepticism: In Soviet history textbooks and in those post-Soviet ones where due attention was paid to populism, Pyotr Lavrov was presented as a leader or one of the leaders of the propaganda trend, opposed to Bakunin and Tkachev, the radical leaders of the anarchist and Blanquist trends, opponents of each other and Lavrism. Tkachev was mistaken in his conspiratorialism and isolation from the people, Bakunin in his adventurism and rebellion, and Lavrov in his moderation; This was the official Soviet scheme, which still determines the views of many leftists and not only leftists on the populist stage. As the published biographical sketch shows, Lavrov’s activities do not easily fit into this scheme. Initially close to the liberal populists, from the mid-1860s he was always a strong supporter of social revolution, and in 1871 he supported the Paris Commune. He did not find a common language with those who created the second “Land and Freedom”, combining propaganda with struggle (he was a member of the first and learned the most important lesson from its experience: it is a mistake to expect that the people themselves will rise to revolution) - but already in During the existence of “Narodnaya Volya”, he reevaluated his views, saw the importance of Narodnaya Volya for the development of the revolutionary movement in Russia and helped the Executive Committee of the organization.

Lavrov, who inspired a huge number of commoners to carry out propaganda work, was often criticized (including by those who initially followed him) for the preference he gave to propaganda over action. But, firstly - and this is mentioned in the essay - Lavrov did not actually adhere to this preference, recognizing that where propaganda is impossible or exhausts itself, direct action becomes a necessity - it was thanks to this conviction that he came to cooperate with the Narodnaya Volya . Secondly, his theory of propaganda turned out to be relevant even when the populist stage had long ended: thus, of course, the idea expressed by Lenin at the beginning of the 20th century that the working class is not able to get out of a purely economic struggle on its own is based on socialist political consciousness can only be given to him from the outside, there are similar arguments by Lavrov about his historical situation, although it is impossible to recognize Lenin’s idea as just a copy of Lavrov’s, Mikhail Sedov correctly emphasizes. This theory turns out to be relevant even today, during the period of complete destruction of the social sphere and accessible education, during the period of zombification by mass culture, when the demoralization of the population and the decline in its intellectual level are accelerating. In our situation, education, propaganda and counter-propaganda are of particular importance, and one of the main current tasks is to give them the greatest possible scale. Therefore, Lavrov's legacy - along with that of other revolutionary thinkers of that period - requires careful study, and this short biography serves as an excellent introduction to the views of one of the most important theorists of populism.

If you ask the question, what was the main thing in the revolutionary activity and literary work of P.L. Lavrov, there can be only one answer: the desire to awaken the Russian people to a conscious life, to raise them to the recognition of the need for revolution and a decisive restructuring of existing conditions. The next words from P.L. Lavrov can be an epigraph to his biography:

“One people has... enough energy, enough freshness to carry out a revolution that would improve the position of Russia. But the people do not know their strength, do not know the ability to overthrow their economic and political enemies. We need to raise it. The living element of the Russian intelligentsia has the responsibility to awaken it, to raise it, to unite its forces, to lead it into battle. He will destroy the monarchy that oppresses him, crush his exploiters and develop with his fresh forces a new, better society. Here and only here is the salvation of Russia.”

Highlight the role of P.L. Lavrov in the revolutionary movement of Russia is a complex and responsible matter. P.L. Lavrov was constantly in the center revolutionary events; his name and teachings caused lively controversy (especially interesting in this regard are the critical speeches against Lavrov by P.N. Tkachev and M.A. Bakunin). Meanwhile, we still do not have any complete collection of his works, not to mention a source analysis of them.

Historiography P.L. Lavrova originates from N.S. Rusanov, a famous publicist of the radical democratic school, a close friend and ally of Pyotr Lavrovich. By decision of the “Committee in Memory of P.L. Lavrov" (it included representatives of all factions of the Russian revolutionary movement, including the Social Democratic) N.S. Rusanov wrote an extensive and conscientiously executed article “P.L. Lavrov (essay on his life and work)". In this work, Lavrov appears before us in three qualities: as a person, as a social revolutionary, and as a thinker-theorist. According to N.S. Rusanov, Lavrov had “one of the most encyclopedic heads that ever existed in Russia (and, perhaps, abroad).” The author calls Lavrov “a hero of thought and conviction,” but rightly admits that he did not and could not become a follower of K. Marx and F. Engels, although he repeatedly called himself their student. Such a correct conclusion, unfortunately, was not accompanied by an indication that Lavrism as a system of views is strictly historical, that it could neither be a guide nor a banner of struggle for a new era of the revolutionary movement. The strength and significance of Lavrov and Lavrism are in the past, in the preparation of revolutionary protest and struggle of the masses, “in clearing the way,” as A.I. put it. Herzen. However, in Lavrov’s literary heritage there are provisions that are important not only in historically, but also have a completely modern sound. We will talk about this later, however. Subsequently N.S. Rusanov repeatedly turned to Lavrov’s work, but the main points he expressed in the above-mentioned article remained unchanged.

Before the revolution, special works about the role of P.L. Lavrov was not in the Russian revolutionary movement, although in general works his name occupied one of the first places. All this literature in its direction can be called bourgeois-liberal. She views Lavrism mainly as a socio-political utopia, a delusion, a “separation” from real life. Class analysis was alien to pre-revolutionary authors. They did not see Lavrov’s teachings as reflecting the interests of the peasantry. But already at that time there were researchers who saw in Lavrism something between Marxism and populism. A well-known expert on the history of Russian utopian socialism K.A. Pajitnov wrote that Lavrov “cannot be called either an orthodox populist or an orthodox Marxist; he was, so to speak, a populist in Marxism or a Marxist in populism.” The inconsistency of this view is obvious. Nevertheless, it received a well-known reflection even in Soviet literature.

Enormous opportunities for studying the revolutionary activities of P.L. Lavrov opened after October revolution. In the early 20s, the scientific community celebrated two anniversaries of P.L. Lavrov - the 20th anniversary of his death and the 100th anniversary of his birth, which undoubtedly increased interest in him. The literary reflection of the anniversary events were two collections of articles - “Forward” and “P.L. Lavrov", published in 1920–1922. Many of Lavrov’s works that were previously banned by censorship were republished. Thus, his books “The Paris Commune” (1919), “The Social Revolution and the Problems of Morality” (1924), “Populists Propagandists” (1925) were published. It was intended to publish Lavrov's collected works. Personality of P. L. Lavrov and his literary creativity attracted the attention of historians. Different points of view emerged on the problem as a whole and on its individual aspects. M.N. Pokrovsky argued that Lavrov was not a consistent revolutionary, and his views were eclectic and conservative. Opposite views were expressed by I.S. Knizhnik-Vetrov and B.I. Gorev, who tried to prove that there is much in common between Marxism and Lavrov’s teachings, that Lavrov’s tactical principles are close to the principles of the Third International. This was a clear modernization, but in those years this interpretation had some success. There were other opinions. So, D.N. Ovsyaniko-Kulikovsky argued, for example, that Lavrov is generally a random figure in the revolutionary movement.

The difference in points of view did not exclude, however, the general recognition of the fact that Lavrov as a person and Lavrism as a system of views occupied a significant place in the Russian liberation movement of the 19th century. The introductory articles of I.A. were devoted to the disclosure of this circumstance. Teodorovich and I.S. Knizhnik-Vetrova to the first volume of Lavrov’s selected works, published in 1934. Individual errors do not deprive these articles of interest. IN AND. Lenin, according to V.D. Bonch-Bruevich, among the materials of the revolutionary underground press recommended for republication, also named “Forward” published under the leadership of Lavrov. IN last years after a significant break Soviet historians returned to the study of the problems of populism. In particular, works have appeared that highlight certain aspects of Lavrov’s life and work. So, B.S. Itenberg examined in detail the question of the revolutionary influence of Lavrov’s “Historical Letters” on the youth of the 70s. Works of a philosophical and sociological nature related to the topic under consideration were published. From the above it is clear that, despite the contradictory concepts about P.L. Lavrov, his role in the revolutionary movement was significant and his literary heritage and practical activities require careful study.

Pyotr Lavrovich Lavrov was born in 1823 into the family of a wealthy and conservative nobleman in his views. His father, Lavr Stepanovich, was closely acquainted with the temporary worker Arakcheev and was even introduced to Emperor Alexander I. Thus, the social environment from which the future ideologist of populism emerged did not contain anything that would promote freethinking and radicalism. The young man grew up and was brought up in an atmosphere of extreme religiosity and exceptional devotion to the official foundations of Russian life. At the same time, from early childhood he was instilled with respect for work and an exceptional love of books - qualities that he carried throughout his life.

At the age of fourteen, Peter was assigned to the Artillery School and at the age of nineteen, having graduated brilliantly, he became an officer, revealing high talents and a passion for mathematics. In 1844 he was admitted to the same school as a teacher general course mathematics. Being in a military institution did not prevent P.L. Lavrov to show interest in social and political issues. He became thoroughly acquainted with the history of the French bourgeois revolution of the late 18th century, and its events fascinated him. At the same time, Lavrov read Fourier’s works for the first time. Some of the social ideas of the great French utopian thinker made a great impression on the young man. Quite early, Lavrov began writing poetry. Some of his poems were successful and passed from hand to hand in manuscript. However, he did not have a poetic talent, and N.A. Nekrasov, apparently, correctly characterized this side of Lavrov’s work, saying that his poems are rhymed editorials. Already at school, Lavrov created “his own” philosophy of history, which can be expressed like this: “What will happen, will not be avoided.” Lavrov himself called it philosophical fatalism. Soon, however, under the influence of the rapid developments of events inside and outside Russia, this view changed: Lavrov began to emphasize the active role of the individual, the party and the masses in historical events. By the 1930s, according to Lavrov, his worldview

“in general terms it was established, but for him it became clear and worked out in detail only in the process of literary work in the late 50s. Since then, he has found it neither necessary nor possible to change it in any significant point.”

During the period of preparation and implementation of the peasant reform, P.L. Lavrov actively declared himself in public life. He collaborated in publications by A.I. Herzen, stood close to the student movement and constantly provided assistance to its participants. Lavrov has always been at the center of events and literary movements of the progressive camp; he became part of the “Land and Freedom” of the 60s. Although his revolutionary sentiments had not yet taken shape, the government nevertheless considered him an unreliable person. That is why P.L. Lavrov was put on trial and exiled to the city of Kadnikov, Vologda province, in connection with the Karakozov case, although his involvement in it was not legally proven.

During the years of exile P.L. Lavrov wrote and published his “Historical Letters,” a work that was destined to play a truly outstanding role. Obviously, their intention, or at least their main ideas, must be attributed to more early period. “Historical Letters” were published in the magazine “Nedelya” (1868–1869), and in 1870 they were published as a separate publication. Even in the democratic camp they were regarded differently. A.I. Herzen put them very highly, N.K. Mikhailovsky, on the contrary, did not attach any importance to them, and P.N. Tkachev spoke out with sharp criticism. Young people immediately adopted them. It seems to us that the secret of the success of the “Historical Letters” was that they revealed a new view of the history of society and showed the possibility of turning a blind historical process into a conscious process, and man was considered not as a toy of unknowable laws, but as the center historical events. Pointing out to a person that his fate is in his own hands, that he is free to choose the path of development and achievement of the ideal, “which must inevitably establish itself in humanity as a single scientific truth,” in itself seemed to be an important and truly mobilizing means. This was the answer to the question of what to do. This is how the subjective method appeared in sociology, as the antithesis of bourgeois objectivism.

In theoretical terms (as has long been noted) P.L. Lavrov organically combined the idea of D.I. Pisarev about “thinking realists” with an appeal to N.A. Dobrolyubov’s message to young people is to “act on the people directly and directly” in order to prepare them for a conscious life. These elements formed Lavrov’s well-known formula for progress:

“The development of the individual in physical, mental and moral terms, the embodiment of truth and justice in social forms - this is short formula, embracing, it seems to me, everything that can be considered progress.”

Despite the abstractness, this formula clearly reveals the idea of the need for a decisive change in the existing foundations of social and state life, since under them the development of the individual is impossible, neither physically, nor mentally, nor morally.

Emphasizing that the general economic depression of the exploited sections of society, their cultural backwardness and downtroddenness, in fact, disfigure the personality in the physical and mental sense, P, L. Lavrov continued, emphasizing the moral side:

“The development of personality in moral terms is only possible when the social environment allows and encourages the development of independent conviction in individuals; when individuals have the opportunity to defend their various convictions and are thereby forced to respect the freedom of someone else’s conviction, when a person has realized that his dignity lies in his conviction and that respect for the dignity of someone else’s personality is respect for his own dignity.”

To realize the ideal, the individual must become a force.

“We need not only words, we need action. We need energetic, fanatical people who risk everything and are ready to sacrifice everything.”

But it turns out that these qualities are not enough for victory. We need to organize critically thinking individuals into a party capable of independent actions and influencing the people.

“But individuals... are only possible agents of progress. They become real leaders only when they are able to fight, when they are able to turn from insignificant units into a collective force, a representative of thought.”

As we can see, the main problem raised by the author of “Historical Letters” was the formulation of a new view on the role of the individual in history and modern life, in creating a theory of personality and in identifying the role and interaction in social progress and changing living conditions of three forces: the individual - the party - the masses.

“Historical Letters” are addressed to the intelligentsia, more precisely, to all those who think critically, who can rise above the level of modern life and develop a moral ideal that will serve as a banner for uniting units into a party, since the individual taken in itself is devoid of social power. The party, in turn, will rally the progressive forces of society around itself and, having penetrated the people, will go with them to revolutionary changes. For P.L. Lavrov, the initiator of social transformations is the individual, and the force capable of carrying out these transformations are the masses, who appear to be “the most energetic figures of progress.” Thus, a new theory arose - a “critically thinking personality”, the central point of which was the idea of \u200b\u200bthe duty of the intelligentsia to the people. The implementation of new forms of work and community life, previously developed by a critical personality, is the payment of the debt to the people.

Despite the idealistic basis for solving this problem, proposed by P.L. Lavrov’s ideas were in tune with the times, progressive, they mobilized the advanced forces of society to fight against the foundations of tsarist Russia. It is no coincidence that “Historical Letters” played a big role in the liberation movement of the post-reform period, being a theoretical expression of the revolutionary struggle of the heterodox intelligentsia of the era of populism and later the Narodnaya Volya. This is how N.S., mentioned above, evaluates Rusanov their influence on youth:

“Many of us... never parted with a small, tattered, scribbled, completely worn-out book. She was lying under our headboard. And while reading it at night, our hot tears of ideological enthusiasm fell on it, seizing us with an immense thirst to live for noble ideas and die for them.”

The motto of “Historical Letters” was: everything for the people (including one’s own life). In the development of the doctrine of sacrifice, “Historical Letters” were one of the most important links. Lavrov’s “Historical Letters” and “What is Progress?” Mikhailovsky formulated new theory personality and progress. Both authors, independently of each other, gave almost identical definitions of progress, emphasizing that its meaning lies in the harmonious development of the individual, in the individual’s struggle for individuality, for physical, mental and moral improvement. Progress is the goal and meaning of struggle. As for the individual, she is assigned the role of a lever of progress, its internal spring. Based on this, we can say that the theory of progress and personality theory of P.L. Lavrov’s works are unthinkable without the other; they can even be identified. Taken in its initial (criticism of the existing system) and final (realization of the ideal) points, this theory is equally acceptable for all currents of revolutionary thought in Russia in the post-reform period. This commonality is explained by the unity of the class nature of these movements. In addition, it is based on the traditions of the progressive intelligentsia serving the people. Throughout the history of the revolutionary movement, this service was dominated by an element of selflessness and doom. And if in Lavrov-Mikhailovsky’s personality theory the central point was the idea of struggle, duty and sacrifice, then everything else seemed illogical and unnatural. And the theory of personality itself appeared because the Russian reality of that time excluded the activity of the masses. Now it is easy to answer the question why the “Historical Letters” were addressed to the intelligentsia. There were no other forces capable of mastering the tasks of social reconstruction at that time.

February 15, 1870 Lavrov with the help of G.A. Lopatina fled from exile abroad. Contemporaries and historians explained this act in different ways. The fact is that Lavrov did not enjoy the reputation of a revolutionary at that time; he was considered an armchair scientist with a liberal way of thinking. According to N.S. Rusanov, the flight was caused by Lavrov’s desire to “participate in a living political struggle.” This opinion is completely rejected by researcher V. Vityazev, believing that Lavrov fled only to study scientific work. Now it can be considered proven that Lavrov’s escape was caused by political motives and is associated with the intention of revolutionary-minded youth to create a foreign press organ similar to Herzen’s “Bell”. So, N.A. Morozov points out that, while in exile, P.L. Lavrov expressed his consent to the Tchaikovsky members “to go abroad if he is given funds for an organ like Herzen’s Bell.” A.I. knew about the preparations for the escape. Herzen was ready to accept P.L. Lavrov at home, but this did not happen: in January 1870 A.I. Herzen died.

Abroad, Lavrov immediately established connections with members of the Russian section of the First International - A.V. Korvin-Krukovskoy, E.G. Barteneva and E.L. Dmitrieva. He received a set of issues of “People's Affairs”, which was of great importance, since this organ expressed the views of the young Russian emigration. It is known that “People's Affairs” as a theoretical journal began to be published in 1868 in Geneva and its first issue consisted entirely of articles written by M.A. Bakunin and N. Zhukovsky, which in itself already indicated his theoretical basis and political direction. The magazine presented in a condensed form the anarchist point of view on the tasks of the revolutionary struggle in Russia. He immediately found supporters in the Russian underground. However, already from the second issue, “People’s Cause” passed to N.I. Utin, since Bakunin left the editorial office. Then the magazine was transformed into a newspaper of the same name, which in March 1870 began to be published as the organ of the Russian section of the First International.

Like P.L. Lavrov’s attitude towards this organization is difficult to say, but he did not become a member of the Russian section of the First International, but joined it later, in the fall of 1870, on the recommendation of the famous figure in the French labor movement L. Varlin. It can be assumed that P.L. Lavrov did not approve of the struggle of the Russian section with M.A. Bakunin and his like-minded people and did not want to associate his name with the opponents of Bakuninism. He believed that the struggle within the party was harmful to the party itself and beneficial to its enemies. This constant desire to find a path to peace in the party at any cost was condemned by F. Engels in one of his letters to Lavrov.

“Every struggle,” wrote F. Engels, “contains moments when it is impossible not to give the enemy some pleasure, if you do not otherwise want to cause positive harm to yourself. Fortunately, we have advanced so far that we can give the enemy such private pleasure if at this price we achieve real success.”

His poem, written at the end of 1870, speaks about Lavrov’s mood and political views at that time. It expresses the idea of the necessity and inevitability of revolution and that one must rely only on the people who rise up in the name of brotherhood, equality and freedom. The poet deeply believes in the renewing mission of the upcoming revolution and exclaims:

Obviously, this orientation was the reason for the direct participation of P.L. Lavrov in the Paris Commune. He later became one of its first researchers. This fact is of exceptional interest. Lavrov’s letter to N. Stackenschneider dated May 5, 1871 contains the following lines:

“The struggle of Paris at the present moment is a historical struggle, and it is now truly in the first row of humanity. If he managed to defend himself, it would move history significantly forward, but even if he falls, if reaction triumphs, the ideas witnessed by several unknown people who emerged from the people, the real people, and became the head of government, these people will not die.”

These words are not the result of short-term inspiration and the delight of a heroic struggle; they set forth a holistic view, a concept for understanding one of the outstanding events of world history. When the terrible days of the death of the Commune arrived, the reactionary and liberal press poured out streams of dirty slander against the Communards. Lavrov was one of the first to write in those days:

“The Paris Commune of 1871 will be an important milestone in the human movement, and this date will not be forgotten.”

He retained this view of the Commune throughout his life. In 1875 he wrote:

“The revolution of 1871 was the moment when, from the larva of the fourth estate, a united humanity of working people emerged and declared its rights to the future. The great days of March 1871 were the first days in which the proletariat not only brought about a revolution, but also took charge of it. This was the first revolution of the proletariat."

He expressed the same thoughts, but even more reasoned, in 1879 in a speech about the Commune to Russian emigrants and in a special study - “March 18, 1871”, published in 1880 in Geneva. This work saves scientific significance and to the present time.

From the battlefield of the Parisian communards P.L. Lavrov emerged with an even stronger belief in the necessity and possibility of revolution in Russia. But on his native soil, at that time he could not pin his hopes on the working class. The experience of the Paris Commune helped Lavrov to finally get rid of the fluctuations between liberalism and democracy that took place in the 60s. It is also obvious that the Commune, if not generated, then at least strengthened his international feelings. P.L. Lavrov was alien to national narrow-mindedness; he promoted and theoretically developed revolutionary internationalism. In promoting the experience of the Commune, in educating Russian youth using its example, is one of the undoubted merits of P.L. Lavrov before the revolutionary history of Russia.

After the turbulent events of the Paris Commune, in the atmosphere of European reaction, Lavrov’s attention again and entirely turned to the state of affairs in Russia. Here at this time a new phase of the liberation movement began, associated with a new type of seventies revolutionary. The Tchaikovsky circle became a significant force in the social movement. It included talented people devoted to the revolution, some of them later played the role of active fighters against tsarism. The Tchaikovsky circle outlined an extensive plan of action, in which a large place was given to printed propaganda. In the spring of 1872, one of the members of the circle, young M.A., was sent abroad. Kupriyanov. He negotiated with Lavrov about the publication of the magazine “Forward”. The idea of creating a printed revolutionary organ turned out to be very popular, it was shared by people of various political directions of the underground. It seemed that he would unite them all. However, such a unification did not happen, and could not have happened due to the sharp differences in worldview and tactical plans adhered to by various emigration groups representing certain trends in Russia.

A small circle of like-minded people formed around Lavrov, among whom V.N. took an active position. Smirnov, S.A. Podolinsky and A.L. Linev. Even earlier, a circle of Bakunin direction arose (M.P. Sazhin-Ros, Z.K. Ralli, A.G. Elsints, etc.). Negotiations began between them about joint actions, and some time later it was planned to involve Tkachev, who had fled from Russia, in the work. But attempts to unite were unsuccessful, since the views of the parties turned out to be very different. Despite this, in August 1873 the first issue of the magazine “Forward” was published. From 1873 to 1877, five of his books were published, one of which (No. 4) was entirely occupied by P.L.’s monograph. Lavrov “The state element in the future society.” The fifth issue of the magazine was published without Lavrov’s participation. For two years (from January 1, 1875 to December 1876), a biweekly newspaper of the same name was published (48 issues in total). The soul of the whole affair was P.L. Lavrov.

The magazine Forward had a wide audience, and its influence was not limited to the underground. It is known, for example, that the magazine financially supported I.S. Turgenev. Lavrov and his friends largely inspired the great writer in his work. The goals and direction of the magazine were formulated in the first issue, in the article “Our Program”:

“Far from our homeland we are planting our banner, the banner of social revolution for Russia, for the whole world. This is not the business of a person, this is not the business of a circle, this is the business of all Russians who have realized that the real political order is leading Russia to destruction, that the real social system is powerless to heal its wounds. We don't have a name. We are all Russians who demand for Russia the domination of the people, the real people, all Russians who realize that this domination can only be achieved by a popular uprising, and who have decided to prepare this uprising, to make clear to the people their rights, their strength, their responsibilities.”

The fundamental task of the magazine, therefore, was to contribute to the preparation of a popular uprising by influencing the people through various means and, above all, propaganda. A prominent place in the program was occupied by the thesis about the main role of the masses in the revolutionary process. The opinion that Lavrov ignored the people in his sociological constructions is not only a mistake, but a distortion of historical fact.

“In first place,” wrote P.L. Lavrov, “we put forward the position that the restructuring of Russian society must be carried out not only for the purpose of the people’s good, not only for the people, but also through the people.”

In many of his works, written at different times, we encounter similar provisions dozens of times. These are not words and phrases taken out of context, but a harmonious system of views, the basis of P.L.’s entire worldview. Lavrova.

The main feature of the journalistic materials of “Forward” was their accusatory nature. IN AND. Lenin wrote about this kind of journalism:

“One of the main conditions for the necessary expansion of political agitation is the organization of comprehensive political denunciations. Otherwise, how can political consciousness and revolutionary activity of the masses be nurtured on these denunciations.”

Of the fifty-three issues of the magazine and newspaper, there is not a single one that does not contain criticism of the social system of Russia and its system of political governance. But among the numerous striking incriminating materials, two of the most revealing ones should be highlighted - the articles “Accounts of the Russian People” and “Samara Famine”, written by P.L. Lavrov. Here's what the first one said:

“It’s been 260 years since the Russian people, through a common effort, liberated Moscow from its enemies, defended the independence of the Russian land, and Zemsky Sobor Russian land elected the first Romanov as Moscow Tsar. Since then, scores began between the House of Romanov and the Russian people.”

We, Lavrov continued, have no personal enmity towards any of the emperors.

“We know that they were all spoiled and should have been spoiled by unlimited power.”

The power of kings and emperors could never benefit the people. Their actions are explained not by the subjective qualities of one or another monarch of Russia, but by the class nature of their power. The task, therefore, comes down not to replacing one emperor with another, but to destroying tsarism as a system of power.

How did the House of Romanov behave in relation to the development of science and free thought? - asked P.L. Lavrov.

“Let the Radishchevs and Novikovs answer this... let the thirty-year stifling reign of Nicholas answer, let modern Russian literature answer, with Herzen and Ogarev in exile, with Chernyshevsky and Mikhailov in hard labor, with departments without professors.”

“Not a single talented statesman; careerists, money-grubbers and simply swindlers - that’s who rules Russia, they are not interested in anything except personal gain, they will swear allegiance to anyone in the name of this gain... It’s time for the Russian people to put an end to the Romanovs’ scores that began 260 years ago.”

P.L. comes to this conclusion. Lavrov.

Even more impressive is the description of the famine in Russia made in the second article. Here are striking pictures of the misfortunes of the people in a number of provinces, and primarily in Samara. The causes of these disasters P.L. Lavrov saw in the Russian state system:

“The Russian state system everywhere sucks out all the strength of the Russian people and fatally leads them to degeneration. If this order continues for some time, it will inevitably exhaust all of Russia, the entire Russian people.”

The accusatory nature of Lavrov's journalism shows that in this sense he continued the work of Herzen, Belinsky, Chernyshevsky and other figures of the era of the fall of serfdom. Speaking about the role of Chernyshevsky in the liberation movement, P.L. Lavrov emphasized that Russian youth believed him most of all and that in terms of influence on them he had no equal among his contemporaries. Lavrov and Chernyshevsky were united, first of all, by the idea of revolution, confidence in the necessity and inevitability of a radical revolutionary transformation of Russia, as well as the socialist ideal in the name of which such a transformation should take place. However, in the area economic sciences and philosophy, Lavrov was in many ways inferior to Chernyshevsky.

IN common system Lavrov's views are central to his teaching on socialism. Almost all of his works, starting with “Historical Letters,” are subordinated to the idea of socialism. This is not accidental, because the meaning of the revolutionary struggle, according to P.L. Lavrov, there could only be socialism. Moreover, socialism for P.L. Lavrova is a natural and logical result historical development society. He invariably connected all the highest motives and the moral process of humanity with socialism. The ideas about socialism were formed by P.L. Lavrov was primarily influenced by the teachings of Herzen, as well as Western European utopian schools. The magazine “Forward” preached the theory of Russian utopian socialism:

“For the Russian there is a special soil on which the future of the majority of the Russian population can develop in the sense indicated common tasks of our time, there is a peasantry with communal land ownership. To develop our community in the sense of communal cultivation of the land and communal use of its products, to make the secular gathering the main political element of the Russian social system, to absorb private property into communal property, to give the peasantry that education and that understanding of their social needs, without which they will never be able to take advantage of their legal rights... - these are specifically Russian goals that every Russian who wants progress for his fatherland should contribute to.”

From these “specially Russian goals” a disdainful attitude towards the tasks of political struggle logically grew. At this point, the views of Lavrov and Bakunin largely converged. True, later, during the time of “Narodnaya Volya”, P.L. Lavrov put the tasks of political struggle in the first place, and in this sense he can be called a political revolutionary. However, the presence of elements of apoliticality - characteristic laurelism. This can be explained by the fact that Lavrov was a spokesman for the interests of the peasantry, which at that time showed a certain political indifference.

As already noted, Lavrov was influenced by the Paris Commune, as well as the works of K. Marx and F. Engels. All of the above-mentioned ideological sources are easily found in the journalism and scientific works of P.L. Lavrova. Here, however, we must immediately make a reservation: the diversity of theoretical influences did not deprive Lavrov’s point of view on socialism of originality and harmony. He considered the components of socialism to be the labor activity of all citizens according to their abilities and the economic well-being of everyone depending on the results of labor. In other words, the famous position of the Saint-Simonists, formulated in 1830 - “from each - according to his abilities, and to each - according to his deeds” - was completely assimilated and accepted by Lavrov. Moreover, the special importance of the economic side of the matter was emphasized:

"At the basis of everything social progress lies economic improvement. Without it, freedom, equality, liberal legislation, and a broad educational program are empty words. Poverty is slavery, no matter how the beggar is called - free or serf... The most excellent constitutions are a mockery of the people if pauperism deprives them of independence. The most progressive revolutions will not improve the social situation one bit if they do not touch upon economic issues.”

Another component of socialism P.L. Lavrov considered equal conditions for the education and cultural development of all citizens. Under socialism there can be no national, social, racial, etc. privileges. People are equal to each other, they are brothers. This was Lavrov’s idea of the ideal of the social system, that is, socialism. He said:

“Equality... does not at all consist in the perfect identity of all human individuals, but in the equality of their relations among themselves... A certain specialization of occupations, called division of labor by Adam Smith, can exist if only it turns out to be necessary or useful, but it is necessary that this specialization did not influence the relationships of people outside of work, so that it did not lead to class and castes, to the division of people into clean and dirty, into simple and difficult and, most importantly, into parasites and workers, into exploiters and exploited.”

As for the political forms of society under socialism, Lavrov did not give any definite answer on this matter.

The thought of P.L. seems extremely important. Lavrov that the masses on their own cannot develop a socialist ideology. It must be brought in from outside. Lavrov was confident that such eras in which movements like peasant wars under the leadership of Razin and Pugachev, went into a unique past. A new awakening is possible only as a result of the ideological influence of revolutionary elements on the masses. Propaganda itself must be based on the accuracy of facts, scientific criticism and absolute honesty, for “lying is a crime” in any revolutionary cause. Lavrov believed that socialism is “the result of historical development, the result of the history of thought. That is why it cannot develop itself among the masses, from their elementary common sense. It can and should be brought to the masses.” The above words indicate the enormous role assigned to P.L. Lavrov of the socialist-minded intelligentsia, who brought a new worldview to the people.

How now, after almost a hundred years, can one react to this thought? Taken on its own, it is certainly true. Indeed, not only the exploited people in general, but even the working class in particular cannot independently develop a socialist ideology. This ideology is introduced into the working environment from outside by the proletarian party. However, we should not forget that Lavrov’s very formulation of this problem was utopian. The masses of the pre-proletarian era, without the proletariat, can neither be the driving force of socialist transformations nor bearers of the ideas of socialism. Consequently, talk about introducing socialism from the outside turned out to be groundless at that time. Therefore, it is impossible to associate this position of Lavrov with the well-known thesis of V.I. Lenin on introducing socialist consciousness into the working environment. Despite this, however, the very fact of Lavrov’s theoretical searches in this direction undoubtedly individualizes and distinguishes him from the cohort of theorists of the 70s.

The following words of Lavrov attract attention:

“Our progress is not only the triumph of one class of people over another, of labor over monopoly, of knowledge over tradition, of association over competition. Our victory is something higher for us: it is the realization of the mental and moral goal of the development of the individual, society and all humanity.”

Naturally, for the sake of such an ideal and in its name, truly great revolutionaries could develop and mature. Socialist beliefs gave them unprecedented strength:

“This conviction will help us fight and die for the triumph of future generations, a triumph that we will not see.”

P.L. Lavrov believed that

“a revolutionary from a privileged environment must work for the benefit of the revolution, not because he feels bad, but because the people feel bad; he sacrifices his personal benefits, which his position in an absurd social order gives him.”

However, the idea of helping the people itself would not be so attractive if there were not a very important addition to it. It's about about future social development, about who it belongs to.

“The future,” Lavrov writes, “does not belong to predators who eat and destroy everything around them, who eat each other in an eternal struggle for a more delicious piece, for looted wealth, for domination over the masses and for the opportunity to exploit them. It belongs to people who set themselves human goals mutual development, the goal of theoretical truth and moral truth, people capable of acting together, together for a common goal, for the common good, for general development, for the implementation of the highest human ideals in life and social forms.”

However, despite many bright and expressive judgments about socialism and the need for its victory, Lavrism remained a utopia, since it did not take into account the working class as the only consistent fighter for socialism; in this regard, it does not go beyond the framework of pre-proletarian socialism. At the same time, we must not forget that the ideas of equality served at that time as the slogan of the revolutionary struggle and in this sense were of enormous importance.

Once an ideal has been developed, the means to implement it must be found. Such means can be varied, but the decisive one, according to Lavrov, was revolution. It is a historically inevitable and indispensable lever of social transformation. It should be emphasized that P.L. Lavrov was not a supporter of every revolution; he was interested in the people's revolution.

“The goal of the revolution,” he wrote, “is to establish a fair society, i.e. one where all will have the same opportunity to enjoy and develop, and all will have the same duty to work."

“The restructuring of Russian society must be carried out not only for the purpose of the people’s good, not only for the people, but also through the people.”

Lavrov considered the fact that there was no strong and organized bourgeoisie in Russia to be a positive development for the coming social revolution:

“Our bourgeoisie of landowners, merchants and industrialists has no political tradition, is not united in its exploitation of the people, itself suffers from the oppression of the administration and has not developed historical strength.”

The revolution, according to Lavrov, comes when

“when among the masses an intelligentsia is produced that is capable of giving popular movement an organization that could withstand the organization of their oppressors; or when the best part of the public intelligentsia comes to the aid of the masses and brings to the people the results of thought developed by generations, knowledge accumulated over centuries.”

Since the conditions of Russian life exclude the possibility of the emergence of an intelligentsia directly among the people, the idea of a union of the already existing intelligentsia with the people naturally came to the fore:

“Only the union of the intelligentsia of a few and the strength of the popular masses can give this victory.”

However, this kind of union does not arise by itself. He may be, according to P.L. Lavrov, only the result of long and persistent work and struggle. This work is hard and harsh, it requires serious and tireless workers. It is necessary, first of all, to break through to the people, to capture their attention and interests, to awaken in them a sense of search and desire to fight. The biggest obstacle on this path was the downtroddenness and inertia of the masses. It was necessary to overcome this obstacle, to get closer to the people, and hence the slogan - to go to the people in order to awaken them. It is known that this call fell on fertile soil and contributed to a broad movement of the intelligentsia into the midst of the workers and peasants. The very formulation of the question of bringing the democratic intelligentsia closer to the people after A.I. Herzen was no longer considered new. But it retained its relevance, and in the early 70s it acquired even greater political urgency due to the fact that the hopes of revolutionary figures for a spontaneous rise of the peasant movement did not materialize. Even that part of the intelligentsia that went to the people, not setting out to rouse them to revolution, but simply getting closer to them, did revolutionary work.

The idea of “simplifying” the intelligentsia in order to bring them closer to the people in the name of implementing revolutionary changes, justified and developed by Lavrov, seems to be a phenomenon that is certainly historically interesting. What to go to the people with and what to bring to them - this is one of the main questions posed by the magazine “Forward”. The main task of the settlers who find themselves in the midst of the people is to

“merging with the masses of the people... to form an energetic enzyme with the help of which the existing dissatisfaction with their situation among the people would be maintained and grew, an enzyme with the help of which fermentation would begin where it does not exist and would intensify where it exists.”

If legal ways to improve the situation of the masses are closed, “then there is only one path left - the path of revolution, one activity - preparation for revolution, propaganda in favor of it,” and “an honest, convinced Russian person in our time can see the salvation of the Russian people only on the path of radical, social revolution." The above words leave no doubt about why Lavrov called on young people to join the people and what tasks he set for them. This means that the thesis about the non-revolutionary nature of Lavrov’s propaganda disappears, as well as the assertion that “Forward” pursued educational rather than revolutionary goals.

Lavrov could not imagine implementing his revolutionary plans without seriously organizing an underground movement within Russia. For him, the revolutionary underground was nothing more than young Russia’s response to the reactionary actions of the government.

“The consequence of the first pressure on young people,” he wrote, “was the formation of “Land and Freedom.” The consequence of the persecution that followed the St. Petersburg fires, the closure of Sunday schools, and the condemnation of Chernyshevsky to hard labor was the formation of an embittered circle from which Karakozov emerged.”

The same government measures also give rise to an opposition that does not unite with the revolutionaries, but creates a favorable environment for them.

“The government of Alexander II finally developed, through its reactionary measures, an opposition in Russia, still unconscious, unorganized, but nevertheless ready to listen to the voices addressed to the Russian people with a revolutionary appeal.”

Lavrov's works were widely used by participants in the revolutionary movement. Suffice it to recall that they appeared in almost all political processes of those years. But, despite the consonance of the main ideas of the publication “Forward” with the needs of the social movement, new tactical and strategic plans matured in the revolutionary environment. After the failure of the campaign among the people and the defeat of underground organizations in the early 70s, a new situation arose in Russia. The victory of reaction persistently demanded an immediate reorientation of the revolutionary forces. There was a need to change both the tasks and forms of movement. New demands were placed on the journal “Forward” as a theoretical body. In the movement of the intelligentsia, a bias towards a purely populist side was clearly revealed in that specific understanding of populism, which had already developed by the time of the formation of “Land and Freedom”.

“Forward” and the Vperyodites did not share this new trend and continued to recognize the propaganda of the ideas of socialism as the main task of the day. There was a need to discuss new issues. Congress of representatives of revolutionary groups in Russia associated with the publication of P.L. Lavrov's "Forward", opened in Paris in early December 1876. Unfortunately, very little is known about this interesting event, which took place at the moment of a change in orientation and slogans. The congress was small. It was attended by delegates from three centers: Odessa, St. Petersburg and the London publishing circle “Forward”. The participation in his work of G. Popko, K. Grinevich, A. Linev, P. Lavrov, S. Ginzburg and V. Smirnov is reliably known. Lavrov did not name all the participants of the congress. He wrote about it this way:

“I do not name the rest of the people present at the congress, since for most of them I do not know how much the disclosure of their names could have harmed them; for some, and among the most influential, I know that they managed not to persecuted, and they now appear in the role of peaceful and well-meaning ordinary people.”

The congress showed that the views of the delegates were far from coinciding with what Vperyod advocated. Reports from the field were strongly critical of Lavrov's position. First of all, it was recognized that revolutionary activity cannot be limited to promoting the ideas of socialism. Propaganda by example is required. For these purposes, a centralized organization of revolutionaries is needed, capable of inciting protest and leading the movement, directing it in a certain direction. In other words, the revolutionary movement was taking on new tracks. Land Volunteerism became a new form of populism.

The speeches at the congress alarmed P.L. Lavrova. He treated the bearers of new ideas with great distrust and even suspicion. In a letter to a comrade from Kyiv P.L. Lavrov pointed out:

“I feel the need to be sure that we really agree on our ideals of social revolutionary activity; that the propagandists who march under the same banner with me really do propagandize, i.e. recruit, group and organize revolutionary forces, and do not limit themselves to factoring, distributing books and pamphlets, without at all thinking of implementing what is said in the latter, without at all trying to expand and refresh their circle with new forces, but, on the contrary, making it a closed circle of nepotism and monopolies. Before I enter into an obvious connection with circles, providing them with the publication and distribution of my works, I need to know whether I can accept moral responsibility for their activities in Russia.”

Lavrov expressed particular concern and dissatisfaction with regard to the circle in St. Petersburg. He wrote:

“In the decisions taken at the congress in December 1876, my only desire was to stand apart from the circle of St. Petersburg residents, without at the same time harming the continuation of business.”

The St. Petersburg circle, as is known, emphasized propaganda and agitation among the people, and not among the intelligentsia, and wanted to give its propaganda the character of open struggle.

The decisions of the Paris congress came as a surprise to Lavrov and determined the turn in his political life. He refused to edit Vperyod and broke ties with the Petersburg underground. With the new organization “Land and Freedom” that emerged in St. Petersburg at the end of 1876, P.L. Lavrov had no direct contacts, and the landowners did not show initiative in this regard. From that time on, the ideas and tactical guidelines of Bakunin decisively won in the revolutionary underground of the north of Russia. But, despite this seemingly unconditional defeat, P.L. Lavrov never ceased to influence the revolutionary movement in Russia.

The turning point in the revolutionary movement, which was expressed in the collapse of “Land and Freedom” and the formation of “Narodnaya Volya” and “Black Redistribution”, as well as in the aggravation of the political situation within the country, was reflected in Lavrov’s position. The movement of the Land Volyas concerned him little, but the activities of the People's Volya captured his entire attention and captivated him. Not immediately, after a critical analysis of the Narodnaya Volya program by P.L. Lavrov saw in the Narodnaya Volya movement a great force that expressed popular protest and popular ideals. In turn, for the Narodnaya Volya it was not indifferent which side Lavrov was on, with whom the Russian revolutionary underground always reckoned. The Executive Committee established contacts with him and entrusted him with representing the interests of Narodnaya Volya outside Russia. P.L. Lavrov carried out this responsible assignment with exceptional conscientiousness, understanding the importance of this mission. He often managed to sway European public opinion towards the Narodnaya Volya. Under his influence, the French government refused to extradite the famous Narodnaya Volya member L.A. to Russia. Hartmann. P.L. Lavrov became one of the initiators and organizers of the foreign Red Cross “People's Will”. Together with L.A. Tikhomirov and M.N. Oshanina, he published and edited the “Bulletin of the People’s Will”. Some of his major works were also placed there. P.L. Lavrov, in essence, turned out to be one of the most consistent defenders of the Narodnaya Volya ideology. He deeply believed that Narodnaya Volya was then the most progressive form of struggle against tsarism and that it raised the prestige of the Russian revolutionary to unprecedented heights. P.L. Lavrov resolutely opposed those who equated Narodnaya Volya with terrorism. It is necessary to distinguish, he said, the principled side of Narodnaya Volya from the forms into which it can develop under certain historical conditions.

Figures from other political directions also listened to Lavrov’s advice. The famous revolutionary E. Durnovo wrote to him at the end of May 1881:

“On behalf of the Moscow populist circle, I am writing to you with a request... to present your view of terrorism. Your feedback is eagerly awaited in Russia. Everything that comes from your pen is always read and read with great interest, and your review at this time on such an important issue will bring undoubted benefit to young people, so its early appearance is extremely desirable. Whatever the size of the article, we will immediately print it either as a separate brochure or in the next issue of “Black Redistribution.”

P.L. Lavrov defined his attitude towards political terror as follows:

“Terror is an extremely dangerous weapon and remains dangerous in Russia; those who resort to it take on heavy responsibility. The Executive Committee of Narodnaya Volya took on this responsibility and was supported for a long time public opinion in Russia, attracted a significant number of its living forces. Whether he was mistaken or not, I do not dare to judge, since final failure is not proof of an error in the theory.”

After the death of Narodnaya Volya, its mistakes became more or less clear. They rightly included an excessive passion for terrorism. But Lavrov continued to consider Narodnaya Volya the most acceptable form of struggle. He failed to understand that changing conditions required new forms of struggle. What was truly revolutionary yesterday has become a mistake today. On this occasion, V.I. Lenin wrote:

“When history takes a sharp turn, even the leading parties for more or less a long time cannot get used to the new situation; they repeat slogans that were correct yesterday, but have lost all meaning today.”

This kind of dialectic of ideas and slogans turned out to be alien to Lavrov. That is why he misunderstood a lot, had a negative attitude towards Plekhanov’s “Emancipation of Labor” group, and for a long time did not see either opportunities or prospects in the development of the Social Democratic movement. Only at the end of his life did he overcome this mistake.

It is important to note that at a time when it seemed that the reaction had completely triumphed, when the revolutionary underground was suppressed with terrible cruelty, Lavrov continued the fight. In this regard, it is appropriate to recall the words of V.I. Lenin that

“A revolutionary is not the one who becomes revolutionary when the revolution comes, but the one who, in the midst of the greatest reaction, in the greatest hesitation of liberals and democrats, defends the principles and slogans of the revolution.”

Lavrov’s main field at this time was literary activity, criticism of decadent theories and reactionary doctrines. These goals were served by many of his speeches and, above all, by the article “The Teaching of Gr. L.N. Tolstoy." The article developed the ideas and traditions of the democratic press about Tolstoy. As highly as the democratic press rated Tolstoy as a writer, it was so critical of his teaching and work as a preacher. Published in the late 70s - early 80s, Tolstoy’s works “Confession”, “On Non-Resistance to Evil”, “What Is My Faith”, “Master and Worker” and others carried ideas dangerous to social progress. The theoretical positions, advice and thoughts about morality contained in these works by V.I. Lenin called “the anti-revolutionary side of Tolstoy’s teachings.” P. L. Lavrov, with the decisiveness appropriate for this case, came out with a consistent criticism of Tolstoy’s entire system of philosophical views. This speech was also important because after the closure of Otechestvennye Zapiski, Tolstoyism was not subjected to critical assessments from the standpoint of revolutionary democracy. Lavrov saw Tolstoyism as a temporary phenomenon and defined it as a kind of disease. The fight against painful phenomena in social life was complicated by the disorder of the revolutionary underground and discord in its ranks. An expression of this was the open renegadeism of L. Tikhomirov, who had long been considered an outstanding revolutionary. His pamphlet “Why I Stopped Being a Revolutionary?”, diligently distributed by the police throughout Russia, made a painful impression. In this situation, Lavrov rose to the occasion. He explained the reasons for Tikhomirov's fall and, with even greater persistence, continued to instill in the minds of young people the belief in the inevitability of the revolution and its inevitable victory. His propaganda of those years, his work during the period of reaction, are full of optimism, confidence that there are forces in Russia that will renew it.

In 1892–1896 P.L. Lavrov took part in the publication of the collections “Materials for the history of the Russian social revolutionary movement” and placed in them his articles “The History of Socialism and the Russian Movement” and “The Populists 1873–1878.” In the legal press, under various pseudonyms, he appeared in several publications, but especially a lot of his correspondence and articles were published in Russkie Vedomosti, one of the most progressive newspapers of that time. At the end of his life, in the late 90s, P.L. Lavrov prepared several works that were published under the pseudonyms “S. Arnoldi" and "A. Dolengi.” Among them, we should note “Tasks of understanding history”, “Who owns the future”, “Vital issues”. the main idea all these works are expressed in the following words:

“We, Russian people of all shades of love for the people, all ways of understanding their good, must each work in our own place with our own tools, strive for one goal, common to all and special for us, Russians. Here, a formidable responsibility lies with Russian youth, who are ready to enter the 20th century and who will have to create the history of this century.”

* * *

With the name P.L. Lavrov is connected with a whole direction of social development in post-reform Russia. His works served the cause of the revolutionary education of the people and largely retain scientific significance in our time, although the worldview of P.L. Lavrov was not characterized by dialectics. He was characterized by abstract thinking, doctrinaire conclusions, isolation from real life, and a lack of understanding of the forces of revolution that were maturing in the depths of Russia. This explains why Lavrov found himself behind the movement during the period of the activities of “Land and Freedom”, failed to understand the crisis of the Narodnaya Volya in the early 80s and was unable to appreciate historical meaning social democratic movement at its initial stage. But Lavrov’s teachings about the individual and the intelligentsia, about socialism, and especially his theory of morality contain deep thoughts that have scientific significance. Isolating these thoughts from utopias is an interesting and advisable task.

Svatikov S.G. Social movement in Russia. Rostov n/d, 1905; Bogucharsky V. Active populism of the 70s. M. 1912; Thun A. History of revolutionary movements in Russia (the book was published in 1882 and went through several editions, among them the most interesting for its applications was published in 1923); Kornilov A. Social movement under Alexander II. M., 1909; Glinsky B. Revolutionary period of Russian history. M., 1912; and many others.

Pajitnov K.A. Development of socialist ideas in Russia. T. 1. Kharkov, 1913. P. 142.

Pokrovsky M.N. Russian history in the most concise outline. M., 1934; His own. Russian historical literature in class light. M., 1935.

Knizhnik-Vetrov I.P.L. Lavrov. M., 1930; Gorev B. P. L. Lavrov and utopian socialism. // Under the banner of Marxism. 1923. No. 6-7.

Lavrov P.L. Selected works. T. 1. P. 199.

Right there. P. 202.

Right there. pp. 253-254.

Right there. P. 261.

Right there. P. 228.

The past. 1907. No. 2. P. 261.

G.A. Lopatin. Sat. Art. Pg., 1922. S. 161, 164. See also: Voice of the Past. 1915. No. 10; 1916. No. 4. G.A. Lopatin describes this event as follows: “At the beginning of 1870, I had to come to St. Petersburg from the Caucasus, from where I fled. Here I met the daughter of P.L. Lavrova - M.P. Negreskul, whose husband was at that time in the fortress on the Nechaev case. From M.P. Negreskul... I learned that Pyotr Lavrovich was terribly eager to escape from exile abroad... Having learned about Pyotr Lavrovich's desire to escape from exile, I immediately offered my services to his relatives... My duty was to take Lavrov away from exile and deliver him to St. Petersburg . Pyotr Lavrovich’s further journey abroad took place without my participation, exclusively with the assistance of his relatives.”

Right there. P. 12.. Ibid. P. 128.. Forward. 1874. No. 2. Section II. pp. 77, 78.

The concept of “populism”, which was established in literature and which we use now, is far from corresponding to what existed in those years. The following formula was the essence of populism in the understanding of the seventies: a revolutionary movement in the name of the conscious and direct demands of the people. The task of the Narodniks, therefore, was to place the revolutionary struggle on the basis of popular interests. Hence, the attitude towards the propaganda of abstract ideas of socialism changed. Agitation and propaganda by fact, deed, and life example were put in first place. One of the most famous figures of that time, A.D. Mikhailov, wrote: “People of this trend subordinated their theoretical ideals and sympathies to the urgent, acute needs of the people and therefore called themselves “populists” (Narodovolets A. Mikhailov. Collection of art. M.; Leningrad, 1925. P. 107).

Lavrov P.L. Populists propagandists. L., 1925. P. 258.

GA RF. F. 1762. Op. 1. D. 2. L. 7.

Right there. L. 8.

Right there. Op. 4. D. 175. L. 5.

Letter to comrades in Russia. Geneva, 1888. P. 18.

Lenin V.I. PSS. 5th ed. T. 34. P. 10.

Lenin V.I. PSS. 5th ed. T. 23. P. 309.

Lenin V.I. PSS. 5th ed. T. 20. P. 71.

Bulletin of the People's Will. Geneva, 1886. No. 5. P. 137.

Arnoldi S. Who owns the future. M., 1905. P. 225.

The defining principle of cognition and creativity Pyotr Lavrovich Lavrov(1823-1900) was scientific, scientific criticism.

Unlike the Marxists, who proceeded from objective criteria for assessing social phenomena and their restructuring, Lavrov paid more attention to the consciously purposeful activity of the individual aimed at transforming existing social relations and the social system. Trying to abstract from random subjectivism and voluntarism that distort reality, he substantiated the theory of ethical subjectivism, closely linking it with the theory of progress.

Lavrov associated the essence of political progress with “the elimination of any compulsory political agreement for individuals who agree with it, that is, with bringing the state element in society to a minimum.” This means, firstly, the destruction of separatist aspirations in the very bud; secondly, resolving the issue of the natural borders of states included in a single union; thirdly, bringing people together based on cultural and scientific interests.

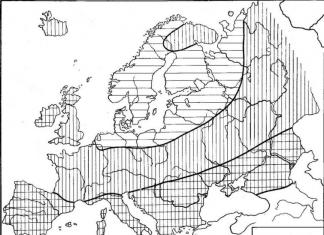

Reflecting on political progress, Lavrov argued that the desire to assimilate and reunite foreign nationalities, destroying their characteristics, is an anti-progressive fact. Lavrov recognized the rights of oppressed peoples Russian Empire to self-determination, even to the point of separation from it. At the same time, the political state union, according to Lavrov, is a powerful factor in the struggle for progress.

With the increasing influence in society of bourgeois immoralism based on “private capital ruling over the proletariat and exacerbating the class struggle,” the modern bourgeois state becomes the most invincible enemy of socialism and the proletariat. Therefore, unlike the Lassalleans, who considered it sufficient to seize the bourgeois state and use it for their own purposes, Lavrov called for its destruction, since it “in its essence is domination, it is inequality, it is a restriction of freedom.” “A right-wing state is no longer conceivable without the victory of labor in its struggle with capital.”

In justifying his ideal of socialism, Lavrov was strongly influenced by Marx, but, unlike him, he saw the basis of the world socialist movement not in the development of economic relations, but in ideology, in the similarity of the ideologies of certain classes in different countries. According to his concept, “socialism appeared on the stage of history as a demand for the solidarity of all mankind,” therefore workers’ socialism is the doctrine of the solidarity of the proletariat of all countries. The specificity of the application of this theory to Russian conditions is that the urban working class has broad support, a social basis for the solidarity of all workers in the village community, which within its own framework carries out joint cultivation of the land and common use of the products of labor.

Depending on the socio-economic, legal and spiritual Russian traditions, Lavrov also defines the goals of socialism.

The main ones are public property, social labor, federation of workers, which are carried out by the working people under the leadership of a small group of well-organized intelligentsia.

Social justice can only be achieved through a socialist revolution that creates a people's federation of Russian communities. In his work “The State Element in the Future Society” (1876), Lavrov explains the reason for the proletariat’s turning to this only means by the fact that “the rulers of the world and the leaders of the modern state will not voluntarily yield their advantageous position to the working proletariat... There is no reconciliation between the modern state and workers’ socialism , there is no agreement and there cannot be." Lavrov was confident that socialism had a better chance in the struggle between the modern state and the workers; the victory of the proletariat was fatally predetermined.

Under socialism, Lavrov completely excludes any dictatorship, believing that “every dictatorship spoils the best people.” He does not even allow the idea that one person could have power in all spheres of public life. The largest personality will participate only in some forms of power and in an equally significant proportion of branches of public life will occupy subordinate positions. For each special case there will be its own elected authority.

The new model of “Russian socialism” proposed by Lavrov and the plan for its implementation on an ethical and scientific basis had a huge ideological influence on enthusiasts of the 70s. XIX century in the West and in Russia, ready to live and die for noble goals.

The revolutionary populists hoped that they could save the Russian people from the capitalist economic system, overthrowing the autocracy and landowners, and establishing people's power. By fighting for the liquidation of noble land ownership and the transfer of land to peasant communities, the populists thereby fought for a peasant-bourgeois solution to the agrarian problem.

Populism was based on faith in the communal system of the peasant economy, in the special way of Russian folk life. Idealizing the peasant community, the populists viewed it as the embryo of a future socialist society. At the same time, some ideologists of populism, in particular P.L. Lavrov, noted the significant role of capitalism in preparing the economic prerequisites for socialism.

A characteristic feature of the economic teachings of the revolutionary populists was the desire to change the existing system by raising the peasant masses to revolt. A large role in preparing peasants for the revolution was given to the enlightened part of the population - students and progressively minded intelligentsia. The populists of the 70s adopted the ideological heritage of N.G. Chernyshevsky, but also introduced new ideas into Russian economic thought. They gave an analysis of the new economic processes that arose as a result of the bourgeois peasant reform.

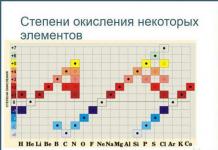

The ideologists of the main directions of revolutionary populism were M. A. Bakunin, P. L. Lavrov, P. N. Tkachev.

At the end of the 60s, in an atmosphere of hatred towards the tsar and the remnants of serfdom, inspired by faith in the revolutionary spirit of the people, circles of Nechaevites, Dolgushins and Bakuninists arose, whose representatives were convinced that it was only necessary to throw a spark into the people who had long been ready for revolution. Supporters of M.A. Bakunin considered the Russian people to be “born rebels” and relied on peasant revolts. This trend of revolutionary populism adhered to anarchist and rebellious tactics.

Supporters of P.L. Lavrov considered the main thing in preparing the revolution to be the propaganda of the ideas of socialism. However, Lavrov and a number of his followers, having become convinced that propaganda was hampered by the despotism of the tsarist political system, changed their tactics.

The ideas of conspiratorial tactics were developed by a representative of the third trend in populism, P. N. Tkachev. Tkachev’s supporters proceeded from the fact that the revolutionary intelligentsia cannot wait for a “nationwide revolt,” but must organize a revolutionary conspiracy and overthrow state power, supposedly “hanging in the air.”

Bakunism became a unique type of revolutionary populism in the second half of the 19th century. Its founder was Mikhail Aleksandrovich Bakunin (1814-1876). He went beyond the “noble revolutionism” of the Decembrists, and then Herzen, and became a revolutionary democrat. Bakunin was a defender of the peasants, firmly believing in the revolutionary impulses of the common people and hoping for the emergence of a new Pugachev in Rus'.

The popularity of M. A. Bakunin was explained by the fact that, while criticizing serfdom and tsarism, he called young people to revolution, and he himself participated in the revolution of 1848-1849. V Western Europe, was a prisoner of the Peter and Paul and Shlisselburg fortresses, a comrade-in-arms of Herzen and Ogarev, and advocated for the freedom and unity of the Slavic peoples. True, he put forward the slogans of anarchism, but in Russia the revolutionary democratic ideas and calls of Bakunin were perceived predominantly.

The main works of M. A. Bakunin: “The People’s Cause: Romanov, Pugachev, Pestel”, “Our Program”, “In Russia”, “Federalism and Socialism”, etc.

Bakunin's socio-economic views took shape in the context of preparations for the reform of 1861. Already in the 50s, he predicted the inability of the Russian government to carry out a reform that would truly improve the situation of the people. He argued that the shortcomings of the empire could not be addressed without affecting the interests of the government.

Criticism of capitalism, which was of a progressive nature, occupied a large place in Bakunin’s works. Exposing the bourgeois order, he used a number of provisions of K. Marx, set out in the first volume of Capital. Bakunin described class contradictions in bourgeois society, the ruthless exploitation of the people by the bourgeoisie, the prosperity of which, as he noted, is based “on poverty and on the economic slavery of the proletariat” 4 [Bakunin M.A. Knuto-German Empire and Social Revolution // Izbr. op. T. 2. M.; Pg., 1919. S. 26-27]. Bakunin's views on property were predetermined by his theory of the abolition of the right of inheritance. Bakunin waged a constant struggle with the defenders of capitalist society, emphasizing the class character of bourgeois science. Debunking the demagogic slogans of the bourgeoisie about freedom, he revealed the true essence of bourgeois freedoms: this is “nothing more than the opportunity to exploit the labor of workers by the power of capital” 5 [Bakunin M.A. Sleepers // Ibid. T. 4. P. 34]. He considered the source of “people's wealth” to be “people's labor”, which was given over to the plunder of stock exchange speculators, swindlers, rich owners and capitalists.

Bakunin wrote about the division of labor into mental and physical and believed that in the future society people of mental labor “will turn... the discoveries and applications of science for the benefit of everyone and, above all, for the facilitation and ennoblement of labor, this only legitimate and real basis of human society” b [Bakunin M.A. Comprehensive education//Ibid. P. 49-50]. He advocated the organization of a “large community” in a future socialist society.

Bakunin's trend in populism had an anarchist overtones. Bakunin transferred his hatred of the tsarist monarchy and the bourgeois states of Western Europe to the state in general, declaring that any power gives rise to exploitation. Advocating the revolutionary destruction of the state, he pictured socialism as a free federation of workers' associations and agricultural communities, based on self-government and absolute individual freedom. Driving force Bakunin considered the revolutionary upheaval to be the peasantry, as well as the urban poor and declassed elements. Since, in his opinion, the people are always ready for an uprising, the impetus for the start of the revolution should be given by rebel revolutionaries. In the mid-60s, Bakunin created the anarchist organization “International Alliance of Socialist Democracy”, which in 1868 was admitted to the First International. In 1872, Bakunin and members of his organization were expelled from the First International for subversive activities.

In Russian conditions, Bakunin's revolutionary-democratic concepts were directed against serfdom and tsarist autocracy and were of a progressive nature. But in Western Europe, in countries with a developed labor movement, his anarchism acquired reactionary features. K. Marx and F. Engels revealed the bourgeois; the essence of anarchist theories. V.I. Lenin described Bakunism as one of the forms of non-proletarian pre-Marx socialism, generated by the despair of the petty bourgeoisie.