History of Russia XVIII-XIX centuries Milov Leonid Vasilievich

§ 4. Eastern question

§ 4. Eastern question

Ottoman Empire and European Powers. At the beginning of the 19th century, the Eastern question did not play a noticeable role in Russian foreign policy. The Greek project of Catherine II, which provided for the expulsion of the Turks from Europe and the creation of a Christian empire in the Balkans, the head of which the empress saw her grandson Constantine, was abandoned. Under Paul I, the Russian and Ottoman empires united to fight revolutionary France. The Bosphorus and Dardanelles were open to Russian warships, and FF Ushakov's squadron successfully operated in the Mediterranean. The Ionian Islands were under the protectorate of Russia, their port cities served as a base for Russian warships. For Alexander I and his "young friends" the Eastern question was the subject of serious discussion in the Secret Committee. The result of this discussion was the decision to preserve the integrity of the Ottoman Empire, to abandon the plans for its partition. This was contrary to the Catherine's tradition, but was fully justified in the new international conditions. The joint actions of the governments of the Russian and Ottoman empires ensured relative stability in the Black Sea region, the Balkans and the Caucasus, which was important against the general background of European upheavals. It is characteristic that the opponents of the balanced course in the Eastern question were FV Rostopchin, who were nominated under Paul I, who proposed detailed projects for the partition of the Ottoman Empire, and the reputed leader N. M. Karamzin, who considered the collapse of the Ottoman Empire "beneficial for reason and humanity."

At the beginning of the XIX century. for the Western European powers, the Eastern question was reduced to the problem of the "sick man" of Europe, which the Ottoman Empire was considered to be. From day to day, her death was expected, and it was about the division of the Turkish inheritance. England, Napoleonic France and the Austrian Empire were especially active in the Eastern question. The interests of these states were in direct and acute contradiction, but on one thing they were united, seeking to weaken the growing influence of Russia on affairs in the Ottoman Empire and in the region as a whole. For Russia, the Eastern question consisted of the following aspects: the final political and economic establishment in the Northern Black Sea region, which was mainly achieved under Catherine II; recognition of her rights as the patroness of the Christian and Slavic peoples of the Ottoman Empire and, above all, the Balkan Peninsula; the favorable regime of the Black Sea straits of the Bosphorus and the Dardanelles, which ensured its commercial and military interests. In a broad sense, the Eastern Question also touched on Russian policy in the Transcaucasus.

Accession of Georgia to Russia. The cautious approach of Alexander I to the Eastern question to a certain extent was due to the fact that from the first steps of his rule he had to solve a long-standing problem: the annexation of Georgia to Russia. The Russian protectorate over Eastern Georgia, proclaimed in 1783, was largely formal in nature. Severely affected by Persian invasion in 1795, Eastern Georgia, which made up the Kartli-Kakhetian kingdom, was interested in Russian patronage and military protection. At the request of Tsar George XII, Russian troops were stationed in Georgia, an embassy was sent to St. Petersburg, which was supposed to seek that the Kartli-Kakhetian kingdom "was considered belonging to the Russian state." At the beginning of 1801, Paul I issued a Manifesto on the annexation of Eastern Georgia to Russia on special rights. After some hesitation caused by disagreements in the Permanent Council and in the Secret Committee, Alexander I confirmed his father's decision and on September 12, 1801 signed a Manifesto to the Georgian people, which liquidated the Kartli-Kakhetian kingdom and annexed Eastern Georgia to Russia. The Bagration dynasty was removed from power, and a Supreme Government was created in Tiflis, made up of Russian military and civilians.

P. D. Tsitsianov and his Caucasian policy. General PD Tsitsianov, a Georgian by birth, was appointed as the chief administrator of Georgia in 1802. Tsitsianov's dream was the liberation of the peoples of Transcaucasia from the Ottoman and Persian threats and their unification into a federation under the auspices of Russia. Acting energetically and purposefully, in a short time he achieved the consent of the rulers of the Eastern Transcaucasia to annex the territories under their control to Russia. Derbent, Talysh, Cuban, Dagestan rulers agreed to the patronage of the Russian tsar. Tsitsianov undertook a successful campaign against the Ganja Khanate in 1804. He began negotiations with the Imeretian king, which later ended with the inclusion of Imeretia in the Russian Empire... In 1803, the ruler of Megrelia passed under the protectorate of Russia.

Tsitsianov's successful actions aroused the discontent of Persia. The Shah demanded the withdrawal of Russian troops from Georgia and Azerbaijan, which was ignored. In 1804, Persia began a war against Russia. Tsitsianov, despite the lack of forces, conducted active offensive operations - the Karabakh, Sheki and Shirvan khanates were annexed to Russia. When Tsitsianov accepted the surrender of the Baku khan, he was treacherously killed, which did not affect the course of the Persian campaign. In 1812, the Persian crown prince Abbas Mirza was utterly defeated by General PS Kotlyarevsky at Aslanduz. The Persians were supposed to clear the entire Transcaucasia and negotiate. In October 1813, the Gulistan Peace Treaty was signed, according to which Persia recognized Russian acquisitions in the Transcaucasus. Russia received the exclusive right to keep warships in the Caspian Sea. The peace treaty created a completely new international legal position, which meant the approval of the Russian border along the Kura and Araks and the entry of the peoples of the Transcaucasus into the Russian Empire.

Russian-Turkish War 1806-1812 Tsitsianov's active actions in the Transcaucasus were apprehended with caution in Constantinople, where French influence noticeably increased. Napoleon was ready to promise the Sultan the return of Crimea and some Transcaucasian territories under his rule. Russia considered it necessary to agree to the proposal of the Turkish government on the early renewal of the union treaty. In September 1805, a new treaty of alliance and mutual assistance was concluded between the two empires. Of great importance were the articles of the treaty on the regime of the Black Sea straits, which during the hostilities Turkey undertook to keep open to the Russian navy, while not allowing the warships of other states to enter the Black Sea. The agreement did not last long. In 1806, incited by Napoleonic diplomacy, the Sultan replaced the pro-Russian rulers of Wallachia and Moldavia, to which Russia was ready to respond by introducing its troops into these principalities. The Sultan's government declared war on Russia.

The war, started by the Turks with the expectation of weakening Russia after Austerlitz, was fought with varying degrees of success. In 1807, having won a victory at Arpachai, Russian troops repulsed the attempt of the Turks to invade Georgia. The Black Sea Fleet forced the Turkish fortress of Anapa to surrender. In 1811 Kotlyarevsky took the Turkish fortress of Akhalkalaki by storm. On the Danube, military operations took on a protracted nature until, in 1811, MI Kutuzov was appointed commander of the Danube army. He defeated the Turkish forces at Ruschuk and Slobodzeya and forced Porto to conclude peace. This was the first huge service rendered by Kutuzov to Russia in 1812. Under the terms of the Bucharest Peace, Russia received the rights of the guarantor of Serbia's autonomy, which strengthened its position in the Balkans. In addition, she received naval bases on the Black Sea coast of the Caucasus and part of Moldova between the Dniester and Prut rivers departed to her.

Greek question. The system of European equilibrium established at the Vienna Congress did not extend to the Ottoman Empire, which inevitably led to an aggravation of the Eastern question. The sacred union meant the unity of the European Christian monarchs against the infidels, their expulsion from Europe. In fact, the European powers waged a fierce struggle for influence in Constantinople, using the growth of the liberation movement of the Balkan peoples as a means of pressure on the Sultan's government. Russia made extensive use of its opportunities to provide patronage to the Sultan's Christian subjects - the Greeks, Serbs, and Bulgarians. The Greek question has become especially acute. With the knowledge of the Russian authorities in Odessa, Moldavia, Wallachia, Greece and Bulgaria, Greek patriots were preparing an uprising aimed at the independence of Greece. In their struggle, they enjoyed broad support from the advanced European public, which viewed Greece as the cradle of European civilization. Alexander I showed hesitation. Proceeding from the principle of legitimism, he did not approve of the idea of Greek independence, but did not find support either in Russian society or even in the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, where I. Kapodistria, the future first president of independent Greece, played a prominent role. In addition, the tsar was impressed by the idea of the triumph of the cross over the crescent, the expansion of the sphere of influence of European Christian civilization. He spoke about his doubts at the Verona Congress: “Nothing without a doubt seemed more responsible public opinion countries like religious war with Turkey, but in the unrest of the Peloponnese, I saw signs of revolution. And he abstained. "

In 1821, the Greek national liberation revolution began, led by the general of the Russian service, aristocrat Alexander Ypsilanti. Alexander I condemned the Greek Revolution as a revolt against the legitimate monarch and insisted on a negotiated settlement of the Greek question. Instead of independence, he offered the Greeks autonomy within the Ottoman Empire. The rebels, who had hoped for direct help from the European public, rejected the plan. The Ottoman authorities did not accept him either. The forces were clearly unequal, the Ypsilanti detachment was defeated, the Ottoman government closed the straits for the Russian merchant fleet, and moved troops to the Russian border. To settle the Greek question, at the beginning of 1825, a conference of the great powers convened in St. Petersburg, where Britain and Austria rejected the Russian program of joint action. After the Sultan refused to mediate the conference participants, Alexander I decided to concentrate troops on the Turkish border. Thus, he crossed out the policy of legitimism and went on to openly support the Greek national liberation movement. Russian society welcomed the emperor's determination. A firm course in the Greek and, more broadly, the Eastern question was defended by such influential dignitaries as V.P. Kochubei, M.S. Vorontsov, A.I. They were worried about possible weakening Russian influence among the Christian and Slavic population of the Balkan Peninsula. A. P. Ermolov asserted: “Foreign offices, especially English, they put us guilty of patience and inaction before all peoples in a disadvantageous way. The end result is that in the Greeks, who are committed to us, we will leave a fair bitterness on us. "

A.P. Ermolov in the Caucasus. The name of A.P. Ermolov is associated with a sharp increase in the military-political presence of Russia in the North Caucasus, a territory that was ethnically diverse and whose peoples were at very different levels of socio-economic and political development. There were relatively stable state formations- Avar and Kazikumyk khanates, shamkhalstvo Tarkov, patriarchal "free societies" dominated in the mountainous regions, the prosperity of which largely depended on successful forays on the flat neighbors engaged in agriculture.

In the second half of the 18th century. The northern Ciscaucasia, which was the object of peasant and Cossack colonization, was separated from the mountainous regions by the Caucasian line, which stretched from the Black to the Caspian Sea and ran along the banks of the Kuban and Terek rivers. A postal road was laid along this line, which was considered almost safe. In 1817, the Caucasian cordon line was moved from the Terek to the Sunzha, which caused discontent among the mountain peoples, for thereby they were cut off from the Kumyk plain, where cattle were driven to winter pastures. For the Russian authorities, the inclusion of the Caucasian peoples in the orbit of imperial influence was a natural consequence of the successful establishment of Russia in the Transcaucasus. Militarily and economically, the authorities were interested in eliminating the threats that the raiding system of the highlanders concealed. The support that the highlanders received from the Ottoman Empire justified Russia's military intervention in the affairs of the North Caucasus.

Appointed in 1816 to the post of the chief commander of the civilian unit in Georgia and the Caucasus and at the same time the commander Separate building General A.P. Ermolov considered it his main task to ensure the security of Transcaucasia and the inclusion of the territory of mountainous Dagestan, Chechnya and the North-West Caucasus into the Russian Empire. From Tsitsianov's policy, which combined threats and monetary promises, he went on to abruptly suppress the raiding system, for which he widely used deforestation and the destruction of recalcitrant auls. Ermolov felt himself to be the "proconsul of the Caucasus" and was not shy about using military force. It was under him that the military-economic and political blockade of mountainous regions was carried out, he considered a demonstration of force and military expeditions the best remedy pressure on the mountain peoples. On the initiative of Ermolov, the fortresses of Groznaya, Vnezapnaya, Burnaya were built, which became strongholds for the Russian troops.

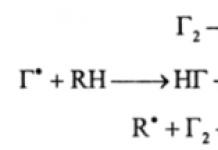

Ermolov's military expeditions led to opposition from the mountaineers of Chechnya and Kabarda. Ermolov's policy provoked a rebuff from the "free societies", the ideological basis for the rallying of which was Muridism, a kind of Islam adapted to the concepts of mountain peoples. The teaching of Muridism demanded from every faithful constant spiritual improvement and blind obedience to the mentor, the student, whose murid he became. The role of the mentor was exceptionally great, he combined spiritual and secular power in his person. Muridism imposed on its followers the obligation to wage a "holy war", ghazavat, against the infidels before their conversion to Islam or complete extermination. Appeals to ghazavat, addressed to all mountain peoples who professed Islam, were a powerful stimulus for resistance to Yermolov's actions and at the same time helped to overcome the disunity of the peoples inhabiting the North Caucasus.

One of the first ideologues of Muridism, Muhammad Yaragsky, preached the transfer of strict religious and moral norms and prohibitions to the field of social and legal relations. The consequence of this was the inevitable clash of Muridism, based on Sharia, a body of Muslim law, relatively new for the Caucasian peoples, with adat, the norms of customary law, which for centuries determined the life of "free societies". The secular rulers were wary of the fanatical preaching of the Muslim clergy, which often led to civil strife and bloody massacres. For a number of the peoples of the Caucasus who professed Islam, Muridism remained alien.

In the 1820s. the opposition of previously scattered "free societies" to Yermolov's straightforward and short-sighted actions grew into organized military-political resistance, the ideology of which was muridism. We can say that under Ermolov, events began, which contemporaries called the Caucasian War. In reality, these were actions of separate military detachments, devoid of a general plan, which either sought to suppress the attacks of the mountaineers, or undertook expeditions deep into the mountainous regions, without representing the enemy's forces and not pursuing any political goals. Military operations in the Caucasus have become protracted.

From the book The Truth About Nicholas I. The Swindled Emperor the author Tyurin AlexanderThe Eastern question in the interval between the wars of the Gunkyar-Skelessian Treaty of 1833 The Egyptian crisis put the Ottoman Empire on the brink of life and death, and determined its short-term rapprochement with Russia. The ruler of Egypt Megmed-Ali (Muhammad Ali) came from Rumelia,

the author Milov Leonid Vasilievich§ 4. Eastern question Ottoman Empire and European powers. At the beginning of the 19th century, the Eastern question did not play a noticeable role in Russian foreign policy. The Greek project of Catherine II, which provided for the expulsion of the Turks from Europe and the creation of a Christian empire in the Balkans,

From the book History of Russia XVIII-XIX centuries the author Milov Leonid Vasilievich§ 2. The Eastern question. Russia in the Caucasus The problem of the Black Sea straits. Relying on the Petersburg Protocol of 1826, Russian diplomacy forced the Ottoman authorities to sign the Akkerman Convention in October of the same year, according to which all states received the right

From the book Russia and Russians in World History the author Narochnitskaya Natalia AlekseevnaChapter 6 Russia and the World Eastern Question The Eastern question is not one of those that are subject to the solution of diplomacy. N. Ya.Danilevsky. "Russia and Europe" The transformation of Russia into Russia took place by the second half of the 18th century, and by the second half of the next, 19th century in

From the book The Course of Russian History (Lectures LXII-LXXXVI) the authorEastern question So, in the course of the XIX century. the southeastern borders of Russia are gradually being pushed back beyond their natural boundaries by the inevitable linkage of relations and interests. Russia's foreign policy on the southwestern European borders differs in a completely different direction. I AM

From the book The Course of Russian History (Lectures XXXIII-LXI) the author Klyuchevsky Vasily OsipovichThe Eastern question Bogdan, who was already dying, again stood in the way of friends and foes, both states, and the one to whom he betrayed, and the one to whom he swore allegiance. Frightened by the rapprochement between Moscow and Poland, he entered into an agreement with the Swedish king Charles X and the Transylvanian

From the book of Attila. Scourge of god the author Bouvier-Azhan MauriceVII THE EASTERN QUESTION Attila's manner of actions at the walls of Constantinople always raised many questions, and indeed, even if the perspective brutal war with Aspar was more than likely, even if the storming of the city promised to be extremely difficult, despite the successes of Edecon in the matter

From the book History of Romania author Bolovan IoanThe Romanian Principalities and the "Eastern Question" The evolution of the "Eastern Question", the progress caused by the French Revolution, and the spread of the revolutionary spirit in South-Eastern Europe also affected the political situation in the Romanian principalities. At the end of the 18th century, in a close

From the book History of Romania author Bolovan Ioan"Eastern question" and the Romanian principalities "Eteria" and the revolution of 1821 under the leadership of Tudor Vladimirescu. It is indisputable that the French Revolution and especially the Napoleonic Wars gave at the beginning of the 19th century. "Eastern question" new meaning: defending the national idea,

From the book of Compositions. Volume 8 [Crimean War. Volume 1] the author Tarle Evgeny Viktorovich From the book Alexander II. Spring of Russia the author Carrer d'Ancausse HeleneThe eternal "Eastern question" The "Union of three emperors" concluded in 1873 revealed its fragility in the face of the Balkan question. The fate of the Slavic peoples, who were under the heel of the Ottoman Empire, was the subject of unceasing concerns of Russia. A significant contribution to the fact

From the book Volume 4. Reaction times and constitutional monarchies. 1815-1847. Part two author Lavisse Ernest From the book Patriotic History: Cheat Sheet the author author unknown54. "EASTERN QUESTION" The term "eastern question" is understood as a group of contradictions in the history of international relations from the end of the XVIII - beginning. XX century, in the center of which were the peoples who inhabited the Ottoman Empire. The solution of the "eastern question" as one of the main

From the book Russian Istanbul the author Komandorova Natalia IvanovnaThe Eastern question The so-called "Eastern question" was actually a "Turkish question" in relation to Russia, many scholars and researchers believe, since since the 15th century, its main content was Turkish expansion in the Balkan Peninsula and in the eastern

From the book Russia and the West on the Swing of History. From Paul I to Alexander II the author Romanov Petr ValentinovichThe Eastern question that spoiled everyone Nicholas I remained in history as a man who lost the Crimean (or Eastern) War, which broke out in 1853, in which Russia was opposed by a powerful coalition of European states, which included England, France, Turkey, Sardinia and

From book General history[Civilization. Modern concepts. Facts, events] the author Olga DmitrievaThe Eastern Question and the Problems of Colonial Expansion While the European political elite was comprehending the new realities that arose after the Franco-Prussian war, the unification of Germany and the formation in the center of Europe of a powerful and aggressive empire, clearly claiming leadership in

The most difficult international problem of the second half of the 19th century. arose in connection with the collapse of the Ottoman Empire. What will happen in her place? In diplomacy, this problem is known as the "Eastern Question". The most difficult international problem of the second half of the XIX century. arose in connection with the collapse of the Ottoman Empire. What will happen in her place? In diplomacy, this problem is known as the "Eastern Question".

By the end of the 18th century, it became clear that the once formidable state of the Ottoman Turks was in decline. Russia and Austria benefited most from this process in the 18th century. Austria conquered Hungary and Transylvania and penetrated the Balkans. Russia expanded its borders to the shores of the Black Sea, hoping to advance into the Mediterranean. Many Balkan peoples were brothers-Slavs, Bulgarians and Serbs, moreover, brothers in faith, and the Russians considered their liberation a fully justified deed.

But by the 19th century, expelling the "Turk" was no longer so easy. All countries, including Austria and Russia, were hostile to revolutions directed against the established order, and were worried about the possibility of a complete collapse of the Turkish state. Britain and France, which had their own interests in the region, sought to prevent Russian expansion, fearing that the liberated Slavs might turn into satellites of Russia. However, public opinion was outraged by the frequent massacres perpetrated by the Turks, and it was difficult for Western governments to support the Sultan. The situation was complicated by the growing unrest among the Balkan peoples. Not having enough strength to expel the Turks themselves, they could well create a crisis that would require international intervention.

Revolt in Greece

First, such a crisis arose in connection with the uprising in Greece in 1821. Public support for the Greeks and reports of Turkish atrocities forced the West to act. When the sultan refused to accept the imposed solution to the problem, the Anglo-French-Russian expedition destroyed the Egyptian and Turkish fleets in the Battle of Navarino (1827), and the Russian invasion (1828-29) forced the Turks to submit. According to a treaty signed in London in 1830, Greece was recognized as an independent kingdom. Three other Balkan provinces - Serbia, Wallachia and Moldavia - received autonomy (self-government) within the Ottoman Empire.

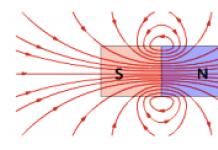

In the 30s of the XIX century, the Ottoman Middle Eastern possessions were in the center of the Eastern question. The ruler of Egypt, Mehmet Ali, conquered Syria from the Ottoman Empire (his nominal overlord), but British intervention restored the status quo. In the course of events, another important problem arose - the right to pass through the narrow straits of the Bosphorus and Dardanelles controlled by Turkey, connecting the Black Sea with the Mediterranean. The international agreement (the Convention on the Straits of 1841) provided that no state has the right to conduct its warships through the straits while Turkey is at peace. Russia was increasingly opposed to this restriction. But it continued to operate until 1923.

Since the middle of the 19th century, Russia has twice waged victorious wars against Turkey, imposing tough terms of agreements on it, but other European powers forced them to revise them. This was first done during the conclusion of the Paris Peace in 1856, after the Crimean War (1854-56), in which Russia was defeated by Britain and France. The second agreement was reached at the Berlin Congress (1878) after a general conflict was barely avoided. However, the great powers were only able to slow down the formation of the Balkan states, which, moving from autonomy to independence, sometimes challenged the agreements adopted at international congresses. So, in 1862 Wallachia and Moldavia united, forming the Romanian principality, the full independence of which was recognized in 1878 simultaneously with the independence of Serbia. Although the Berlin Congress provided for the formation of two Bulgarian states, they merged (1886) and eventually achieved full independence (1908).

Balkanization

By that time, it became clear that the Turkish possessions in the Balkans would disintegrate into several separate states. This process made such an impression on politicians that any comparable fragmentation of a large state is still called balkanization. In a sense, the Eastern question was resolved after the First Balkan War (1912), when Serbia, Bulgaria, Montenegro and Greece entered into an alliance to expel the Turks from Macedonia, leaving only a patch of land under their rule in Europe. Borders have been redrawn. A new state appeared - Albania. The "Balkanization" is over. But the region did not come close to stability, and the fragmentation of the Balkans pushed the great powers into intrigue. Both Austria and Russia were deeply involved in them, since Austria-Hungary in two stages (1878, 1908) absorbed the Serbo-Croatian provinces of Bosnia and Herzegovina. Over time, the indignation of the Serbs will serve as a spark, from which World War I of 1914-18 flares up, causing the fall of the Austrian, Russian and Ottoman empires. But even after that, as the Yugoslav events of the 1990s showed, the Balkan conflicts were not resolved.

KEY DATES

1821 Greek uprising begins

1827 Battle of Navarino

1830 Recognition of the independence of Greece

1841 London Straits Convention

1854-56 Crimean War

1862 Formation of Romania

1878 Berlin Congress decides to create two Bulgarian states. Independence of Serbia and Romania. Austria gets the right to rule Bosnia and Herzegovina

1886 Unification of the two provinces to form Bulgaria

1908 Bulgaria becomes independent. Austria annexes Bosnia and Herzegovina

1912 First Balkan War

1913 Second Balkan War

1914 Assassination of the Austrian Archduke in Sarajevo leads to World War I

Causes

CRIMEAN WAR (1853-1856), the war between Russia and the coalition of the Ottoman Empire, Great Britain, France and Sardinia for domination in the Middle East.

The war was prompted by Russia's expansionist plans towards the rapidly weakening Ottoman Empire. Emperor Nicholas I (1825-1855) tried to use the national liberation movement of the Balkan peoples to establish control over the Balkan Peninsula and the strategically important straits of the Bosphorus and Dardanelles. These plans threatened the interests of the leading European powers - Great Britain and France, which were constantly expanding their sphere of influence in the Eastern Mediterranean, and Austria, which sought to establish its hegemony in the Balkans. The reason for the war was the conflict between Russia and France, connected with the dispute between the Orthodox and Catholic Churches for the right of custody. over the holy places in Jerusalem and Bethlehem, which were in Turkish possessions. The growth of French influence at the Sultan's court caused concern in St. Petersburg. In January-February 1853 Nicholas I proposed to Great Britain to agree on the division of the Ottoman Empire; however, the British government preferred an alliance with France. During his mission to Istanbul in February-May 1853, the Tsar's special representative, Prince A.S. Menshikov, demanded that the Sultan agree to a Russian protectorate over the entire Orthodox population in his domain, but he, with the support of Great Britain and France, refused. June 21 (July 3) Russian troops crossed the river. Prut and entered the Danube principalities (Moldavia and Wallachia); the Turks made a sharp protest. An attempt by Austria to reach a compromise agreement between Russia and the Ottoman Empire in July 1853 was rejected by the Sultan. On September 2 (14), the combined Anglo-French squadron approached the Dardanelles. On September 22 (October 4), the Turkish government declared war on Russia. In October, Turkish troops tried to gain a foothold on the left bank of the Danube, but were driven out by General P. A. Dannenberg. On October 11 (23), British and French ships dropped anchor on the Bosphorus. On November 18 (30), P.S. Nakhimov destroyed the Turkish fleet in the Sinop Bay. A separate Caucasian corps under the command of V.O.Bebutov stopped the offensive of the Ottoman army to Tiflis and, having transferred hostilities to Turkish territory, on November 19 (December 1) defeated it in a battle near Bashkadyklar (east of Kars). In response, the Anglo-French squadron entered the Black Sea on December 23, 1853 (January 4, 1854) to obstruct the operations of the Russian fleet. It consisted almost entirely of propeller driven steam ships; the Russians had only a small number of such ships at their disposal. The Black Sea Fleet, unable to resist the allies on equal terms, was forced to take refuge in the Sevastopol Bay.

The result of the war was the weakening of Russia's naval power and its influence in Europe and the Middle East. The positions of Great Britain and France in the Eastern Mediterranean have significantly strengthened; France has become the leading power on the European continent. At the same time, Austria, although it managed to oust Russia from the Balkans, lost its main ally in her person in the inevitable future clash with the Franco-Sardinian bloc; thus, the way was opened for the unification of Italy under the rule of the Savoy dynasty. As for the Ottoman Empire, its dependence on the Western powers increased even more.

The essence of the Eastern question... The Eastern question is the name accepted in literature for a group of contradictions and problems in the history of international relations in the last third of the 18th century. - early 1920s. The formulation of the Eastern question as one of the main foreign policy problems of Russia refers to the period of the Russian-Turkish war of 1768-1774.

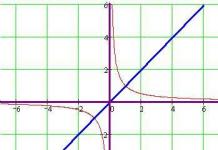

The Eastern question consisted of three main parts: Russia's relations with Turkey and the European powers (Great Britain, France, Austria, Prussia, etc.) over Turkish rule in the Balkans and the Black Sea straits; the status quo of the policy of Russia and other great powers in relation to the so-called contact zones (Greece, Serbia, Danube principalities), where the possessions of Turkey came in contact with the territorial or colonial possessions of the great powers; national and religious movements of non-Turkish peoples of the Ottoman Empire, who found support in different periods of Russia or other powers.

Russia's interest in resolving the Eastern question was caused primarily by the fact that it was a power with a wide access to the Black Sea. The security of its southern borders and the economic development of its steppe outskirts, which played a steadily increasing role in the economic life of the entire country, depended on one or another solution to the Eastern question. At the same time, in the Eastern question, the problem of the Bosphorus and Dardanelles straits was becoming increasingly stronger. On the one hand, Russia constantly and stubbornly sought a free exit for the Russian fleet from the Black Sea to the Mediterranean, and on the other, - to close the entrance to the Black Sea for the navies of other European powers. Both could be ensured only by the regime of the Black Sea straits that was beneficial for Russia. The establishment of such a regime was one of the urgent tasks of Russian diplomacy. The ideological substantiation of the Russian policy in the Eastern question was the idea of patronage of the Christian subjects of the Turkish Sultan - the Balkan Slavs, Greeks, Armenians. The patronage of these peoples was the constant trump card of Russian diplomacy in relations with Turkey.

A characteristic feature of the Eastern question for Russia was rather sharp political changes in the process of its solution. The periods of peaceful, allied relations between Russia and Turkey were unexpectedly replaced by a tense situation, which often turned into separate military clashes, and then into real wars. Then, as is usually the case in international practice, the next peace treaty between the powers followed; well, then everything was repeated again.

A large role in such a zigzag development of the Eastern question for Russia was played by the great Western powers, and above all England and France, which, firstly, had their own economic and political interests in the Middle East, and secondly, they did their best to prevent an increase in influence Russia in the Balkans, Turkey in the Black Sea straits. The need to constantly confront this anti-Russian policy of the Western powers kept the entire diplomatic service of Russia in unremitting tension both in St. Petersburg and abroad.

The Eastern question in the period under study is conventionally divided into two stages: the first - from the 1760s. before the Congress of Vienna in 1814-1815, the second - before the Paris Peace of 1856

Russian-Turkish relations at the beginning of the 19th century The beginning of the first stage of the solution of the Eastern question passed under the sign of the Russian-Turkish union treaty, concluded in January 1799 in Constantinople, that is, during the reign of Paul I. The treaty was opened new page in the history of Russian foreign policy. If earlier, as a result of the Russian-Turkish wars, the second half of XVIII v. Petersburg provided its merchant fleet with permanent access to the Black and Mediterranean Seas, but now Russia was the first of the great powers to receive the right of passage through the straits for its warships. At the same time, Russia, having gained a foothold in the Ionian Islands, acquired bases for military operations in the Mediterranean Sea. All this led to a huge increase in Russia's influence in the Eastern Mediterranean in the following years. In addition, Russia received and exercised the right to patronize the Orthodox population of the Ottoman Empire, the right to patronize Serbia and the Danube principalities. Turkey has recognized de facto Russia's interests in the North Caucasus and Transcaucasia.

In the first years of his reign, Alexander I supported the course of strengthening good-neighborly relations with Turkey. In 1805, a new union treaty was signed in Constantinople. He again proclaimed peace and good agreement between states. The parties guaranteed the integrity of their possessions and pledged to act jointly in all matters affecting security, as well as to provide each other with military assistance.

When creating anti-French coalitions, Turkey pledged to coordinate its actions with Russia and during the war to facilitate the passage of Russian warships through the straits. Agreements were reached to close the straits for foreign military ships and transport with military cargo. The contract was valid for nine years. These were very favorable conditions for Russia.

However, in reality, the union turned out to be short-lived. The Serbian uprising of 1804 marked the beginning of a broad national liberation movement in the Balkans and led to a crisis in Russian-Turkish relations. Serbian insurgent leaders turned to Russia for help. And although the union treaty did not allow the Russians to provide assistance to the rebels, in 1805, at the most difficult moment, Russian ships arrived in Galati and delivered weapons and ammunition to the Serbs.

Russian-Turkish war 1806-1812 Taking advantage of this fact, Napoleon managed to provoke a military conflict between Turkey and Russia. The Turkish Sultan ordered to close the straits for Russian ships. In December 1806, a new Russian-Turkish war broke out.

Starting it, Turkey hoped to return the Crimea, Transcaucasia to its possession, and also to strengthen the power of the Sultan in the Balkans. These aspirations were intensely fueled by French diplomacy.

During the war, the Russian authorities established close cooperation with Serbia. Money, ammunition, military instructors were sent to the Serbian rebels. Thanks to this, the Serbian army waged military operations in the Turkish rear in cooperation with the plans of the Russian command.

At the first stage, the Russian-Turkish war became protracted. The military operations were hesitant. The main forces were sent to capture and hold individual fortresses. Russian sailors were more active. Since the spring of 1807, the Mediterranean Sea has become the arena of major military operations of the Russian fleet. Vice-Admiral D.N. Senyavin occupied the island of Genedos and blockaded the Dardanelles. In the Dardanelles and Athos naval battles in July 1807, he defeated the Turkish fleet.

In March 1811 General M.I.Kutuzov was appointed commander of the Danube Army. In June, in a defensive battle near Ruschuk, he used a maneuver: he threw the Turkish army away from the fortress, after which he left it and took his army to the left bank of the Danube in order to lure the main enemy forces there and defeat them in the field. The Turkish commander Akhmet-bey succumbed to the military cunning of the Russian commander and sent up to 35 thousand of his fighters to the left bank of the Danube, leaving about 25 thousand in the camp near Ruschuk. Kutuzov with 20 thousand Russian troops blocked the Turkish forces crossing the Danube at Slobodzeya, and the 7-thousand-strong mobile detachment of General Markov, meanwhile, moved secretly to the Ruschuk camp of the Turks. On the night of October 1, this detachment crossed the Danube and a day later suddenly attacked the Turkish camp from the rear. The main forces of the enemy were cut off from their bases and surrounded. Suffering heavy losses from the fire of Russian artillery, the encircled group completely lost its combat effectiveness. Its remnants (numbering up to 12 thousand people) laid down their arms at the end of November. In October, the 35,000-strong group of Turks surrounded by Kutuzov on the left bank of the Danube was defeated, and in December General Kotlyarevsky, having made an unprecedented winter crossing with a small detachment through the ridges of the Lesser Caucasus, stormed the Turkish fortress of Akhalkalaki. The Turkish sultan realized that the war was lost.

Despite the tough opposition from France, on May 16, 1812, a peace treaty was signed between Russia and Turkey in Bucharest. According to the Bucharest Peace Treaty, Bessarabia with the fortresses Khotin, Bendery, Akkerman, Kiliya and Izmail retreated to Russia. The Russian-Turkish border was established along the Prut river before its connection with the Danube. Moldova and Wallachia returned to Turkey. Russia returned all the lands and fortresses taken from the battle in Asia. At the same time, for the first time, she received naval bases on the Caucasian coast of the Black Sea. Russia secured the autonomy of the Danube principalities, where it retained its influence. Serbia was granted internal autonomy. Russia received the right of merchant shipping along the entire course of the Danube, and military - to the mouth of the Prut.

But the main gain for Russia from the Bucharest Peace, of course, was that it removed Turkey from the accounts as an enemy of Russia at the most critical moment - literally on the eve of Napoleon's invasion and throughout the war of 1812.This allowed Alexander I to concentrate all his forces exclusively on repelling the invasion enemy from the west. No wonder, having learned about the conclusion of the Bucharest Peace, Napoleon was furious and unleashed a hail of reproaches on the Sultan and his ministers.

On the whole, the first stage of solving the Eastern question for Russia, apparently, ended with a positive result. She managed to significantly increase her influence in the Balkans, to achieve free passage of her ships through the Black Sea straits, and also to secure her southern borders and steppe outskirts.

Russian-Turkish war of 1828-1829 Adrianople peace. The second stage in solving the Eastern question for Russia (1816-1856), like the first, was characterized by rather sharp changes in relations between Russia and Turkey: the relatively peaceful, union times were unexpectedly replaced by years of tense, crisis situation, which, as a rule, , in armed conflicts and even in wars.

The first crisis in relations between Russia and Turkey at the second stage of the Eastern question arose in connection with the uprising in Greece in 1821 against Turkish rule. The Greeks, demanding autonomy from Turkey, turned to Russia for help as a Christian power. Alexander I hesitated. A personally convinced opponent of any uprisings and revolutions, he was also bound by the decision of the "Holy Alliance" to preserve the existing regimes. The Greeks were offended by the refusal to help. The advanced part of Russian society was disappointed. The Turkish government brutally suppressed the Greek uprising, and this made the problem of Greece even more aggravated. Turkey believed that the events in Greece were provoked by Russian agents.

Nicholas I made an attempt to solve the Greek problem by diplomatic means, involving the leading European powers. In June 1827, Russia, England and France signed a convention in London on the formation of an autonomous Greek state. However, Turkey categorically refused to accept it.

Turkey's refusal prompted the Allied powers to put military pressure on it. A united Anglo-Russian-French squadron was sent to the shores of the Peloponnese. On October 8, 1827, in the Navarino Bay, naval battle... As a result, the Turkish-Egyptian fleet was destroyed. The decisive role in the victory was played by the Russian squadron of L.P. Heiden.

But even after the defeat in the Navarino Bay, Turkey did not make concessions to the allies. Then the envoys of Russia, England and France left Constantinople. The Porta declared Russia an implacable enemy of Turkey and all Muslims. Russian subjects were expelled from Turkish possessions, and the Bosphorus and Dardanelles straits were closed to Russian ships. In April 1828, the manifesto of Nicholas I about the beginning of the war with Turkey was promulgated in St. Petersburg.

After the conclusion of a peace treaty with Iran, the Russian government transferred part of its troops from the Caucasus to the Black Sea-Balkan section of the border. The Russian troops in this war were led by Adjutant General P.H. Wittgenstein, then General N.I.Dibich.

On April 25, 1828, the Russian army entered the Danube principalities and began a rapid advance towards Constantinople. But by the fall, this progress had slowed down. The siege of Varna became protracted, and the situation was complicated by poor food supplies and illness in the army.

Diebitsch set out to conquer Silistria. By the summer of 1829, this fortress had finally surrendered. During the summer campaign, Russian troops crossed the Balkan Range, took Adrianople, the second capital of the Ottoman Empire. These defeats forced Turkey to negotiate peace. On September 2, 1829, a peace treaty was signed between Russia and Turkey in Adrianople.

According to the Peace of Adrianople, Greece received autonomy (a year later it declared its independence from Turkey). The rights of the Danube principalities (Moldova and Wallachia) in the sphere of self-government were confirmed and expanded. Serbia's autonomy was also confirmed. Russian merchants received the right to free trade throughout the Ottoman Empire. The Black Sea straits were declared open to merchant ships. Turkey returned all the territories occupied by Russian troops in the European theater of military operations, with the exception of the Danube estuary with the islands. The border passed, as before, along the Prut river.

As a result of the Adrianople Peace, Russia's influence in the Balkans increased significantly. This treaty in the aggregate of articles was in effect until the Paris Peace of 1856. Separate articles of the Adrianople peace found development in the Unkar-Iskelesi Treaty of 1833, the London Conventions of 1840 and 1841. on the international status of the Black Sea straits.

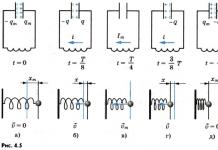

Eastern question in the 30-40s. The Unkar-Iskelesi Treaty of Friendship and Mutual Assistance between Russia and Turkey confirmed the inviolability of the terms of the Adrianople Peace and all previously concluded Russian-Turkish treaties. Russia pledged to provide Turkey with the necessary assistance with its sea and ground forces... According to the secret article, Turkey was supposed to close the passage through the Dardanelles for all foreign warships. This was the main point of the agreement.

The closure of the Dardanelles to the navies of the non-Black Sea powers ensured the security of Russia's southern borders, and the principle of joint defense of the Black Sea straits allowed it to reliably close the access of enemy forces to them, even in the event of war.

The conclusion of the Unkar-Iskelesi treaty was a major victory for Russian diplomacy, the significance of which was also emphasized by the fact that it was achieved without a single shot being fired. This served as proof of the strength and influence of Russia in the Middle East.

Subsequently, however, Russia gradually began to lose its influence in the Eastern question. According to the London Convention, signed in 1840 by England, Prussia, Austria and Russia, it was established that the principle of closing the Black Sea straits for foreign warships would be observed only as long as Turkey was in peace. Thus, any power hostile to Russia, having entered into an alliance with Turkey, could enter its navy into the Black Sea. The Second London Convention, signed in 1841 by representatives of five powers (including France), confirmed the principle of neutralizing the straits. The Russian fleet was trapped in the Black Sea.

With the conclusion of the London Conventions and hesitation in the policy of "preserving a weak neighbor", Russia has sharply weakened its positions in the Balkans and the Middle East. The fact that Russia had missed the Black Sea privileges hurt the ambitions of the country's top leadership, forcing them to seek revenge.

Crimean War... Crimean War of 1853-1856 was, as it were, the final chord in Russia's attempts to resolve the Eastern question at its second stage.

The reason for the war was the religious conflict between the Catholic and Orthodox clergy over the holy places in Palestine. Such conflicts have arisen more than once. But in this case, the Turkish sultan, who ruled Palestine, under pressure from the French government decided the dispute in favor of the Catholics. Russia came out in defense of the local Orthodox clergy.

The religious dispute soon escalated into a diplomatic conflict, which became an external manifestation of acute contradictions between the European powers in the Middle East. This region found itself in the zone of economic and military-strategic interests, mainly of England, France and Russia.

The British and French bourgeoisie, taking advantage of the weakening of the Turkish Sultanate, intensively mastered the Middle East markets. Russia was their main competitor in this region. The Western powers sought by any means to weaken Russia's influence in the Balkans and the Middle East, in order to thereby strengthen their political, economic and military-strategic positions here.

The government of Nicholas I really faced the threat of international isolation, however, it was not realized in time. Prince A.S. Menshikov was sent to Constantinople as ambassador extraordinary. He demanded that the Sultan not only restore privileges Orthodox Church in Palestine, but also to recognize a Russian protectorate over the Orthodox subjects of Turkey. Nicholas I counted on the friendly neutrality of England and the support of Prussia and Austria.

These hopes did not come true. England and France intervened in the Russian-Turkish conflict on the side of the Sultan, while Austria and Prussia took neutrality, which was undesirable for Russia.

The Sultan agreed to satisfy Russia's demands regarding the privileges of the Orthodox clergy in Palestine, but refused to recognize the protectorate of the Russian emperor over the Orthodox subjects of Turkey. In June 1853 Nicholas I ordered the Russian army to cross the Prut and occupy the Danube principalities - Moldavia and Wallachia. After that, the squadrons of Turkey's allies, violating the 1841 convention on the neutrality of the Black Sea straits, entered the Sea of Marmara. Four days later, the Sultan, prompted by Western diplomats, in an ultimatum demanded the withdrawal of Russian troops. Having not received the desired answer from St. Petersburg, in October 1853 he began military operations on the Danube and in the Transcaucasus. England and France declared Russia the aggressor.

The Crimean War had two stages: the first - the Russian-Turkish campaign on the Danube Front (October 1853 - April 1854) and the second - the landing of the British and French troops in the Crimea and the defense of Sevastopol (April 1854 - February 1856).

At the first stage, the Danube territories became the main theater of military operations of the Turkish and Russian armies. Despite the numerical superiority of the Turks, the Russian troops managed to win a number of battles - near the village of Chetati (January 1854) and a sea battle in the Sinop Bay. The Russian squadron was commanded by Vice Admiral P.S. Nakhimov, a talented officer of the Black Sea Fleet who was loved by sailors.

After Sinop and the hostilities on the Danube, the governments of England and France realized that Turkey would not be able to withstand single combat with Russia on its own. This prompted them to intervene in the course of hostilities.

This was preceded by an active propaganda campaign. In the press and in speeches, Russia was accused of an aggressive policy, demands were made to defend Turkey. In March 1854, the governments of the Western powers presented to the Russian emperor a demand for the withdrawal of Russian troops from Turkish territories. Queen Victoria of England and French Emperor Napoleon III declared war on Russia. True, it was not possible to create a coalition of the European countries of England and France. A year later, only the Kingdom of Sardinia joined them.

Fearing Austria's entry into the war, Nicholas I decided to withdraw his troops from Wallachia and Moldavia. It would seem that the Allies' demand was satisfied, but the war continued. She entered a new stage. Now against Russia was not only Turkey, but the allied block England-France-Turkey.

A detailed plan for the conduct of the war was developed in Paris. It meant large-scale military operations on the Danube, in the Transcaucasus, in the Baltic and White Seas and in the Kamchatka region. But the Crimea was the main theater of the war.

Having not achieved serious success in Far East and in the North, England and France in the fall of 1854 decided to strike at the main strategic base Black Sea Fleet- Sevastopol. To capture it on the Bulgarian coast, in the region of Varna, the Allies concentrated a large expeditionary army, which they later landed in the Crimea. The English and French strategists were counting on a quick victory. But their landing operation turned into a protracted, exhausting struggle, which went down in history under the name "Defense of Sevastopol".

The Allied landing force included 360 different ships and a 62,000-strong army with siege weapons. From the total western naval forces 31 ships made up a combat squadron, which significantly surpassed the entire fleet located in Sevastopol under the command of Admiral P.S. Nakhimov. The Sevastopol fortress had a fairly well-fortified coastline, but was almost never fortified from land. And this was known to the opponents. Taking this information into account, a plan was developed to capture the fortress.

On the entire Crimean peninsula there were about 52 thousand Russian troops. However, some of them were stationed in the eastern part of Crimea. The Sevastopol army under the leadership of A.S. Menshikov consisted of 33 thousand soldiers with 96 guns.

After the landing of the enemy troops, Menshikov made an attempt to stop him at the turn of the Alma River. Here on September 8 the first battle of Russian troops with the interventionists took place. The Russian army was defeated and suffered heavy losses. The Russians lost 6 thousand people in this battle, the allies - 3 thousand. The technical backwardness of Russia manifested itself in human losses. Menshikov led the army first to Sevastopol, and then, fearing to lose contact with the inner provinces, to Bakhchisarai.

However, under the impression of a stubborn battle on the Alma, the Anglo-French military leadership abandoned the intention to attack Sevastopol from the north. The allies bypassed the Sevastopol Bay and began to prepare a naval base in Balaklava. From here began their attack on the Sevastopol fortifications from the south.

The defenders of Sevastopol received the necessary time to prepare the city for defense. Day and night, under the leadership of the military engineer E.I. Totleben, the construction of ground bastions, trenches and other fortifications went on. On the hills around the city on the south side, seven bastions arose, interconnected by redoubts, batteries, or simply trenches.

The crews of the ships went over to land and took up defensive positions. These days, 10 thousand sailors went ashore, and in total during the defense - 20 thousand. They were the decisive force in the defense of the city. The ship's guns were brought ashore and installed on the bastions. To prevent the enemy fleet from entering the bay, seven old sailing ships were sunk at the entrance to it. The enemy fleet could no longer shell the city.

The main heroes and the soul of the defense were the naval commanders - Vice-Admiral V.A.Kornilov and Admiral P.S.Nakhimov.

On September 25, 1854, by order of the garrison, the city was declared a state of siege. This date went down in history as the first day of heroic defense. In total, the siege of Sevastopol lasted 349 days.

It was incredibly heavy. The defenders were in dire need of food, ammunition, and drinking water. The garrison suffered huge losses. The first detachment of sisters of mercy in Russian history took part in the defense of Sevastopol. It was formed in St. Petersburg from female volunteers. Under the leadership of doctors and surgeon N.I. Pirogov, they carried a grueling and noble watch in hospitals and at dressing stations.

The defense of Sevastopol throughout its entire length was distinguished by the high combat activity of its defenders. They became especially famous for their bold and daring night outings.

Fighting off enemy attacks, the defenders of the city continued to build new batteries and bastions, deepened ditches, and erected new redoubts. By order of Nakhimov, a floating bridge was erected across the Yuzhnaya Bay. This helped speed up the transfer of reinforcements and the supply of ammunition.

However, over time, the superiority of the enemy over the besieged became more and more tangible. The ranks of the defenders of Sevastopol were melting. In August 1855, a floating bridge was built across the Big Bay to withdraw troops from the southern side of the city to the North.

The Crimean campaign ended, but not the way the governments of England and France would like. The defense of Sevastopol fettered the huge forces of the allies and dragged out the war.

Towards the end of 1855 England and France began to lean towards peace negotiations. Peace was needed on both sides. The Paris Peace Congress opened in February 1856. Representatives from Russia, England, France, Turkey, Sardinia, Austria and Prussia took part in it. Russian diplomats, using the contradictions between the winners, and with some rapprochement with France, were able to achieve a softening of the peace conditions. But all the same, the Paris Peace Treaty was very difficult for Russia.

He proclaimed the restoration of peace between the participants in the war and envisaged: the return by Russia of Turkey of the city of Kars with a fortress in exchange for Sevastopol and other cities in the Crimea, occupied by Turkey's allies; declaring the Black Sea neutral, that is, open to merchant ships of all nations, with the prohibition of Russia and Turkey to have navies and arsenals there; the abolition of Russia's right to "speak in favor" of the principalities in Moldavia and Wallachia. Serbia, Moldavia and Wallachia were given over to the protection of European states. It was a hard and humiliating defeat for Russia.

The war revealed the economic backwardness of Russia. The serfdom system slowed down the industrial development of the country, negatively affected the military potential. The recruiting system of army formation has long been rejected in the West. The maintenance of an army of more than a million people was costly for the state. Army formations were scattered throughout the empire. In the absence of a developed network of railways in the Russian off-road conditions, their rapid transfer to solve military-strategic tasks was difficult.

A serious lag in Russian industry was also manifested in the field of arming the army. The Russian artillery, which became so famous in the war of 1812, was now noticeably inferior to the English and French ones. The Russian fleet continued to be predominantly sailing. In the Black Sea squadron, out of 21 large warships, only 7 were steam ships, while the Anglo-French fleet consisted almost entirely of steam ships with screw engines.

The defeat in the Crimean War and the difficult conditions of the Paris Peace caused sharp criticism in Russia of the domestic and foreign policy of Nicholas I. It was felt that the country was on the verge of important changes in socio-economic and socio-political life.

The "Eastern question" as a concept arose at the end of the 18th century, but as a diplomatic term it began to be used from the 30s of the 19th century. It owes its birth to three factors at once: the decline of the once powerful Ottoman state, the growth of the liberation movement directed against Turkish enslavement, and the aggravation of contradictions between European countries for domination in the Middle East.

In addition to the great European powers, Egypt, Syria, part of the Transcaucasus, etc. were involved in the "Eastern question".

In the late 18th century, the once terrifying Turks fell into disrepair. Most of all, this was beneficial to Austria, which managed to penetrate the Balkans through Hungary, and Russia, which expanded its borders to the Black Sea in the hope of reaching the Mediterranean shores.

It all began with the uprising of the Greeks in the 20s of the 19th century. It was this event that prompted the West to act. After the Turkish sultan's refusal to accept the independence of the Hellenes, an alliance of Russian, British and French troops destroyed the Turkish and Egyptian naval flotillas. As a result, Greece freed itself from the Turkish yoke, and Moldova, Serbia and Wallachia - the Balkan provinces of the Ottoman Empire - received autonomy, albeit within it.

In the 30s of the same century, all the Middle Eastern possessions of Ottoman Turkey were already involved in the already ripe "Eastern question": Egypt conquered Syria from its suzerain, and only the intervention of England helped to return it.

At the same time, another problem arose: the right to cross the Bosphorus, which was controlled by the Turks. According to the Convention, no warship of another state had the right to pass through these narrow passages if Turkey was in a state of peace.

This was contrary to the interests of Russia. The "Eastern question" in the 19th century took a different turn for Russia after it acted as an ally of the Turks in the war against the Egyptian Pasha. Against the background of the defeat of the Ottoman army, the king brought his squadron into the Bosphorus and landed numerous troops, ostensibly to protect Istanbul.

As a result, an agreement was concluded according to which only Russian warships could enter the Turkish straits.

Ten years later, in the early forties, the "Eastern question" became aggravated. Porta, which promised to improve the living conditions of the Christian part of its population, actually did nothing. And for the Balkan peoples there was only one way out: to start an armed struggle against the Ottoman yoke. And then he demanded from the Sultan the right to patronage over Orthodox subjects, but the Sultan refused. As a result, it began which ended in the defeat of the tsarist troops.

Despite the fact that Russia lost, the Russian-Turkish war became one of the decisive stages in the solution of the "Eastern question". The process of liberation of the South Slavic peoples began. Turkish rule in the Balkans received a fatal blow.

The "Eastern question", while playing an important role, had two main directions for it: the Caucasus and the Balkans.

Trying to expand his possessions in the Caucasus, the Russian tsar tried to ensure a secure connection with all the newly occupied territories.

At the same time, in the Balkans, the local population sought to provide assistance to Russian soldiers, whom the Ottoman troops offered stubborn resistance.

With the help of Serbian and Bulgarian volunteers, the tsarist troops took the city of Andrianople, thereby ending the war.

And in the Kara direction, a significant part was liberated, which became a significant event in the military campaign.

As a result, a treaty was signed stating that Russia receives enough large territory from the Black Sea part of the Caucasus, as well as many Armenian regions. The issue of Greek autonomy was also resolved.

Thus, Russia has fulfilled its mission in relation to the Armenian and Greek peoples.