The first year without war. For Soviet people it was different. This is a time of struggle against devastation, hunger and crime, but it is also a period of labor achievements, economic victories and new hopes.

Tests

In September 1945, the long-awaited peace came to Soviet soil. But it came at a high price. More than 27 million became victims of the war. people, 1,710 cities and 70 thousand villages were wiped off the face of the earth, 32 thousand enterprises, 65 thousand kilometers were destroyed railways, 98 thousand collective farms and 2890 machine and tractor stations. Direct damage to the Soviet economy amounted to 679 billion rubles. The national economy and heavy industry were set back at least ten years.

Hunger added to the enormous economic and human losses. It was facilitated by the drought of 1946, the collapse agriculture, a lack of labor and equipment, which led to a significant loss of crops, as well as a reduction in livestock numbers by 40%. The population had to survive: cook borscht from nettles or bake cakes from linden leaves and flowers.

Dystrophy became a common diagnosis in the first post-war year. For example, by the beginning of 1947, in the Voronezh region alone there were 250 thousand patients with a similar diagnosis, in total in the RSFSR - about 600 thousand. According to Dutch economist Michael Ellman, a total of 1 to 1.5 million people died from famine in the USSR in 1946-1947.

Historian Veniamin Zima believes that the state had sufficient grain reserves to prevent famine. Thus, the volume of exported grain in 1946-48 was 5.7 million tons, which is 2.1 million tons more than the exports of the pre-war years.

To help the starving people from China, the Soviet government purchased about 200 thousand tons of grain and soybeans. Ukraine and Belarus, as victims of war, received assistance through UN channels.

Stalin's miracle

The war had just ended, but no one canceled the next five-year plan. In March 1946, the fourth five-year plan for 1946-1952 was adopted. His goals are ambitious: not only to achieve the pre-war level of industrial and agricultural production, but also to surpass it.

Iron discipline reigned at Soviet enterprises, ensuring rapid production rates. Paramilitary methods were necessary to organize the work of diverse groups of workers: 2.5 million prisoners, 2 million prisoners of war and about 10 million demobilized.

Particular attention was paid to the restoration of Stalingrad, destroyed by the war. Molotov then declared that not a single German would leave the USSR until the city was completely restored. And, it must be said that the painstaking work of the Germans in construction and public utilities contributed to the appearance of Stalingrad, which rose from the ruins.

In 1946, the government adopted a plan to provide loans to the regions most affected by fascist occupation. This made it possible to quickly restore their infrastructure. The emphasis was on industrial development. Already in 1946, industrial mechanization was 15% of the pre-war level, a couple more years and the pre-war level will be doubled.

Everything for the people

The post-war devastation did not prevent the government from providing citizens with comprehensive support. On August 25, 1946, by resolution of the Council of Ministers of the USSR, the population was issued a mortgage loan at 1% per annum as assistance in solving the housing problem.

“To provide workers, engineers and employees with the opportunity to purchase ownership of a residential building, oblige the Central Communal Bank to issue a loan in the amount of 8-10 thousand rubles. those buying a two-room residential building with a repayment period of 10 years and 10-12 thousand rubles. buying a three-room residential house with a repayment period of 12 years,” the resolution said.

Doctor of Technical Sciences Anatoly Torgashev witnessed those difficult post-war years. He notes that, despite various kinds of economic problems, already in 1946 at enterprises and construction sites in the Urals, Siberia and Far East managed to raise workers' wages by 20%. The official salaries of citizens with secondary and higher specialized education were increased by the same amount.

Persons with various academic degrees and titles received serious increases. For example, the salaries of a professor and a doctor of sciences increased from 1,600 to 5,000 rubles, an associate professor and a candidate of sciences - from 1,200 to 3,200 rubles, and a university rector - from 2,500 to 8,000 rubles. It is interesting that Stalin, as Chairman of the Council of Ministers of the USSR, had a salary of 10,000 rubles.

But for comparison, the prices for the main products of the food basket for 1947. Black bread (loaf) – 3 rubles, milk (1 l) – 3 rubles, eggs (a dozen) – 12 rubles, vegetable oil (1 l) – 30 rubles. A pair of shoes could be bought for an average of 260 rubles.

Repatriates

After the end of the war, over 5 million Soviet citizens found themselves outside their country: over 3 million in the zone of action of the Allies and less than 2 million in the zone of influence of the USSR. Most of them were Ostarbeiters, the rest (about 1.7 million) were prisoners of war, collaborators and refugees. At the Yalta Conference of 1945, the leaders of the victorious countries decided on the repatriation of Soviet citizens, which was to be mandatory.

By August 1, 1946, 3,322,053 repatriates had been sent to their place of residence. The report of the command of the NKVD troops noted: “The political mood of the repatriated Soviet citizens is overwhelmingly healthy, characterized by a great desire to come home as soon as possible - to the USSR. There was everywhere a significant interest and desire to find out what was new in life in the USSR, and to quickly take part in the work to eliminate the destruction caused by the war and strengthen the economy of the Soviet state.”

Not everyone received the returnees favorably. The resolution of the Central Committee of the All-Union Communist Party of Bolsheviks “On the organization of political and educational work with repatriated Soviet citizens” stated: “Individual party and Soviet workers took the path of indiscriminate distrust of repatriated Soviet citizens.” The government reminded that “returnees Soviet citizens have regained all their rights and must be involved in active participation in labor and social and political life.”

A significant part of those who returned to their homeland were thrown into areas involving heavy physical labor: in the coal industry of the eastern and western regions (116 thousand), in the ferrous metallurgy (47 thousand) and timber industry (12 thousand). Many of the repatriates were forced to enter into permanent employment agreements.

Banditry

One of the most painful problems of the first post-war years for the Soviet state was the high crime rate. The fight against robbery and banditry has become a headache for Sergei Kruglov, the Minister of Internal Affairs. The peak of crimes occurred in 1946, during which more than 36 thousand armed robberies and over 12 thousand cases of social banditry were identified.

Post-war Soviet society was dominated by a pathological fear of rampant crime. Historian Elena Zubkova explained: “People’s fear of the criminal world was based not so much on reliable information, but rather came from its lack and dependence on rumors.”

Crash social order, especially in the territories of Eastern Europe ceded to the USSR, was one of the main factors provoking a surge in crime. About 60% of all crimes in the country were committed in Ukraine and the Baltic states, with the highest concentration noted in the territories of Western Ukraine and Lithuania.

The seriousness of the problem with post-war crime is evidenced by a report classified “top secret” received by Lavrentiy Beria at the end of November 1946. It, in particular, contained 1,232 references to criminal banditry, taken from private correspondence of citizens in the period from October 16 to November 15, 1946.

Here is an excerpt from a letter from a Saratov worker: “Since the beginning of autumn, Saratov is literally terrorized by thieves and murderers. They strip people in the streets, rip their watches off their hands, and this happens every day. Life in the city simply stops when darkness falls. Residents have learned to walk only in the middle of the street, not on the sidewalks, and look suspiciously at anyone who approaches them.”

Nevertheless, the fight against crime has borne fruit. According to reports from the Ministry of Internal Affairs, during the period from January 1, 1945 to December 1, 1946, 3,757 anti-Soviet formations and organized gangs, as well as 3,861 gangs associated with them, were liquidated. Almost 210 thousand bandits, members of anti-Soviet nationalist organizations, their henchmen and other anti-Soviet elements were destroyed . Since 1947, the crime rate in the USSR has declined.

Despite the fact that the USSR suffered very heavy losses during the war, it entered the international arena not only not weakened, but became even stronger than before. In 1946-1948. In the countries of Eastern Europe and Asia, communist governments came to power and set a course for building socialism along the Soviet model.

However, the leading Western powers pursued a power policy towards the USSR and socialist states. One of the main means of containing them was atomic weapons, which the United States enjoyed a monopoly on. Therefore the creation atomic bomb became one of the main goals of the USSR. This work was led by a physicist I. V. Kurchatov. The Institute was created atomic energy and the Institute of Nuclear Problems of the USSR Academy of Sciences. In 1948, the first atomic reactor was launched, and in 1949, the first atomic bomb was tested at the test site near Semipalatinsk. Individual Western scientists secretly helped the USSR work on it. Thus, a second nuclear power appeared in the world, and the US monopoly on nuclear weapons ended. Since that time, the confrontation between the USA and the USSR has largely determined the international situation.

Economic recovery.

Material losses in the war were very great. The USSR lost a third of its national wealth in the war. Agriculture was in deep crisis. The majority of the population was in distress; its supplies were carried out using a rationing system.

In 1946, the Five-Year Reconstruction and Development Plan Act was passed national economy. It was necessary to speed up technical progress, strengthen the country's defense power. Post-war five year plan marked by large construction projects (hydroelectric power stations, state district power stations) and the development of road and transport construction. Technical re-equipment of industry Soviet Union facilitated the removal of equipment from German and Japanese enterprises. The highest rates of development have been achieved in such industries as ferrous metallurgy, oil and coal mining, and construction of machinery and machine tools.

After the war, the village found itself in a more difficult situation than the city. Collective farms carried out strict measures to procure bread. If earlier collective farmers gave only part of the grain “to the common barn,” now they were often forced to give all the grain. Discontent in the countryside grew. The area under cultivation has been greatly reduced. Due to worn-out equipment and a lack of workers, field work was carried out late, which negatively affected the harvest.

Main features of post-war life.

A significant part of the housing stock was destroyed. The problem of labor resources was acute: immediately after the war, many demobilized people returned to the city, but the enterprises still did not have enough workers. We had to recruit workers in the villages, among vocational school students.

Even before the war, decrees were adopted, and after it continued to be in force, according to which workers were prohibited from leaving enterprises without permission under pain of criminal punishment.

To stabilize financial system in 1947, the Soviet government carried out a monetary reform. Old money was exchanged for new money in a ratio of 10:1. After the exchange, the amount of money among the population decreased sharply. At the same time, the government has reduced prices for consumer products many times. The card system was abolished, food and industrial goods appeared on open sale at retail prices. In most cases, these prices were higher than ration prices, but significantly lower than commercial ones. The abolition of cards improved the situation of the urban population.

One of the main features post-war life became the legalization of the activities of the Russian Orthodox Church. In July 1948, the church celebrated the 500th anniversary of self-government, and in honor of this, a meeting of representatives of local Orthodox churches was held in Moscow.

Power after the war.

With the transition to peaceful construction, structural changes occurred in the government. In September 1945, the State Defense Committee was abolished. On March 15, 1946, the Council of People's Commissars and the People's Commissariats were renamed the Council of Ministers and Ministries.

In March 1946, the Bureau of the Council of Ministers was created, the chairman of which was L. P. Beria . He was also tasked with monitoring the work of internal affairs and state security agencies. He occupied quite a strong position in the leadership A.A. Zhdanov, combining the duties of a member of the Politburo, the Organizing Bureau and party secretary, but he died in 1948. At the same time, the positions of G.M. Malenkova, who previously occupied a very modest position in the governing bodies.

Changes in party structures were reflected in the program of the 19th Party Congress. At this congress, the party received a new name - instead of the All-Union Communist Party (Bolsheviks) it began to be called Communist Party Council and Union (CPSU).

USSR in the 50s and early 60s. XX century

Changes after the death of Stalin and the XX Congress of the CPSU.

Stalin died on March 5, 1953. The leader’s closest associates proclaimed a course towards establishing collective leadership, but in reality a struggle for leadership unfolded between them. Minister of Internal Affairs Marshal L.P. Beria initiated an amnesty for prisoners whose sentence was no more than five years. He put his supporters at the head of several republics. Beria also proposed softening the policy towards collective farms and advocated easing international tensions and improving relations with Western countries.

However, in the summer of 1953, other members of the top party leadership, with the support of the military, organized a conspiracy and overthrew Beria. He was shot. The fight didn't end there. Malenkov, Kaganovich and Molotov were gradually removed from power, and G.K. Zhukov was removed from the post of Minister of Defense. Almost all of this was done on the initiative N.S. Khrushchev, who since 1958 began to combine party and government posts.

In February 1956, the 20th Congress of the CPSU took place, the agenda of which included an analysis of the international and domestic situation and summing up the results of the fifth five-year plan. At the congress, the issue of exposing Stalin's personality cult was raised. The report “On the cult of personality and its consequences” was made by N.S. Khrushchev. He spoke about Stalin's numerous violations of Lenin's policies, about "illegal methods of investigation" and purges that killed many innocent people. They talked about Stalin's mistakes as statesman(for example, a miscalculation in determining the date of the start of the Great Patriotic War). Khrushchev’s report after the congress was read out across the country at party and Komsomol meetings. Its content shocked the Soviet people, many began to doubt the correctness of the path that the country had been following since October Revolution .

The process of de-Stalinization of society took place gradually. On Khrushchev’s initiative, cultural figures were given the opportunity to create their works without total censorship control and strict party dictate. This policy was called the “thaw” after the name of the then popular novel by the writer I. Ehrenburg.

During the “thaw” period, significant changes occurred in culture. Works of literature and art have become deeper and more sincere.

Economic reforms. Development of the national economy.

Reforms carried out in the 50s - early 60s. XX century, were of a contradictory nature. At one time, Stalin outlined the economic milestones that the country was supposed to reach in the near future. Under Khrushchev, the USSR reached these milestones, but in the changed conditions, their achievement did not have such a significant effect.

The strengthening of the national economy of the USSR began with changes in the commodity sector. It was decided to establish reasonable prices for agricultural products and change tax policy so that collective farmers would have a financial interest in selling their products. In the future, it was planned to increase the cash income of collective farms, pensions, and ease the passport regime.

In 1954, on Khrushchev’s initiative, it began development of virgin lands. Later they began to reorganize the economic structure of collective farmers. Khrushchev proposed building urban-type buildings for rural residents and taking other measures to improve their lives. Easing the passport regime has opened the floodgates for migration rural population to the city. Various programs were adopted to increase the efficiency of agriculture, and Khrushchev often saw a panacea in the cultivation of any one crop. The most famous was his attempt to turn corn into the “queen of the fields.” The desire to grow it regardless of the climate caused damage to agriculture, and Khrushchev received the nickname “corn grower” among the people.

50s XX century are characterized by great successes in industry. The output of heavy industry increased especially. Much attention was paid to those industries that ensured the development of technology. The program of complete electrification of the country was of paramount importance. New hydroelectric power stations and state district power stations were put into operation.

The impressive successes of the economy gave the leadership led by Khrushchev confidence in the possibility of even further accelerating the pace of development of the country. The thesis was put forward about the complete and final construction of socialism in the USSR, and in the early 60s. XX century set course for construction communism , that is, a society where every person can satisfy all their needs. According to the document adopted in 1962 XXII Congress The CPSU's new party program was supposed to complete the construction of communism by 1980. However, the serious difficulties in the economy that began at the same time clearly demonstrated to the citizens of the USSR the utopianism and adventurism of Khrushchev's ideas.

Difficulties in industrial development were largely due to ill-conceived reorganizations recent years Khrushchev's reign. Thus, most of the central industrial ministries were liquidated, and the management of the economy passed into the hands of economic councils, created in certain regions of the country. This innovation led to a breakdown in ties between regions and slowed down the introduction of new technologies.

Social sphere.

The government has carried out a number of measures to improve the well-being of the people. A law on state pensions was introduced. Tuition fees have been abolished in secondary and higher educational institutions. Heavy industry workers were put on shorter working hours without reducing their wages. The population received various cash benefits. The material incomes of workers have increased. Simultaneously with the increase in wages, prices for consumer goods were reduced: certain types of fabric, clothing, goods for children, watches, medicines, etc.

Many public funds were also created that paid various preferential benefits. Thanks to these funds, many were able to study at school or university. The working day was reduced to 6-7 hours, and on holidays and holidays the working day lasted even shorter. Working week became shorter by 2 hours. On October 1, 1962, all taxes on wages of workers and employees were abolished. Since the late 50s. XX century The sale of durable goods on credit began.

Undoubted successes in the social sphere in the early 60s. XX century were accompanied by negative phenomena, especially painful for the population: essential products, including bread, disappeared from store shelves. There were several protests by workers, the most famous of which was the demonstration in Novocherkassk, which was suppressed by troops using weapons, which led to many casualties.

Foreign policy of the USSR in 1953-1964.

Foreign policy was characterized by the struggle to strengthen the position of the USSR and international security.

The settlement of the Austrian question was of great international importance. In 1955, on the initiative of the USSR, a State Treaty with Austria was signed in Vienna. Were also installed diplomatic relations with Germany, Japan.

Soviet diplomacy actively sought to establish a wide variety of ties with all states. A severe test was the Hungarian uprising of 1956, which was suppressed Soviet troops. Almost simultaneously with the Hungarian events in 1956, arose Suez crisis .

On August 5, 1963, an Agreement was concluded in Moscow between the USSR, the USA and Great Britain banning nuclear tests on land, in the air and at sea.

Relations with most socialist countries had long been streamlined - they clearly obeyed the instructions of Moscow. In May 1953, the USSR restored relations with Yugoslavia. The Soviet-Yugoslav declaration was signed, which proclaimed the principle of the indivisibility of the world, non-interference in internal affairs, etc.

The main foreign policy theses of the CPSU were criticized by the Chinese communists. They also disputed the political assessment of Stalin's activities. In 1963-1965. The PRC made claims to a number of border territories of the USSR, and an open struggle broke out between the two powers.

The USSR actively cooperated with the countries of Asia and Africa that won independence. Moscow helped developing countries create national economies. In February 1955, a Soviet-Indian agreement was signed on the construction of a metallurgical plant in India with the help of the USSR. The USSR provided assistance to the United Arab Republic, Afghanistan, Indonesia, Cambodia, Syria and other countries in Asia and Africa.

USSR in the second half of the 60s - early 80s. XX century

The overthrow of N.S. Khrushchev and the search for a political course.

Development of science, technology and education.

In the USSR the number has increased scientific institutions and scientific workers. Each union republic had its own Academy of Sciences, under which was the whole system scientific institutions. Significant progress has been made in the development of science. On October 4, 1957, the world's first artificial Earth satellite was launched, then spacecraft reached the moon. On April 12, 1961, the first manned space flight in history took place. The first ascent of the CSM of space became Yu.L. Gagarin.

New and increasingly powerful power plants were built. Aircraft manufacturing developed successfully, nuclear physics, astrophysics and other sciences. Many cities created scientific centers. For example, in 1957, Akademgorodok was built near Novosibirsk.

After the war, the number of schools decreased catastrophically; one of the government’s tasks was to create new secondary schools. educational institutions. The increase in the number of high school graduates has led to an increase in the number of university students.

In 1954, coeducational education for boys and girls was restored in schools. Tuition fees for high school students and students were also abolished. Students began to receive stipends. In 1958, compulsory eight-year education was introduced, and the ten-year school was transferred to 11-year education. Soon in curriculum schools included labor in production.

Spiritual life and culture of “developed socialism”.

The ideologists of the CPSU sought to quickly forget Khrushchev’s idea of building communism by 1980. This idea was replaced by the slogan of “developed socialism.” It was believed that under “developed socialism” nations and nationalities were coming closer together, a single community had emerged - Soviet people. They talked about the rapid development of the country's productive forces, about blurring the lines between city and countryside, about the distribution of wealth on the principles “From each according to his abilities, to each according to his work.” Finally, the transformation of the state of the dictatorship of the proletariat into a nation-wide state of workers, peasants and the people's intelligentsia, between whom the lines were also continuously erased, was proclaimed.

In the 60-70s. XX century culture has ceased to be synonymous with ideology, its uniformity has been lost. The ideological component of culture receded into the background, giving way to simplicity and sincerity. Works created in the provinces - in Irkutsk, Kursk, Voronezh, Omsk, etc. - gained popularity. Culture was given a special status.

Nevertheless, ideological trends in culture were still very strong. Negative role militant atheism played. The persecution of the Russian intensified Orthodox Church. Temples across the country were closed, priests were removed and defrocked. Militant atheists created special organizations to preach atheism.

Great Patriotic War, which became a difficult test and shock for the Soviet people, turned upside down the entire way of life and the course of life of the majority of the country's population for a long time. Enormous difficulties and material deprivations were perceived as temporarily inevitable problems, as a consequence of the war.

The post-war years began with the pathos of restoration and hopes for change. The main thing is that the war was over, people were happy that they were alive, everything else, including living conditions, was not so important.

All the difficulties of everyday life fell mainly on the shoulders of women. Among the ruins of destroyed cities, they planted vegetable gardens, cleared rubble and cleared places for new construction, while raising children and providing for their families. People lived in the hope that a new, freer and more prosperous life would come very soon, which is why Soviet society of those years is called the “society of hopes.”

"Second Bread"

The basic reality of everyday life of that time, trailing like a trail from war era, - constant lack of food, half-starved existence. The most important thing was missing - bread. Potatoes became the “second bread”; its consumption doubled; it primarily saved villagers from hunger.

Flatbreads were baked from grated raw potatoes rolled in flour or breadcrumbs. They even used frozen potatoes that were left in the field for the winter. They took it out of the ground, peeled it off and added a little flour, herbs, salt (if any) to this starchy mass and fried the cakes. This is what collective farmer Nikiforova from the village of Chernushki wrote in December 1948:

“The food is potato, sometimes with milk. In the village of Kopytova they bake bread like this: they grind a bucket of potatoes and put in a handful of flour for gluing. This bread contains almost no protein necessary for the body. It is absolutely necessary to establish a minimum amount of bread that must be left untouched, at least 300 g of flour per person per day. Potatoes are a deceptive food, more flavorful than filling.”

People of the post-war generation still remember how they waited for spring, when the first grass would appear: you can cook empty cabbage soup from sorrel and nettle. They also ate “pestyshi” - shoots of young horsetail, and “pillars” - flower stalks of sorrel. Even vegetable peelings were pounded in a mortar, and then boiled and used for food.

Here is a fragment from an anonymous letter to I.V. Stalin dated February 24, 1947: “Collective farmers mainly eat potatoes, and many don’t even have potatoes, they eat food waste and hope for spring, when green grass grows, then they will eat grass. But some people will still have dried potato peelings and pumpkin peels, which they will grind and cook into cakes that, in a good farm, pigs would not eat. Children preschool age they do not know the color and taste of sugar, sweets, cookies and other confectionery products, but eat potatoes and grass on the same basis as adults.”

The real benefit for the villagers was maturation in summer period berries and mushrooms, which were mainly collected by teenagers for their families.

One workday (a unit of labor accounting on a collective farm) earned by a collective farmer brought him less food than the average city dweller received on a food card. The collective farmer had to work and save all his money for a whole year so that he could buy the cheapest suit.

Empty cabbage soup and porridge

In the cities, things were no better. The country lived in conditions of acute shortages, and in 1946–1947. The country is gripped by a real food crisis. In ordinary stores there was often no food, they looked shabby, and cardboard dummies of food were often displayed in the windows.

Prices at collective farm markets were high: for example, 1 kg of bread cost 150 rubles, which was more than a week’s salary. People stood in lines for flour for several days, the line number was written on their hands with a chemical pencil, and a roll call was held in the morning and evening.

At the same time, commercial stores began to open, where they even sold delicacies and sweets, but they were “unaffordable” for ordinary workers. This is how the American J. Steinbeck, who visited Moscow in 1947, described such a commercial store: “Grocery stores in Moscow are very large, like restaurants, they are divided into two types: those in which products can be purchased with cards, and commercial stores , also run by the government, where you can buy almost simple food, but at very high prices. Canned food is stacked in mountains, champagne and Georgian wines stand in pyramids. We saw products that could be American. There were jars of crab with Japanese brand names on them. There were German products. And here lay the luxurious products of the Soviet Union: large jars of caviar, mountains of sausages from Ukraine, cheeses, fish and even game. And various smoked meats. But these were all delicacies. For a simple Russian, the main thing was how much bread costs and how much it is given, as well as the prices of cabbage and potatoes.”

Rated supplies and commercial trade services could not save people from food difficulties. Most of the townspeople lived from hand to mouth.

The cards provided bread and once a month two bottles (0.5 liters) of vodka. People took it to suburban villages and exchanged it for potatoes. The dream of a person at that time was sauerkraut with potatoes and bread and porridge (mainly pearl barley, millet and oats). Soviet people at that time practically did not see sugar and real tea, not to mention confectionery. Instead of sugar, slices of boiled beets were used, which were dried in the oven. We also drank carrot tea (from dried carrots).

Letters from post-war workers testify to the same thing: city residents were content with empty cabbage soup and porridge amid an acute shortage of bread. This is what they wrote in 1945–1946: “If it weren’t for bread, I would have ended my existence. I live on the same water. In the dining room, you don’t see anything except rotten cabbage and the same fish; the portions are such that you eat and won’t notice whether you had lunch or not” (metallurgical plant worker I.G. Savenkov);

“The food has become worse than during the war - a bowl of gruel and two spoons of oatmeal, and this is for an adult per day” (automobile plant worker M. Pugin).

Currency reform and abolition of cards

The post-war period was marked by two the most important events in the country, which could not but influence daily life people: monetary reform and abolition of cards in 1947

There were two points of view on the abolition of cards. Some believed that this would lead to a flourishing of speculative trade and a worsening food crisis. Others believed that abolishing rationing and allowing commercial trade in bread and cereals would stabilize the food problem.

The card system was abolished. Queues in stores continued to stand, despite a significant increase in prices. The price for 1 kg of black bread increased from 1 rub. up to 3 rub. 40 kopecks, 1 kg of sugar - from 5 rubles. up to 15 rub. 50 kopecks To survive in these conditions, people began to sell things they had acquired before the war.

The markets were in the hands of speculators who sold essential goods: bread, sugar, butter, matches and soap. They were supplied by “unscrupulous” employees of warehouses, bases, shops, and canteens who were in charge of food and supplies. To stop speculation, the Council of Ministers of the USSR in December 1947 issued a decree “On standards for the sale of industrial and food products into one hand.”

The following were sold to one person: bread - 2 kg, cereals and pasta - 1 kg, meat and meat products - 1 kg, sausages and smoked meats - 0.5 kg, sour cream - 0.5 kg, milk - 1 liter, sugar - 0.5 kg, cotton fabrics - 6 m, threads on spools - 1 piece, stockings or socks - 2 pairs, leather, textile or rubber shoes - 1 pair, laundry soap - 1 piece, matches - 2 boxes, kerosene - 2 liters.

The meaning of the monetary reform was explained in his memoirs by the then Minister of Finance A.G. Zverev: “From December 16, 1947, new money was put into circulation and cash began to be exchanged for it, with the exception of small change, within a week (in remote areas - within two weeks) at a ratio of 1 to 10. Deposits and current accounts in savings banks were revalued in the ratio 1 for 1 to 3 thousand rubles, 2 for 3 from 3 thousand to 10 thousand rubles, 1 for 2 over 10 thousand rubles, 4 for 5 for cooperatives and collective farms. All regular old bonds, except for the 1947 loans, were exchanged for bonds of a new loan at 1 for 3 of the old ones, and 3 percent winning bonds at the rate of 1 for 5.”

The monetary reform was carried out at the expense of the people. The money “in the box” suddenly depreciated, the tiny savings of the population were confiscated. If we consider that 15% of savings were kept in savings banks, and 85% were in hand, then it is clear who suffered from the reform. In addition, the reform did not affect the wages of workers and employees, which were kept at the same amount.

Apparently it was done on the Rossiya TV channel for citizens documentary"Life in the USSR after the war" in color. And the voice-over text is read by Lev Durov. And what was life like in the USSR after the war?

(From the very first frames we are given to understand that we're talking about about 1946. What is clearly reflected on the banner “Glory to the CPSU”)

After the war, life in the USSR was a nightmare ( the fact that we are talking about 1946 is also clear from the GAZ-69 car)

Only factories, factories, government agencies and, with rare exceptions, residential buildings were stone buildings.

There was nothing to wear. Soviet women didn’t even know what tights and leggings were. And that’s why they wore men’s trousers under flannel trousers in the cold. ( Women in bloomers are clearly visible in the footage)

(I wonder why women in the USSR needed tights if the need for them appeared (including abroad) during the fashion for miniskirts, i.e. already in the 60s.

By the way, is actor Durov aware that tights according to GOST in the USSR were called stocking leggings?)

(And to confirm that the screen is still 1946, we are shown GZA-651, the production of which began in 1949.)

And ordinary residents wrote letters to the government of something like this: “It’s impossible to live, even if you lie down and die.”

Going back a year, Lev Durov recalls the parade of athletes in 1945. Parade participants lived in barracks and were trained to the point of exhaustion

The parade was held for the leader ( Here he is, Stalin, smiling predatorily)

Cards were abolished in 1947. But there wasn’t much excitement in the stores

Meanwhile, there were no essential goods - salt, matches, flour, eggs. They were sold through the back doors of stores, for which huge queues immediately accumulated, and in order not to miss it or to prevent someone else from getting through, they wrote numbers on their hands ( Here it is - the queue. And the man at the table military uniform, for sure, writes numbers on the hands of citizens)

Once a year, before the May holidays, people rushed to sign up for a government loan for a month's salary.

Therefore, I had to work for free for a month. Those who had no money signed up for half a loan

Those who moved into new apartments had a hard time

In the new areas there was no infrastructure - bakeries, transport, etc.

But the Syuzpechat stalls and tobacco kiosks opened immediately

There were practically no cars on the streets, much less traffic jams

(Based on the footage, one can understand that people sometimes rested, but actor Durov says nothing about this)

The 800th anniversary of Moscow was celebrated on a grand scale

A good place won't be called a camp. Pioneer camp is the place where exhausted parents dumped their children for the summer

(Nothing is said about camp rations in the film.)

(But it tells about the pioneers who grew hemp taller than human height)

In 1954, joint education of children was introduced. This was good - isolated learning led to children becoming enslaved, dumb and withdrawn.

Also in 1954 ( obviously, after the death of the tyrant) people thought about themselves for the first time

Thinking about your appearance

The students looked ahead thoughtfully and dreamed of creating a bright future.

And GUM was opened for Muscovites

There were a lot of products in the stores

But they were incredibly expensive. For example, black caviar cost 141 rubles/kg. And the teacher’s salary was 150 rubles/month

(I wonder why the actor Durov does not say that in reality the teacher had such a salary back in 1932.)

Achievements of the national economy were shown at VDNKh

The women and men in the frame are tense and their faces are stern - this is because these are not real collective farmers, but extras

The scenes in the stores were also done by extras. Moreover, sometimes it was necessary to do several takes

The 1954 physical culture parade, held after Stalin’s death, showed that everything in the country remained the same

Khrushchev, Voroshilov, Saburov, Melenkov, Ulbricht - few people now say anything to these names

And yet, light began to appear in people’s faces

And in 1957 something unprecedented happened - the World Youth Festival

This is what a worker's lunch looked like around that time.

And the thaw made it possible for Soviet people to feel like human beings

U Great Victory there was also a Great Price. The war claimed 27 million. human lives. The country's economy, especially in the territory subject to occupation, was thoroughly undermined: 1,710 cities and towns, more than 70 thousand villages, about 32 thousand industrial enterprises, 65 thousand km of railway lines were completely or partially destroyed, 75 million people lost their homes. The concentration of efforts on military production, necessary to achieve victory, led to a significant depletion of the population's resources and to a decrease in the production of consumer goods. During the war, the previously insignificant housing construction fell sharply, while the country's housing stock was partially destroyed. Later, unfavorable economic and social factors came into play: low wages, an acute housing crisis, the involvement of an increasing number of women in production, etc.

After the war, the birth rate began to decline. In the 50s it was 25 (per 1000), and before the war it was 31. In 1971-1972, per 1000 women aged 15-49 years there were half as many children born per year than in 1938-1939 . In the first post-war years, the working age population of the USSR was also significantly lower than the pre-war one. There is information at the beginning of 1950 in the USSR there were 178.5 million people, that is, 15.6 million less than there were in 1930 - 194.1 million people. In the 60s there was an even greater decline.

The fall in fertility in the first post-war years was associated with the death of entire age groups of men. The death of a significant part of the country's male population during the war created a difficult, often catastrophic situation for millions of families. A large category of widowed families and single mothers has emerged. The woman has double responsibilities: material support families and care for the family itself and the upbringing of children. Although the state took upon itself, especially in large industrial centers, part of the care of children, creating a network of nurseries and kindergartens, they were not enough. To some extent, the institution of “grandmothers” saved me.

The difficulties of the first post-war years were compounded by the enormous damage suffered by agriculture during the war. The occupiers destroyed 98 thousand collective farms and 1876 state farms, took away and slaughtered many millions of heads of livestock, and almost completely deprived the rural areas of the occupied areas of draft power. In agricultural areas, the number of able-bodied people decreased by almost one third. The depletion of human resources in the countryside was also the result of the natural process of urban growth. The village lost an average of up to 2 million people per year. Difficult living conditions in the villages forced young people to leave for the cities. Some of the demobilized soldiers settled in cities after the war and did not want to return to agriculture.

During the war, in many regions of the country, significant areas of land belonging to collective farms were transferred to enterprises and cities, or illegally seized by them. In other areas, land became the subject of purchase and sale. Back in 1939, a decree was issued by the Central Committee of the All-Russian Communist Party (6) and the Council of People's Commissars on measures to combat the squandering of collective farm lands. By the beginning of 1947, more than 2,255 thousand cases of land appropriation or use had been discovered, a total of 4.7 million hectares. Between 1947 and May 1949, the use of 5.9 million hectares of collective farm land was additionally revealed. The higher authorities, starting from local and ending with republican ones, brazenly robbed collective farms, collecting from them, under various pretexts, actual rent in kind.

The debt of various organizations to collective farms amounted to 383 million rubles by September 1946.

IN Akmola region In 1949, the Kazakh SGR took from collective farms 1,500 heads of livestock, 3 thousand centners of grain and products worth about 2 million rubles. The robbers, among whom were leading party and Soviet workers, were not brought to justice.

The squandering of collective farm lands and goods belonging to collective farms caused great indignation among collective farmers. For example, at the general meetings of collective farmers in the Tyumen region (Siberia), dedicated to the resolution of September 19, 1946, 90 thousand collective farmers participated, and the activity was unusual: 11 thousand collective farmers spoke. IN Kemerovo region At meetings to elect new boards, 367 chairmen of collective farms, 2,250 board members and 502 chairmen of the audit commissions of the previous composition were nominated. However, the new composition of the boards could not achieve any significant change: public policy remained the same. Therefore, there was no way out of the deadlock.

After the end of the war, the production of tractors, agricultural machinery and equipment was quickly established. But, despite the improvement in the supply of machinery and tractors to agriculture, the strengthening of the material and technical base of state farms and MTS, the situation in agriculture remained catastrophic. The state continued to invest extremely insignificant funds in agriculture - in the post-war five-year plan, only 16% of all allocations for the national economy.

In 1946, only 76% of the sown area was sown compared to 1940. Due to drought and other troubles, the 1946 harvest was lower even compared to the para-war year of 1945. “In fact, in terms of grain production, the country for a long period was at the level it had pre-revolutionary Russia“,” admitted N. S. Khrushchev. In 1910-1914, the gross grain harvest was 4380 million poods, in 1949-1953 - 4942 million poods. Grain yields were lower than those of 1913, despite mechanization, fertilizers, etc.

Grain yield

1913 -- 8.2 centners per hectare

1925-1926 -- 8.5 centners per hectare

1926-1932 -- 7.5 centners per hectare

1933-1937 -- 7.1 centners per hectare

1949-1953 -- 7.7 centners per hectare

Accordingly, there were fewer agricultural products per capita. Taking the pre-collectivization period of 1928-1929 as 100, production in 1913 was 90.3, in 1930-1932 - 86.8, in 1938-1940 - 90.0, in 1950-1953 - 94.0. As can be seen from the table, grain problem worsened, despite a decrease in grain exports (from 1913 to 1938 by 4.5 times), a reduction in the number of livestock and, consequently, in grain consumption. The number of horses decreased from 1928 to 1935 by 25 million heads, which resulted in savings of more than 10 million tons of grain, 10-15% of the gross grain harvest of that time.

In 1916, there were 58.38 million cattle on the territory of Russia; on January 1, 1941, its number decreased to 54.51 million, and in 1951 there were 57.09 million heads, that is, it was still below the level 1916. The number of cows exceeded the 1916 level only in 1955. In general, according to official data, from 1940 to 1952, gross agricultural output increased (in comparable prices) by only 10%!

The plenum of the Central Committee of the All-Union Communist Party of Bolsheviks in February 1947 demanded even greater centralization of agricultural production, effectively depriving collective farms of the right to decide not only how much, but what to sow. Political departments were restored in machine and tractor stations - propaganda was supposed to replace food for the completely starved and impoverished collective farmers. Collective farms were obliged, in addition to fulfilling state deliveries, to fill up the seed funds, set aside part of the harvest in an indivisible fund, and only after that give the collective farmers money for workdays. State supplies were still planned from the center, harvest prospects were determined by eye, and the actual harvest was often much lower than planned. The first commandment of the collective farmers, “give first to the state,” had to be fulfilled in any way. Local party and Soviet organizations often forced the more successful collective farms to pay in grain and other products for their impoverished neighbors, which ultimately led to the impoverishment of both. Collective farmers fed themselves mainly from food grown on their dwarf plots. But in order to export their products to the market, they needed a special certificate certifying that they had paid for mandatory government supplies. Otherwise, they were considered deserters and speculators, and were subject to fines and even imprisonment. Taxes on personal plots of collective farmers have increased. Collective farmers were required to supply products in kind, which they often did not produce. Therefore, they were forced to purchase these products at market prices and hand them over to the state for free. The Russian village did not know such a terrible state even during the time of the Tatar yoke.

In 1947, a significant part of the country's European territory suffered famine. It arose after a severe drought that affected the main agricultural breadbaskets of the European part of the USSR: a significant part of Ukraine, Moldova, the Lower Volga region, the central regions of Russia, and Crimea. In previous years, the state completely took away the harvest as part of government supplies, sometimes not even leaving a seed fund. Crop failure occurred in a number of areas that were subject to German occupation, that is, they were robbed many times by both strangers and their own. As a result, there were no food supplies to survive hard time. The Soviet state demanded more and more millions of pounds of grain from the completely robbed peasants. For example, in 1946, a year of severe drought, Ukrainian collective farmers owed the state 400 million poods (7.2 million tons) of grain. This figure, and most other planned targets, were set arbitrarily and did not in any way correlate with the actual capabilities of Ukrainian agriculture.

Desperate peasants sent letters to the Ukrainian government in Kyiv and the allied government in Moscow, begging them to come to their aid and save them from starvation. Khrushchev, who was at that time the first secretary of the Central Committee of the CP(b)U, after long and painful hesitation (he was afraid of being accused of sabotage and losing his place), nevertheless sent a letter to Stalin, in which he asked for permission to temporarily introduce card system and conserve food to supply agricultural populations. Stalin, in a reply telegram, rudely rejected the request of the Ukrainian government. Now the Ukrainian peasants faced hunger and death. People began to die in the thousands. Cases of cannibalism appeared. Khrushchev cites in his memoirs a letter to him from the secretary of the Odessa Regional Party Committee A.I. Kirichenko, who visited one of the collective farms in the winter of 1946-1947. This is what he reported: “I saw a terrible scene. The woman put the corpse of her own child on the table and cut it into pieces. She spoke madly as she did this: “We have already eaten Manechka. Now we will salt Vanichka. This will support us for a while.” "Can you imagine this? A woman went crazy because of hunger and cut her own children into pieces! Famine raged in Ukraine.

However, Stalin and his closest assistants did not want to reckon with the facts. The merciless Kaganovich was sent to Ukraine as the first secretary of the Central Committee of the Communist Party (b)U, and Khrushchev temporarily fell out of favor and was transferred to the post of Chairman of the Council of People's Commissars of Ukraine. But no movement could save the situation: the famine continued, and it claimed about a million human lives.

In 1952, government prices for grain, meat, and pork supplies were lower than in 1940. Prices paid for potatoes were lower than transportation costs. Collective farms were paid an average of 8 rubles 63 kopecks per hundredweight of grain. State farms received 29 rubles 70 kopecks per hundredweight.

In order to buy a kilogram of butter, a collective farmer had to work... 60 workdays, and to buy a very modest suit, he needed a year's earnings.

Most collective and state farms in the country in the early 50s harvested extremely low harvests. Even in such fertile regions of Russia as the Central Black Earth Region, the Volga region and Kazakhstan, harvests remained extremely low, because the center endlessly prescribed what to sow and how to sow. The matter, however, was not only about stupid orders from above and insufficient material and technical base. For many years, the peasants were beaten out of love for their work, for the land. Once upon a time, the land rewarded the labor expended, for their dedication to their peasant work, sometimes generously, sometimes meagerly. Now this incentive, officially called the “material interest incentive,” has disappeared. Work on the land turned into free or low-income forced labor.

Many collective farmers were starving, others were systematically malnourished. Household plots were saved. The situation was especially difficult in the European part of the USSR. The situation was much better in Central Asia, where there were high procurement prices for cotton, the main agricultural crop, and in the south, which specialized in vegetable growing, fruit production and winemaking.

In 1950, the consolidation of collective farms began. Their number decreased from 237 thousand to 93 thousand in 1953. The consolidation of collective farms could contribute to their economic strengthening. However, insufficient capital investments, mandatory deliveries and low procurement prices, the lack of a sufficient number of trained specialists and machine operators, and, finally, the restrictions imposed by the state on personal plots of collective farmers deprived them of incentive to work and destroyed hopes of escaping the grip of need. 33 million collective farmers, who fed the country's 200 million population with their hard work, remained, after the prisoners, the poorest, most offended layer of Soviet society.

Let us now see what the position of the working class and other urban sections of the population was at this time.

As is known, one of the first acts of the Provisional Government after February Revolution was the introduction of an 8-hour working day. Before this, Russian workers worked 10 and sometimes 12 hours a day. As for collective farmers, their working day, as in the pre-revolutionary years, remained irregular. In 1940 they returned to 8 o'clock.

According to official Soviet statistics, the average wage of a Soviet worker increased more than 11-fold between the beginning of industrialization (1928) and the end of the Stalin era (1954). But this does not give an idea of real wages. Soviet sources give fantastic calculations that have nothing to do with reality. Western researchers have calculated that during this period, the cost of living, according to the most conservative estimates, increased 9-10 times in the period 1928-1954. However, a worker in the Soviet Union has, in addition to the official salary received in person, an additional one in the form of social services provided to him by the state. It returns to workers in the form of free medical care, education and other things part of the earnings alienated by the state.

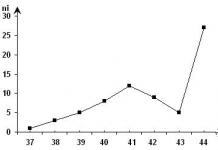

According to the calculations of the largest American specialist on the Soviet economy, Janet Chapman, additional increases in wages of workers and employees, taking into account changes in prices, after 1927 were: in 1928 - 15% in 1937 - 22.1%; in 194O - 20.7%; in 1948 - 29.6%; in 1952 - 22.2%; 1954 - 21.5%. The cost of living in the same years grew as follows, taking 1928 as 100:

From this table it is clear that the increase in wages of Soviet workers and employees was lower than the increase in the cost of living. For example, by 1948, wages in monetary terms had doubled since 1937, but the cost of living had more than tripled. The fall in real wages was also associated with an increase in the amount of loan subscriptions and taxation. The significant increase in real wages by 1952 was still below the level of 1928, although it exceeded the level of real wages in the pre-war years of 1937 and 1940.

To get a correct idea of the situation of the Soviet worker in comparison with his foreign colleagues, let us compare how many products could be bought for 1 hour of work expended. Taking the initial data of the hourly wage of a Soviet worker as 100, we obtain the following comparative table:

The picture is striking: for the same time spent, an English worker could purchase more than 3.5 times more products in 1952, and an American worker could purchase 5.6 times more products than a Soviet worker.

Among Soviet people, especially the older generations, the opinion has taken root that under Stalin prices were reduced every year, and under Khrushchev and after him prices were constantly rising. Hence, there is even some nostalgia for Stalin’s times

The secret of lowering prices is extremely simple - it is based, firstly, on the huge rise in prices after the start of collectivization. In fact, if we take 1937 prices as 100, it turns out that yen for baked rye bread increased 10.5 times from 1928 to 1937, and by 1952 almost 19 times. Prices for first grade beef increased from 1928 to 1937 by 15.7, and by 1952 - by 17 times: for pork, by 10.5 and 20.5 times, respectively. The price of herring increased by almost 15 times by 1952. The cost of sugar rose 6 times by 1937, and 15 times by 1952. The price of sunflower oil rose 28 times from 1928 to 1937, and 34 times from 1928 to 1952. Prices for eggs increased from 1928 to 1937 by 11.3 times, and by 1952 by 19.3 times. And finally, potato prices rose 5 times from 1928 to 1937, and in 1952 they were 11 times higher than the 1928 price level

All this data is taken from Soviet price tags for different years.

Having once raised prices by 1500-2500 percent, then it was quite easy to organize a trick with annual price reductions. Secondly, the reduction in prices occurred due to the robbery of collective farmers, that is, extremely low state delivery and purchase prices. Back in 1953, procurement prices for potatoes in the Moscow and Leningrad regions were equal to ... 2.5 - 3 kopecks per kilogram. Finally, the majority of the population did not feel any difference in prices at all, since government supplies were very poor; in many areas, meat, fats and other products were not delivered to stores for years.

This is the “secret” of the annual price reduction during Stalin’s times.

A worker in the USSR, 25 years after the revolution, continued to eat worse than a Western worker.

The housing crisis has worsened. Compared to pre-revolutionary times, when the housing problem in densely populated cities was not easy (1913 - 7 square meters per person), in the post-revolutionary years, especially during the period of collectivization, the housing problem became unusually worse. Masses of rural residents poured into the cities, seeking relief from hunger or in search of work. Civil housing construction was unusually limited during Stalin's times. Apartments in the cities were given to senior officials of the party and state apparatus. In Moscow, for example, in the early 30s, a huge residential complex was built on Bersenevskaya Embankment - the Government House with large comfortable apartments. A few hundred meters from the Government House there is another residential complex - a former almshouse, converted into communal apartments, where there was one kitchen and 1-2 toilets for 20-30 people.

Before the revolution, most workers lived near the enterprises in barracks; after the revolution, the barracks were called dormitories. Large enterprises built new dormitories for their workers, apartments for engineering, technical and administrative staff, but it was still impossible to solve the housing problem, since the lion's share of funds was spent on the development of industry, the military industry, and the energy system.

Housing conditions for the vast majority of the urban population worsened every year during Stalin's reign: the rate of population growth significantly exceeded the rate of civil housing construction.

In 1928, the housing area per city resident was 5.8 square meters. meters, in 1932 4.9 square meters. meters, in 1937 - 4.6 square meters. meters.

The 1st Five-Year Plan provided for the construction of new 62.5 million square meters. meters of living space, but only 23.5 million square meters were built. meters. According to the 2nd five-year plan, it was planned to build 72.5 million square meters. meters, 2.8 times less than 26.8 million square meters were built. meters.

In 1940, the living space per city resident was 4.5 square meters. meters.

Two years after Stalin's death, when mass housing construction began, there was 5.1 square meters per city resident. meters. In order to realize how crowded people lived, it should be mentioned that even the official Soviet housing standard is 9 square meters. meters per person (in Czechoslovakia - 17 sq. meters). Many families huddled in an area of 6 square meters. meters. They lived not in families, but in clans - two or three generations in one room.

The family of a cleaning lady at a large Moscow enterprise in the 13th century A-voy lived in a dormitory in a room with an area of 20 square meters. meters. The cleaner herself was the widow of the commandant of the border outpost who died at the beginning of the German-Soviet war. There were only seven fixed beds in the room. The remaining six people - adults and children - lay out on the floor for the night. Sexual relations took place almost in plain sight; people got used to it and didn’t pay attention to it. For 15 years, the three families living in the room unsuccessfully sought relocation. Only in the early 60s were they resettled.

Hundreds of thousands, if not millions, of residents of the Soviet Union lived in such conditions in the post-war period. This was the legacy of the Stalin era.